Providing Lifelong Nutrition Skills to Pregnant Adolescents

advertisement

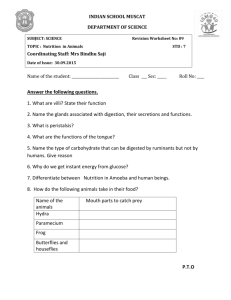

Providing Lifelong Nutrition Skills to Pregnant Adolescents Carrielyn Rhea, BSN RN | FNP/PHL Program at UVA | GNUR 8610 Abstract • The United States has the highest adolescent pregnancy rate in the developed world • Every 31 seconds an adolescent becomes pregnant in the United States • Current research shows that nutrition during adolescent pregnancy is directly associated with the outcome of the infant at delivery Abstract – 2 • Many programs exist to provide nutrition counseling and nutrition resources to pregnant adolescents • Expansion is needed on how to shop and select nutritionally sound foods and how to prepare them • 1 on 1 time with a nutrition counselor to individualize program • Taking small groups into a grocery store to shop • Providing basic storage and cooking classes Nutrition & Adolescent Pregnancy • Adolescents: 12-18 years of age • Pregnancy in the adolescent years is a time of great nutritional risk • Adolescents who are at greater risk for becoming pregnant, are often more likely to have inadequate nutrition • Adolescents have a higher rate of: • • • low birth-weight infants preterm labor infant mortality • These risks can be reduced by proper nutrition during pregnancy Literature Summary Research Studies 1. Nutritional needs of pregnant adolescents are greater than those of adult women (Frisancho et al., 1983; Scholl et al., 1990) 2. Increased needs compete with the needs of the developing fetus (Frisancho et al., 1983; Scholl et al., 1990) 3. Weight gain during pregnancy is directly associated with infant birth weight and infant mortality (Hediger et al., 1990) 4. Intake of macro and micro nutrients is directly associated with infant birth weight and preterm labor (Scholl et al., 1991; Baker et al., 2009) 5. Diet’s low in protein, fat, and energy are associated with less subcutaneous fat. Children born to mothers with less subcutaneous fat are more likely to develop hypertension later in life (Adair et al., 2001) Literature Summary Gaps in Knowledge • Specific recommendations were not made for: • Amount of weight gain needed • Amount of macro nutrients (fat, protein, and carbohydrates) • Amount of micro nutrients (vitamins, minerals, and nutrients) Literature Summary Current Programs These programs provide nutrition counseling and nutrition resources to pregnant adolescents • National – Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) – Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) • Local – Teen Parent Programs – Pregnancy Help Centers Literature Summary Gaps in Current Programs • Many adolescents do not know how to: • • • • Select good produce and meat in a grocery store Read a food label Store food Prepare and cook nutritionally sound meals • Current programs do not teach these skills PROJECT OBJECTIVE: Comprehensive program that will provide pregnant adolescents with the knowledge and skills necessary for lifelong nutrition for both her and her child Health Belief Model • This model looks at an individual’s motivation to engage in a health promoting behavior by understanding that person’s: • • • • • • Perceived susceptibility Perceived severity Perceived benefits Perceived barriers Cues to action Self-efficacy (Edberg, 2007) Applying the Model • Brochure to highlight: • Nutrition risks of pregnant adolescents • Statistics of positive outcomes from good maternal nutrition • Statistics of negative outcomes from poor maternal nutrition • Highlights of the proposed program and how it will benefit them Applying the Model – 2 • Brochure will help pregnant adolescents to see their: • Susceptibility to poor outcomes • Consequences if they do not eat properly • Benefits if they do eat properly • Overcome barriers to resources • Motivate them to seek action Applying the Model – 3 • Brochure to be placed in: • Pregnancy Help Centers • Local Obstetrician’s offices • School nurse’s offices/school wellness centers Implementation Plan Once pregnant adolescents are referred and/or choose to enroll in the program, they will be empowered to obtain self-efficacy by: • Having weekly nutrition classes as a group • Meeting 1 on 1 with a nutrition counselor initially and then once a month to determine their body mass index (BMI), goal for weight gain, and to monitor that weight gain Implementation Plan – 2 • Being encouraged to enroll in WIC in order to receive food stamps and food resources • Going grocery shopping with a nutrition counselor in groups of 2-3 to have hands-on practice with: • Selecting good produce and meat • Reading nutrition labels • Making healthy selections while maintaining a budget • Having basic food storage and cooking lessons from