The EU and US Divergence on Competition Law

advertisement

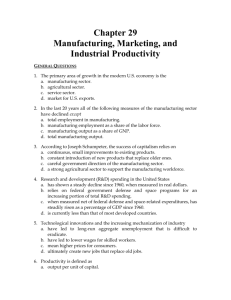

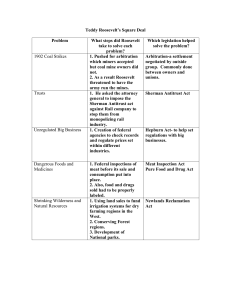

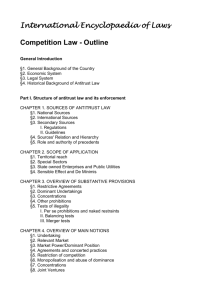

Hristo Hristov Ralina Georgieva EUR 324a The EU and US Divergence on Competition Law The recent decision of the European Antitrust Court on Microsoft renewed the already heated debate on the different approaches to antitrust policies in the United States and in Europe. The categorical claim "We Americans protect competition, while Europeans protect competitors" has come back onto the scene. Antitrust policy aims to increase economic welfare by creating a level playing field. No transatlantic discrepancies up to here. In both the United States and Europe, this is the guiding principle of competition policies. But just how do you best protect consumers’ welfare? It is here that we are entering controversial territory. Trusts and monopolies are concentrations of wealth in the hands of a few. Such conglomerations of economic resources are thought to be injurious to the public and individuals because such trusts minimize, if not obliterate normal marketplace competition, and yield undesirable price controls. These, in turn, cause markets to stagnate and sap individual initiative. Competition law is known in the United States as "antitrust law". The substance and practice of competition law vary from one jurisdiction to another. Protecting the interests of consumers (consumer welfare) and ensuring that enterpreneurs have an opportunity to compete in the market economy are often treated as important objectives. 1 The earliest U.S. antitrust laws were adopted after technological changes , most importantly, the development of a national railway network. These changes turned the U.S. political union into a single economic market. They were adopted with the stated purposes of preventing collusion and strategic entry-deterring behavior. The initial application of the antitrust laws relied on a rule of competition to determine whether business conduct was or was not permitted. The Clayton Antitrust Act of 1915 was enacted in the United States to add further substance to the U.S. antitrust law regime. That regime started with the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890, the first Federal law outlawing practices considered harmful to consumers (monopolies and cartels). The Sherman Antitrust Act 1 was the first United States government action to limit cartels and monopolies. It is the first and oldest of all U.S., federal, antitrust laws. The Clayton act specified particular prohibited conduct, the three-level enforcement scheme, exemptions, and remedial measures. Sherman Antitrust Act, 1890, first measure passed by the U.S. Congress to prohibit trusts; it was named for Senator John Sherman. Prior to its enactment, various states had passed similar laws, but they were limited to intrastate businesses. European Community competition law is one of the areas of authority of the European Union. Competition law, or antitrust as it is known in the United States, regulates the exercise of market power by large companies, governments or other economic entities. EU competition policy was adopted in advance of economic integration. Europe introduced antitrust provisions with its founding act, the Treaty of Rome. But to be sure, back in 1957, competition policy was not high on the agenda of European integration. At the time, this was essentially an irrelevant issue. If anything, strong, and perhaps dominantly, positioned companies were desired in the aftermath of World War II. Competition policy differed significantly from the traditional policies of the original EC6 member states when it comes to business behavior. It was adopted with the stated purpose of furthering 1 Sherman Act, July 2, 1890, ch. 647, 26 Stat. 209, 15 U.S.C. § 1–7) 2 economic integration and to this end prohibited practices that were seen as distorting competition. Still, for decades cartels were tolerated, if not supported, in Europe. But the principles were there. It was only missing a stronger commitment to enforcement. In the last two decades, the European Commission has firmly pushed forward this commitment to make competition policy one of its trademark issues on the global stage. The otherwise often criticized lack of political profile and determination on the part of the European Commission in this case is a strength. A non-politicized European Commission has been able to lead the implementation of a nonpartisan, time-consistent competition policy across Europe irrespective of the political leanings of governments in each country. This has also legitimized EU rulings when national governments have occasionally attempted to support their domestic industries. In contrast, politics do matter in the United States. The heads of the regulatory bodies are politically appointed — and their budgets are decided by the U.S. Congress. The activism of antitrust policies during the Clinton Administration has been replaced by a laxer approach during the Bush years, which started out with an agreement to settle the Microsoft case. In contrast, the determination of Italy’s Mario Monti — the former top EU competition official — has been inherited and continued by his successor, the Dutch Neelie Kroes. In March, 2008, Kroes said the antitrust policies of the 27- member state bloc and the US continue to converge. Speaking in Washington, Kroes said: 'I firmly believe that our systems are on a path of convergence.’2 A couple of days later, Bush administration officials vowed to enforce more strictly antitrust law in their remaining months in 2 Thomson Financial News http://www.forbes.com/afxnewslimited/feeds/afx/2008/03/28/afx4826631.html 3 office. Thomas Barnett, the Justice Department's top antitrust official, said the agency will pursue "aggressive but appropriate merger enforcement."3 Nowadays, competition is an important part of ensuring the completion of the internal market, meaning the free flow of working people, goods, services and capital in a borderless Europe. The antitrust area covers two prohibition rules set out in the EC Treaty. First, agreements between two or more firms which restrict competition are prohibited by Article 81 of the Treaty, subject to