Advanced Thermodynamics

advertisement

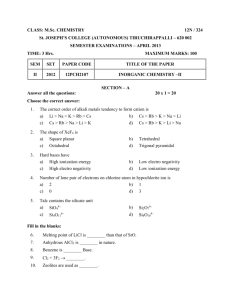

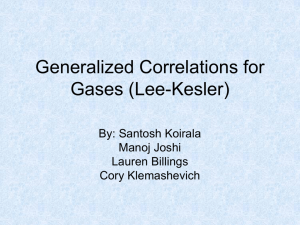

Advanced Thermodynamics Note 2 Volumetric Properties of Pure Fluids Lecturer: 郭修伯 A pressure-temperature diagram • the sublimation curve • the fusion curve • the vaporization curve • the triple point • the critical point Fig 3.1 A pressure-volume diagram • The isotherms – the subcooled-liquid and the superheated-vapor regions – isotherms in the subcooledliquid regions are steep because liquid volumes change little with large change in pressure • The two-phase coexist region • The triple point is the horizontal line • The critical point Fig 3.2 • An equation of state exists relating pressure, molar or specific volume, and temperature for any pure homogeneous fluid in equilibrium states. • An equation of state may be solved for any one of the three quantities P, V, or T as a function of the other two. • Example: V V dV dT dP T P P T 1 V Volume expansivity: V T P 1 V Isothermal compressibility: V P T dV dT dP V – For incompressible fluid, both β andκ are zero. – For liquids β is almost positive (liquid water between 0°C and 4°C is an exception), and κ is necessarily positive. – At conditions not close to the critical point, β andκ can be assumed constant: V2 ln V1 (T2 T1 ) ( P2 P1 ) Virial equations of state • PV along an isotherm: • PV a bP cP 2 a(1 BP CP 2 DP3 ...) – The limiting value of PV as P →0 for all the gases: – PV * a f (T ) – PV * a RT , with R as the proportionally constant. – Assign the value of 273.16 K to the temperature of the triple point of water: PV * R 273.16 • Ideal gas: t – the pressure ~ 0; the molecules are separated by infinite distance; the intermolecular forces approaches zero. – PV *t cm 3 bar R 83.1447 273.16 mol K The virial equations • The compressibility factor: PV Z RT • the virial expansion: Z (1 BP CP 2 DP3 ...) – the parameters B’, C’, D’, etc. are virial coefficients, accounting of interactions between molecules. – the only equation of state proposed for gases having a firm basis in theory. – The methods of statistical mechanics allow derivation of the virial equations and provide physical significance to the virial coefficients. Ideal gas • No interactions between molecules. • gases at pressure up to a few bars may often be considered ideal and simple equations then apply • the internal energy of gas depends on temperature only. – Z = 1; PV = RT – U = U (T) – C U dU C (T ) C H dH dU R C R C (T ) V V P V P T V dT T P dT dT U CV dT H C P dT – Mechanically reversible closed-system process, for a unit mass or a mole: CV CP dQ dW CV dT dQ VdP PdV R R dW PdV • For ideal gas with constant heat capacities undergoing a mechanically reversible adiabatic process: dQ dW CV dT T2 P2 T1 P1 R CP PV const . dW PdV dT R dV T CV V T2 V1 T1 V2 R CV CP CV – for monatomic gases, 1.67 – for diatomic gases, 1.4 – for simple polyatomic gases, such as CO2, SO2, NH3, and CH4, 1.3 • The work of an irreversible process is calculated: – First, the work is determined for a mechanically reversible process. – Second, the result is multiple or divided by an efficiency to give the actual work. Air is compressed from an initial condition of 1 bar and 25°C to a final state of 5 bar and 25 °C by three different mechanically reversible processes in a closed