nutrition counselor “Nutrition Counselor” • A nutrition counselor may be a: • Nutritionist • Nurse practitioner • Other health care professional with an interest in and the training necessary to be a nutrition counselor Innovation • Specifically addresses the nutrition needs of pregnant adolescents • Individualizes plan for each pregnant adolescent • Utilizes multiple learning modalities to increase student comprehension: • Hands-on learning • Classroom instruction • 1 on 1 instruction Innovation – 2 • Provides skills necessary for lifelong nutrition • Is a comprehensive program that takes nutrition and food consumption from start to finish • Empowers pregnant adolescents to obtain self-efficacy as in the HBM Innovation – 3 Knowledge (what to eat and how much) Financial Resources (to pay for food) Selecting & Purchasing Food Preparing, Consuming, & Storing Food Evaluation • Participants will be evaluated by: • Weight gain throughout pregnancy • Return demonstrations of learned skills • Food diaries • Program will be evaluated by: • Outcome of newborns at delivery compared with the national average of newborns born to mothers of the same age • Course evaluations submitted by the students both during and after the completion of the program Budget Estimate • Expenses to include: • Project manager salary • Nutrition counselor’s pay (based on having 5 students to begin, 14 hours per week) • Classroom materials • Materials to print brochures • Training funds • Funds for food used during cooking classes • Public transportation for students to get to grocery store if needed References – 1 • Adair, L.S., Kuzawa, C.W., & Borja, J. (2001). Maternal energy stores and diet composition during pregnancy program adolescent blood pressure. Circulation: Journal of the American Heart Association, 104, 1034-1039. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.095037. • Baker, P.N., Wheeler, S.J. Sanders, T.A., Thomas, J.E., Hutchinson, C.J., Clarke, K., Berry, J.L., Jones, R.L., Seed, P.T. & Poston, L. (2009). A prospective study of micronutrient status in adolescent pregnancy. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 89, 1114-1124. • Dubois, S., Coulombe, C., Pencharz, P., Pinsonneault, O., & Duquette, M. (1997). Ability of the Higgins nutrition intervention program to improve adolescent pregnancy outcome. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 97 (8), 871-878. • Edberg, M. (2007). Essentials of health behavior: Social and behavioral theory in public health. Boston, MA: Jones and Bartlett. References – 2 • Frisancho, A.R., Matos, J. & Flegel, P. (1983). Maternal nutritional status and adolescent pregnancy outcome. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 38, 739-746. • Hediger, M.L., Scholl, T.O., Ances, I.G., Beisky, D.H., & Wexberg Salmon, R. (1990). Rate and amount of weight gain during adolescent pregnancy: associations with maternal weight-for-height and birth weight. American Society for Clinical Nutrition, 52, 793799. • Lenders, C.M., McElrath, T.F., & Scholl, T.O. (2000). Nutrition in adolescent pregnancy. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 12 (3), 291296. • Pregnant and parenting adolescents. (2011). North Carolina Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program website. Retrieved from: http://www.ces.ncsu.edu/ EFNEP/pt.html. References – 3 • Scholl, T.O., Hediger, M.L., Khoo, C., Healey, M.F., & Rawson, N.L. (1991). Maternal weight gain, diet and infant birth weight: correlations during adolescent pregnancy. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 44 (4/5), 423-428. • Scholl, T.O., Hediger, M.L., & Ances, I.G. (1990). Maternal growth during pregnancy and decreased infant birth weight. American Journal for Clinical Nutrition, 51, 790-793. • Stevens-Simon, C. & McAnarney, E.R. (1996). Adolescent pregnancy. In R.J. DiClemente, W.B. Hansen and L.E. Ponton (Eds.) Handbook of Adolescent Health Risk Behavior, (pp. 313-332). New York: Plenum Press. • Teen parents: nutrition curriculum for pregnant and parenting teens. (2007, February). University of Missouri Extension website. Retrieved from: http://extension.missouri.edu/publications/DisplayPub.aspx?P=N715 References – 4 • Wallace, J., Bourke, D., Da Silva, P., & Aitken, R. (2001). Nutrient partitioning during adolescent pregnancy. Journals of Reproduction and Fertility, 122, 347-357. • Wallace, J.M., Luther, J.S., Milne, J.S., Aitken, R.P., Redmer, D.A., Reynolds, L.P., & Hay, W.W. (2005). Nutritional modulation of adolescent pregnancy outcome: a review. Placenta, 27, S61-S68. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2005.12.002. • WIC factsheet (2010, May 5). Food & Nutrition Service USDA website. Retrieved from: http://www.fns.usda.gov/wic/factsheets.htm