some limited exceptions. This provision covers a wide variety of behaviours. The most obvious example of illegal conduct infringing Article 81 is a cartel between competitors (which may involve price-fixing or market sharing). Second, firms in a dominant position may not abuse that position (Article 82 of the EC Treaty). This is for example the case for predatory pricing aiming at eliminating competitors from the market. The European Commission has jurisdiction over largescale mergers and acquisitions affecting more than one EU Member State and exceeding certain thresholds. The Commission can fine antitrust violators. Like the US government, it is entitled to review mergers between non-EU companies with certain revenue thresholds that conduct significant business in the EU. Moreover, unlike US antitrust law, EU law also ensures that competition is not hindered by the intervention of national authorities. In that respect, EU law prohibits state aid granted by EU members that distorts competition in the Internal Market. The EU’s September 2007 Microsoft court ruling is an example of how regulations can have impacts beyond national borders. The EU has taken a much tougher stance against Microsoft Corp.'s alleged monopolistic conduct than the U.S. has, fining the software giant a total of $2.4 billion in the past several years. European authorities are also investigating Intel Corp. for alleged anticompetitive conduct, while the FTC has so far refused to begin a similar probe. Andrew Gavil, an antitrust law 3 The Associated Press http://news.moneycentral.msn.com/ticker/article.aspx?Feed=AP&Date=20080328&ID=8404425&Symbol=TOC 4 professor at Howard University, said the Bush administration has been "much more cautious" than the EU about enforcing competition law against companies such as Microsoft,which dominate their industries. Still, the European Commission seeks ways to cooperate with US authorities, such as the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. Principal elements of cooperation are mutual information about enforcement activities, coordination of enforcement activities and exchange of non-confidential information. The intensity of cooperation is increased if the parties to a case have granted a waiver allowing the exchange of otherwise protected information. Currently, the EU and the US are exploring a second-generation agreement, which would allow for the exchange of confidential information and facilitate cooperation in the fight against cartels. When it comes to international trade, it is important to mention the existence of the antidumping rules. AD rules have originally been introduced in order to prevent foreign suppliers from restricting competition on domestic markets. In other words, initially AD rules were a necessary addendum to national competition laws, which could not be enforced extraterritorially. Frontrunner were the United States with the adoption of an addendum to the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890 – the Wilson Tariff Act which was adopted in 1894 and which indeed was the world’s first AD law. The Sherman Antitrust Act was adopted to prevent competition restraints in trade between the U.S. states as well as in international trade from or towards the U.S. In the course of time the AD rules lost sight of their initial objectives and, furthermore, they also began to deviate substantially from the commonly accepted norms and standards of competition policy and law. The EU trade policy instruments and legislation are in line with applicable WTO and other international agreements on unfair trading practices. The EU takes care that European business and industries are not disadvantaged by unfair and injurious practices from other trading partners. AD measures were created to counter dumping practices, the most frequently encountered trade5 distorting practices. Dumping occurs when manufacturers from a non-EU country sell goods in the EU below the sales price in their domestic market, or below the cost of production. Existing Community rules were replaced by a new Anti-Dumping regulation which came into force on 1 January 1995. This in turn was updated by Regulation 384/96, which came into force on 6 March 1996. This Regulation incorporates measures agreed in the Uruguay Round of the GATT. It also imposes strict time limits for the completion of investigations and decision-making to ensure that complaints are dealt with rapidly and efficiently. The substantial potential for discrimination, which results from significantly differing procedural rules of AD versus competition rules has also been largely ignored up to now. To begin with, in dealing with AD complaints domestic authorities normally follow the factual market definition of the applicant without conducting analyses of their own. This means that the definition of the relevant market is de facto left to the suing domestic sector or to the acting suing trade association, respectively. Furthermore, the country of import normally is considered as the only geographically relevant market due to non-existence of generally accepted legal guidelines on how to define it. Finally, in AD trials there is no need to prove that the foreign competitor accused of dumping enjoys a dominant position in the relevant market (while in competition case sanctions can only be imposed for the abuse of such a position). This leads to an interesting question: How many AD cases would lead to the imposition of sanctions, if antitrust rules had been applied instead? According to an important study by Messerlin, who performed this test on all AD investigations conducted by the European Commission during the 1980ies, the market share of the foreign companies was less than five percent in 56 percent of the cases, and less than 25 percent in more than 90 percent of the cases. A similar study by Niels and Ten Kate, which analysed AD cases of OECD-member states between 1979 and 1989 and which is not publicly accessible, confirms this 6 result. Therefore, if the procedural rules of competition policy would also be applied in AD cases most complaints would have failed. Another turning point in considering the differences between AD and competition policies is the application of fidelity rebates. Fidelity rebates are rewards or