system. (1) heating at constant volume followed by cooling at constant pressure; (2) isothermal compression; (3) adiabatic compression followed by cooling at constant volume. Assume air to be an ideal gas with the constant heat capacities, CV = (5/2)R and CP = (7/2)R. Calculate the work required, heat transferred, and the changes in internal energy and enthalpy of the air in each process. Fig 3.7 Choose the system as 1 mol of air, contained in an imaginary frictionless piston /cylinder arrangement. For R = 8.314 J/mol.K, CV = 20.785, CP = 29.099 J/mol.K The initial and final molar volumes are: V1 = 0.02479 m3 and V2 = 0.004958 m3 The initial and final temperatures are identical: ΔU = ΔH = 0 (1) Q = CVΔT + CPΔT = -9915 J; W = ΔU - Q = 9915 J P1 (2) Q W RT ln 3990 J P2 V1 T T (3) adiabatic compression: 2 1 V2 1 567.57 K W CV T 5600 J cooling at constant V, W = 0. overall, W = 5600 J, Q = ΔU - W = -5600 J. V P2 P1 1 9.52 bar V2 An ideal gas undergoes the following sequence of mechanically reversible processes in a closed system: (1) From an initial state of 70°C and 1 bar, it is compressed adiabatically to 150 °C. (2) It is then cooled from 150 to 70 °C at constant pressure. (3) Finally, it is expanded isothermally to its original state. Calculate W, Q, ΔU, and ΔH for each of the three processes and for the entire cycle. Take CV = (3/2)R and CP = (5/2)R. If these processes are carried out irreversibly but so as to accomplish exactly the same changes of state (i.e. the same changes in P, T, U, and H), then different values of Q and W result. Calculate Q and W if each step is carried out with an efficiency of 80%. Fig 3.8 Choose the system as 1 mol of air, contained in an imaginary frictionless piston /cylinder arrangement. For R = 8.314 J/mol.K, CV = 12.471, CP = 20.785 J/mol.K (1) For an ideal gas undergoing adiabatic compression, Q = 0 ΔU = W = CVΔT = 12.471(150 – 70) = 998 J ΔH = CPΔT = 20.785(150 – 70) = 1663 J T2 ( 1) P2 P1 1.689 bar T1 (2) For the constant-pressure process: Q = ΔH = CPΔT = 20.785(70 – 150) = -1663 J ΔU = CVΔT = 12.471(70 – 150) = -998 J W = ΔU – Q = 665 J (3) Isotherm process, ΔU and ΔH are zero: P3 Q W RT ln 1495 J P1 (4) Overall: Q = 0 – 1663 + 1495 = -168 J W = 998 + 665 – 1495 = 168 J ΔU = 0 ΔH = 0 Irreversible processes: (1) For 80% efficiency: W(irreversible) = W(reversible) / 0.8 = 1248 J ΔU(irreversible) = ΔU(reversible) = 998 J Q(irreversible) = ΔU – W = -250 J (2) For 80% efficiency: W(irreversible) = W(reversible) / 0.8 = 831 J ΔU = CVΔT = 12.471(70 – 150) = -998 J Q = ΔU – W = -998 – 831 = -1829 J (3) Isotherm process, ΔU and ΔH are zero: W(irreversible) = W(reversible) x 0.8 = -1196 J Q = ΔU – W = 1196 J (4) Overall: Q = -250 – 1829 + 1196 = -883 J W = 1248 + 831 – 1196 = 883 J ΔU = 0 ΔH = 0 The total work required when the cycle consists of three irreversible steps is more than 5 times the total work required when the steps are mechanically reversible, even though each irreversible step is assumed 80% efficient. A 400g mass of nitrogen at 27 °C is held in a vertical cylinder by a frictionless piston. The weight of the piston makes the pressure of the nitrogen 0.35 bar higher than that of the surrounding atmosphere, which is at 1 bar and 27°C. Take CV = (5/2)R and CP = (7/2)R. Consider the following sequence of processes: (1) Immersed in an ice/water bath and comes