GREEK TRAGIC DRAMA The birthplace of tragedy was the city of

advertisement

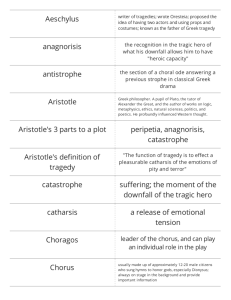

GREEK TRAGIC DRAMA The birthplace of tragedy was the city of Athens, and here it also reached its full flower in the fifth century B.C. in the masterpieces of the three great Greek tragedians: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. Greek tragic drama–and tragedy as a genre–evolved from primitive elements. Basic was the cult of Dionysus (Bacchus), a young god whose worship began to spread into Greece from the north about 700 B.C. Dionysus was not merely the god of wine, but of the generative forces in nature. Tragedy evolved from the choral lyric poem in honor of Dionysus, sung and danced around an altar of Dionysus in circular dancing place (the Greek word for “dancing place” is orchestra). This choral song was performed by a chorus of fifty men disguised in skins of goats, sacred animals of the god Dionysus. Thus we have the term tragoedia, which means “goat song.” The chorus represented satyrs, woodland companions of Dionysus, and they sang a hymn to the god. THESPIS ACTORS About the middle of the sixth century B.C., an Athenian by the name of Thespis (c. 550-500 B.C.) introduced the first actor, the Greek word for which ishypokrites–literally, “answerer.” Accordingly, Thespis is known as the father of drama, and modern actors are sometimes called Thespians after him. The new single actor added by Thespis was separate from the leader of the chorus. This actor impersonated various characters and delivered monologues(solitary speeches) or conducted dialogues (conversations) with the leader of the chorus. He performed at intervals between the dances of the chorus of satyrs, changing costumes several times and taking several roles during the performance. Thus was drama–literally, “action”—born. Soon, because of the plot limitations of the legends of Dionysus, myths not connected with Dionysus were introduced, probably first by Thespis. With this development, it became necessary to alter the original chorus of satyrs, so that in each new play a chorus of persons appropriate to the plot was employed. In 534 B.C. Peisistratus, tyrant of Athens, gave official recognition to tragedy in the state cult of Athens, instituting a new festival, the City Dionysia, with a contest in tragedy as the principal feature. The first writer to raise tragedy to the rank of real literature was Aeschylus. He added a second actor and thus made tragedy truly dramatic. This innovation at once enlarged the scope of the action, made possible true dialogue apart from conversation with the chorus, and allowed visualization of tragic conflict. Each of the two actors could take several parts so that the complexity of the plot increased. As a result, the importance of the chorus was diminished. Sophocles, the author of Oedipus the King, raised the number of actors to three and limited the number of the chorus to fifteen. This new literary form–Greek tragic drama–was developed, then, from myths, mostly derived from the Homeric epics and related sources; from choral odes, derived from primitive songs to Dionysus; and from the AUDIENCE DIONYSIA DRAMATIC tetralogy. This COMPETITION MASKS dialogue of the actors. A Greek tragedy was a musical tragedy, similar to a Wagnerian opera. The theater was a public institution, and plays were produced by the state as an annual ritual of the state religion in a public theater. Plays could be seen only on specific occasions, when festivals of Dionysus were celebrated. Classical Greek drama was a community art, not a business venture, with an audience that consisted of the mass of Athenian citizens; women, boys, even slaves, were admitted. The function of the dramatists in Athenian society was of highest importance. They were regarded as teachers of the people who presented their plays for the ethical, moral, and political improvement of their fellow citizens. The Great (or City) Dionysia was celebrated for five days at the beginning of the spring, from the end of March into early April. On the first day of the festival there was a grand procession of the entire citizenry in honor of Dionysus. His statue was carried through the city to the theater of Dionysus in a magnificent spectacle. On the second day five choral lyrics by men and five choral lyrics by boys were performed. On each of the last three days, three tragedies and one satyr play by a poet selected for the occasion were performed. This was followed each day by one comedy. Each tragic poet offered a group of four plays, called a consisted of a trilogy–three tragedies, at first on one unified theme, later on separate subjects, followed by a satyr play, mockheroic tragicomedy, which became part of the official ritual about 500 B.C. The satyr play was on a Dionysiac theme and was a concession to religious conservatism, so that the association with the god Dionysus would not be forgotten. It also served as a relief from the tension of the three severe tragedies. At the end of the Dionysia, prizes were awarded to the victorious poet by juries of citizens who were selected by lot to choose the victors. The prizes were among the highest honors that could be bestowed upon an Athenian by his fellow citizens. Errors in judgment were inevitable (for instance, theOedipus the King of Sophocles, regarded today as one of the great dramas in world literature, did not win first prize), but the large number of victories of Aeschylus and Sophocles is a tribute to the fairness and competence of the judges. Originally, in a Greek dramatic production, the poet was not only author but also producer, choreographer, and chief actor, playing the leading roles in each play. All actors wore masks appropriate to the part. Hence the term dramatis personnae, a Latin expression that means, literally, “the masks of the drama.” The mask, of religious origin, identified the character for the audience in the vast theaters of antiquity. It also served as a sort of speaking tube to amplify the voice. But it had the disadvantage of preventing the portrayal of nuances of emotion through facial expression. This had to be accomplished, therefore, by the voice and by gestures. The masks, usually made of linen, had a protuberance above the forehead to give added stature to the actor and impressiveness to the face; for the characters portrayed in Greek drama were almost always gods and heroes. The chorus also wore masks and was present throughout the action of the play, after its entrance. This fact imposes an unrealistic feature on Greek tragedy that