to equilibrium (2) Compressed reversibly at the constant temperature of 0°C until the gas volume reaches one-half the value at the end of step (1) and fixed the piston by latches (3) Removed from the ice/water bath and comes to equilibrium to thermal equilibrium with the surrounding atmosphere (4) Remove the latches and the apparatus return to complete equilibrium with its surroundings. Nitrogen may be considered an ideal gas. Calculate W, Q, ΔU, and ΔH for each step of the cycle. The steps: P (1) 27 C, 1.35bar const 0 C, 1.35bar (2) (3) (4) 1 T 0 C , V2 const 0 C , V3 V2 2 V 0 C , V3 const 27 C , V4 V3 4 T1 27 C, P4 T 27 C, 1.35bar n m 14.286 mol M Fig 3.9 (1) W n PdV nPV nRT 3207 J Q nH nC T 11224 J 1 1 P 1 nU1 Q1 W1 11224 3207 8017 J (2) U H 0 2 2 Q2 W2 nRT ln V3 22487 J V2 (3) W 0 Q nU nC T 8017 J nH nC T 11224 J 3 3 V 3 P 3 (4) the oscillation of the piston U 4 H 4 0 Q4 W4 Air flows at a steady rate through a horizontal insulated pipe which contains a partly closed valve. The conditions of the air upstream from the valve are 20°C and 6 bar, and the downstream pressure is 3 bar. The line leaving the valve is enough larger than the entrance line so that the kinetic-energy change as it flows through the valve is negligible. If air is regarded as an ideal gas, what is the temperature of the air some distance downstream from the valve? Flow through a partly closed valve is known as a throttling process. For steady flow system: d (mU )cv 1 Q W H u 2 zg m dt 2 fs Ideal gas: H C P dT The result that ΔH = 0 is general for a throttling process. H 0 T2 T1 If the flow rate of the air is 1 mol/s and if the pipe has an inner diameter of 5 cm, both upstream and downstream from the valve, what is the kinetic-energy change of the air and what is its temperature change? For air, CP = (7/2)R and the molar mass is M = 29 g/mol. Upstream molar volume: RT1 83.14 293.15 1 V 6 3 m 2 V1 10 4.062 10 u n n 2.069 m 1 mol s P1 6 A A Downstream molar volume: V2 2V1 u2 2u1 4.138 m s The rate of the change in kinetic energy: 2 2 1 2 1 2 3 (4.138 2.069 ) u nM u (1 29 10 ) m 0.186 J s 2 2 2 d (mU )cv 1 Q W H u 2 zg m dt 2 fs C 1 m P T u 2 0 2 M T 0.0064 K Application of the virial equations • Differentiation: Z 2 B 2CP 3DP ... P T Z B P T ; P 0 • the virial equation truncated to two terms satisfactorily represent the PVT behavior up to about 5 bar Z 1 BP Z 1 BP B 1 RT V • the virial equation truncated to three terms provides good results for pressure range above 5 bar but below the critical pressure B C 2 Z 1 2 Z 1 BP C P V V Reported values for the virial coefficients of isopropanol vapor at 200°C are: B = -388 cm3/mol and C = -26000 cm6/mol2. Calculate V and Z for isopropanol vapor at 200 °C and 10 bar by (1) the ideal gas equation; (2) two-term virial equation; (3) three-term virial equation. (1) For an ideal gas, Z = 1: V 3 RT 83.14 473.15 3934 cm mol P 10 (2) two-term virial equation: V 3 RT B 3934 388 3546 cm mol P Z PV 0.9014 RT (3) three-term virial equation: Vi 1 RT P B C 388 26000 cm3 1 2 39341 3539 1st iteration 2 mol 3934 (3934) Vi Vi Ideal gas value ... 3 After 5 iterations V4 ~ V5 3488 cm mol Z PV 0.8866 RT Cubic equations of state • Simple equation capable of representing both liquid and vapor behavior. RT • The van del Waals equation of state: P a V b V 2 – a and b are positive constants – unrealistic behavior in the two-phase region. In reality, two, within the two-phase region, saturated liquid and saturated vapor coexist in varying proportions at the saturation or vapor pressure. – Three volume roots, of which two may be complex. – Physically meaningful values of V are always real, positive, and greater than constant b. Fig 3.12 A generic cubic equation of state • General form: P RT (V ) V b (V b)(V 2 V ) – where b, θ, κ,λ and η are parameters depend on temperature and (mixture) composition. – Reduce to the van der Waals equation when η= b, θ= a, and κ=λ= 0. – Set η= b, θ= a (T), κ= (ε+σ) b, λ = εσb2, we have: P RT a(T ) V b (V b)(V b) • where ε and σ are pure numbers, the same for all substances, whereas a(T) and b are substance dependent. • Determination of the parameters: – horizontal inflection at the critical point: 2P P 2 0 V T ;cr V T ;cr • 5 parameters (Pc, Vc, Tc, a(Tc), b) with 3 equations, one has: 3 RTc Vc 8 Pc Zc 27 R 2Tc2 a 64 Pc b 1 RTc 8 Pc PcVc 3 RTc 8 • • Unfortunately, it does not agree with the experiment. Each chemical species has its own value of Zc. • Similarly, one obtain a and b at different T. RT a(T ) P V b V (V b) a(T ) (Tr ) R 2Tc2 Pc b RTc Pc Two-parameter and three-parameter theorems of corresponding states • Two-parameter theorem: all fluids, when compared at the same reduced temperature and reduced pressure, have approximately the same compressibility factor, and all deviate from ideal-gas behavior to about the same degree. T P • Define reduced temperature and reduced pressure: Tr Pr Tc Pc • Not really enough to describe the state, a third corresponding-states parameter is required. – The most popular such parameter is the acentric factor (K.S. Pitzer, 1995): 1.0 log Prsat T 0.7 r • Three-parameter theorem: all fluids having the same value of ω, when compared at the same reduced temperature and reduced pressure, and all deviate from ideal-gas behavior to about the same degree. • Vapor and vapor-like V q RT a(T ) V b b P P (V b)(V b) a (T ) (Tr ) bRT Tr Z 1 q V starts with V(ideal-gas) and then iteration bP P r RT Tr Z ( Z )( Z ) • Liquid and liquid-like RT bP VP V b (V b)(V b) a(T ) a (T ) (Tr ) bP P q r bRT Tr RT Tr V starts with V = b and then iteration 1 Z Z ( Z )( Z ) q Equations of state which express Z as a function of Tr and Pr are said to be generalized, because of their general applicability of all gases and liquids. 2-parameter/3-parameter E.O.S. • Express Z as functions of Tr and Pr only, yield 2parameter corresponding states correlations: – The van der Waals equation – The Redlich/Kwong equation • The acentric factor enters through function α(Tr;ω) as an additional paramter, yield 3-parameter corresponding state correlations: – The Soave/Redlich/Kwong (SRK) equation – The Peng/Robinson (PR) equation Table 3.1 Given that the vapor pressure of n-butane at 350K is 9.4573 bar, find the molar volumes of (1) saturated-vapor and (2) saturated-liquid n-butane at these conditions as given by the Redlich/Kwong equation. 