creates many technical problems. For example, the ever-present chorus is aware of all secrets and intrigues of the characters. Moreover, their presence tends to limit the action to places where a group such as they represent may be expected to congregate. Their presence also tends to concentrate the action into a short period of time. ROLE OF CHORUS The lyric odes of the chorus, often of extraordinary beauty, were sung and danced at intervals in the play. The chorus often set the mood of the play, interpreted the events, and generalized the meaning of the action, expounding the central themes of the play. The chorus has been called the ideal spectator, bridging the gap between the players and the audience. The chorus occasionally served to relieve tension, or to give the background of events affecting the action of the drama. Moreover, it had a dual character, as narrator and as an actor, for it often conversed with and gave advice to the characters. The leader of the chorus (choryphæus) had a special importance, acting as spokesman for the group. The choral odes are divided into strophe (“movement”), antistrophe(“countermovement”), and epode (“afterpiece”). These were originally choreographic notations. Occasionally, chorus and actors engage in a kommos, a responsive lyric exchange. FORM OF DRAMA A typical Greek tragedy had a conventional structure, which, it will be seen, highlights its origin in a choral lyric. The play opened with a prologue, by definition, the action before the entrance of the chorus. Then came the parados, the entering lyric of the chorus. This was followed by the alternatingepisodes, performed by the actors, and the stasima, choral odes. The play ended with the exodos, the action after the last stasimon. CONSTRUCTION OF Greek theaters were always open-air, built on the slope of a hill. The THEATER audience sat in the theatron (“seeing place”) on tiers of seats on a hollowedout hillside. There were usually seats of honor for public officials and priests, with the principal seat reserved for the priest of Dionysus. At Athens, in the Theater of Dionysus on the site of the Acropolis, there were sixty-seven seats of honor for the principal civil and religious dignitaries and for distinguished foreign visitors. In the fifth century B.C., the Theater of Dionysus had wooden seats. Most of the stone remains of the extant theater are from the reconstruction made in the fourth century B.C. by Lycurgus, finance minister of Athens (338-326 B.C.). The seating capacity was about seventeen thousand. All the action and dancing of the chorus took place in the circular orchestra (“dancing place”) at the foot of the theatron. It is believed by modern scholars that a raised stage existed in the Greek UNITIES DRAMATIC IRONY theater of classical times. But the actors performed on three levels: in the orchestra, on the stage, and on the roof of the skene. In the center of the orchestra was the altar of Dionysus (the thymele), where sacrifices were performed to the god before the plays were given. The skene (literally, “tent” or “hut”) served as the dressing room of the actors. The façade of the building, the proscenium, carried the scenery of the play, which was simple and conventional, and usually represented the front of a palace or a temple with three doorways, presenting an imposing building with columns, pediments, and statues. There was no stage curtain in the Greek theater. By the middle of the fifth century B.C., painted scenery, attributed to Sophocles, was fully established. Scenery consisted of painted draperies or boards attached to the wall of the skene. Changes of scenery in the course of a play were almost unknown in the classical period. The skene was flanked on either side by a parascenium (“wing”). Between the theatron and the skene, at each side, was aparados, the point of entry and exit of the chorus. Since it was a ceremony of the state religion and was supervised by state officials, classical Greek drama tended to develop rules and conventions that hampered free experimentation. There were severe limitations on changes of scenery, and the scene of the drama was always outdoors. Lighting effects were impossible: all scenes (even night scenes) were acted in broad daylight. Interior scenes or events that took place away from the scene of the action could not be shown. These were communicated to the audience in a narration by a messenger or in dramatic exposition. There was neither curtain not intermission. Because of the religious associations of the theater and other technical limitations, no violence was permitted to be portrayed before the audience, although suicide was apparently an exception to this rule. Greek tragedians practiced that is called unity of action. This involved concentration on a single action, with no irrelevancies or subplots employed. Unity of time (that is, limitation of the action to a time period not exceeding twenty-four hours) and unity of place (one unchanged scene throughout the play), though frequently found in Greek plays, were not formal conventions in the fifth century B.C. The unities of time and place were matters of stage convenience and theatrical necessity resulting from the continuous presence of the chorus. Greek plays were thus distinguished by a simplicity and an intense concentration, unlike the sprawling discursiveness of a Shakespearean play. This concentration and simplicity were enhanced by the tendency to maintain economy in number of roles. Another peculiarity of fifth century B.C. Athenian drama is noteworthy: each dramatic festival presented original works in single performances, and these plays were usually never again performed, although they might, of course, also be given at the Rural Dionysia. There was little suspense for the audience in viewing a Greek tragedy: the general outline of the plots were known in advance because the poets selected the stories almost exclusively from well-known myths. The principal interest of the audience, apart from participation in a religious festival, was in the religious and ethical instruction conveyed by the plays, in the skill of the actors and the chorus, in the beauty of the spectacle as a whole, and in the pleasurable appreciation of dramatic irony. The latter was, indeed, one of the most characteristic features of Greek tragedy. Dramatic irony involves double meaning in what is said and done, because the audience, which had foreknowledge of the plot, understands words and events in a different way from the characters. From http://faculty.musowls.org/Sheltont/Literature/HO(gtd).htm