350 Tr 0.823 425.1 q (Tr ) 6.6048 Tr 9.4573 Pr 0.2491 37.96 Pr 0.026214 Tr (1) The saturated vapor Z 1 q Z ( Z )( Z ) Z starts at Z = 1 and converges on Z = 0.8305 ZRT cm3 V 2555 P mol (2) The saturated liquid 1 Z Z ( Z )( Z ) q ZRT cm3 V 133.3 P mol Z starts at Z = β and converges on Z = 0.04331 Generalized correlations for gases • Pitzer correlations for the compressibility factor: Z Z 0 Z 1 – Z0 = F0 (Tr, Pr) – Simple linear relation between Z and ω for given values of Tr and Pr. – Of the Pitzer-type correlations available, the Lee/Kesler correlation provides reliable results for gases which are nonpolar or only slightly polar (App. E). – Only tabular nature (disadvantage) Pitzer correlations for the 2nd virial coefficient • Correlation: BP 0 Pr 1 Pr Z 1 1 B B RT Tr Tr Z Z 0 Z 1 Z 0 1 B 0 Pr 1 P Z B1 r Tr Tr – Validity at low to moderate pressures – For reduced temperatures greater than Tr ~ 3, there appears to be no limitation on the pressure. 0 0.422 B 0.083 1.6 Tr – Simple and recommended. 0.172 – Most accurate for nonpolar species. B1 0.139 Tr4.2 Determine the molar volume of n-butane at 510K and 25 bar by, (1) the ideal-gas equation; (2) the generalized compressibility-factor correlation; (3) the generalized virial-coefficient correlation. (1) The ideal-gas equation RT cm3 V 1696.1 P mol (2) The generalized compressibility-factor correlation 510 25 the acentric factor 0.659 Tr 1.200 Pr 0.200 37.96 425.1 the Lee/Kesler correlation Z 0.865 0 Z 0.038 1 ZRT cm3 1480.7 Z Z Z 0.873 V P mol 0 1 (3) The generalized virial-coefficient correlation 0.172 0.422 1 510 0 B 0 . 139 B 0 . 083 Tr 1.200 Tr4.2 Tr1.6 425.1 Z 1 B0 3 Pr P B1 r 0.879 V ZRT 1489.1 cm Tr Tr P mol What pressure is generated when 1 (lb mol) of methane is stored in a volume of 2 (ft)3 at 122°F using (1) the ideal-gas equation; (2) the Redlish/Kwong equation; (3) a generalized correlation . (1) The ideal-gas equation P RT 0.7302(122 459.67) 212.4 atm V 2 (2) The RK equation RTc 581.67 (Tr ) R 2Tc2 atm 3 b 0 . 4781 ft a ( T ) 453 . 94 Tr 1.695 Pc Pc ft 6 343.1 P RT a(T ) 187.49 atm V b V (V b) (3) The generalized compressibility-factor correlation is chosen (high pressure) P ZRT Z (0.7302)(122 459.67) 212.4Z atm V 2 Pr 581.67 P Z Tr 1.695 343.1 45.4 0.2138 P 189.0 atm Z starts at Z = 1 and converges on Z = 0.890 A mass of 500 g of gases ammonia is contained in a 30000 cm3 vessel immersed in a constant-temperature bath at 65°C. Calculate the pressure of the gas by (1) the ideal-gas equation; (2) a generalized correlation . Vt cm3 V 1021.2 n mol (1) The ideal-gas equation P RT 27.53 bar V (2) The generalized virial-coefficient correlation is chosen (low pressure, Pr ~ 3 ) 338.15 Tr 0.834 405.7 Pr ~ B 0 0.083 27.53 0.244 112.8 Z 1 B 0 B1 the acentric factor TP r r P ZRT 23.76 bar V 1 0.541 Pr Tr 0.422 Tr1.6 0.253 B1 0.139 0.172 Tr4.2 Generalized correlations for liquids • The generalized cubic equation of state (low accuracy) • The Lee/Kesler correlation includes data for subcooled liquids – Suitable for nonpolar and slightly polar fluids • Estimation of molar volumes of saturated liquids – Rackett, 1970: V sat V Z (1Tr )0.2857 c c • Generalized density correlation for liquid (Lydersen, Greenkorn, and Hougen, 1955): Vc r c V V2 V1 r1 r 2 Fig 3.17 For ammonia at 310 K, estimate the density of (1) the saturated liquid; (2) the liquid at 100 bar (1) Apply the Rackett equation at the reduced temperature Tr 310 0.7641 Vc 72.47 Z c 0.242 405.7 V sat Vc Z c(1Tr ) 0.2857 cm3 28.33 mol (2) At 100 bar 100 Pr 0.887 112.8 Tr 310 0.7641 405.7 Fig 3.17 r 2.38 cm3 V 30.45 r mol Vc r1,310K , saturatedliquid r1 2.34 cm 3 310K V2 V1 V 29.14 28.65 r 2 r 2,100bar 2.38 mol