discounts given to customers who purchase all or a specified portion of their requirements for a given product or service from a dominant firm. In Europe, the Commission and the European Court of Justice have come close to establishing a per se rule against fidelity rebates granted by a dominant firm, the only exceptions being short-term discount programs and volume discounts that are cost-justified and open to all customers on equal terms. In the United States, by contrast, economists tend to view any reduction in price by a leading firm as moving prices toward the competitive ideal so long as the resulting prices are not below cost. This difference in approach is illustrated most starkly in the treatment of Virgin Atlantic’s complaint about British Airways’ incentive system for travel agents, which gave agents extra commissions in return for meeting or exceeding the previous year’s sales of BA tickets. The European Commission found BA’s incentive program to be an abuse of dominance. By contrast, when Virgin sued BA on the same theory in the United States, the trial court granted summary judgment for BA and that judgment was affirmed on appeal. While Europe's per se approach may unnecessarily discourage some procompetitive discounting, there are some in the United States who view the approach of the U.S. courts as too laissez faire. When it comes to predatory pricing, the U.S. law concerning that matter has been reasonably clear at least since the Supreme Court decided the Brooke Group v. Brown & Williamson case in 1993. There the Court held that to be found predatory, conduct must satisfy a two-part test: (1) the allegedly predatory price must be below an appropriate measure of cost, and (2) there must be a dangerous probability that the alleged predator will be able to recoup its losses through monopoly prices once its rivals exit the market. The European Court of Justice has adopted the first leg of the 7 Brooke Group test, but has expressly declined to adopt the second leg, holding that recoupment is not a necessary element of predation under Article 82. In addition, whereas most U.S. courts have held that the appropriate measure of cost is average variable cost, the ECJ left open the possibility of finding prices above average variable cost but below average total cost predatory if they are “part of a plan for eliminating a competitor.” Another area in which we see a potentially significant difference between U.S. and EU competition law relates to the use of the so-called “essential facilities” doctrine to compel access to a dominant firm’s facilities. While the essential facilities doctrine originated in the United States, it was construed very narrowly, limiting it largely to regulated utilities and joint ventures, out of fear that its overbroad application would both chill incentives to invest and innovate and require antitrust agencies to undertake the uncomfortable task of having to regulate the terms of access. This issue is currently a hot topic of debate in the United States due to the seemingly conflicting decisions of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in ITS v. Kodak and the Federal Circuit in CSU v. Xerox. Both cases involved the issue of whether a manufacturer of photocopiers could refuse to license its parts to rivals in the aftermarket. A similar debate is ongoing in Europe as a result of two cases, Magill and IMS, applying, or attempting to apply, the essential facilities doctrine to intellectual property. In Magill, the ECJ ordered television stations in Ireland to license their program listings to a competitor seeking to create a single guide for all channels. In IMS, the Commission concluded preliminarily that IMS had abused its dominant position by refusing to license to its competitors in Germany its copyrighted “brick structure” — a system for dividing the country into geographic units for collecting data on pharmaceutical sales. On appeal, the Court of First Instance (CFI) suspended the Commission’s interim decision. Supporters of the application of the essential facilities doctrine in these cases have argued that they both involved “extraordinary circumstances” in that the 8 copyrights in question did not involve the kind of creativity copyright law is designed to encourage and that the decisions therefore should not undercut the incentive to invest and innovate. The final area of divergence is what is called monopoly leveraging in the United States — that is, using a dominant position in one market to gain a competitive advantage in another. Most U.S. courts have held that it is not unlawful for a firm with a monopoly in one market to use its monopoly power in that market to gain a competitive advantage in neighboring markets, unless by so doing it serves either to maintain its existing monopoly or to create a dangerous probability of gaining a monopoly in the adjacent market as well. Under EU law, by contrast, it is an abuse of dominance for a firm that is dominant in one market to use that position to gain a competitive advantage in a neighboring market in which it is not dominant even if the conduct is not shown to be likely to create a dominant position in the second market unless the dominant firm can show a legitimate business justification for its conduct. On May 2, 2001, Division of the U.S. Department of Justice announced that it had reached an agreement in principle with General Electric Company and Honeywell International Inc. That resolved the Division’s antitrust concerns with the companies’ proposed merger. On May 16, 2001 the Canadian Competition Bureau informed the companies that it would not take any action to challenge their merger. On July 3, 2001, the European Commission announced that it had determined to prohibit the transaction. First and foremost, the divergence exposed in GE/Honeywell is rooted in fundamental substantive and economic differences in doctrine between the United States and EU merger regimes. In particular, GE/Honeywell makes clear that EU regulators will invoke “portfolio effects theory” to block conglomerate deals that they fear will cause leading firms to become even more effective competitors. In contrast, in the United States, lower prices resulting from mergers are welcome, even when they are predicted to cause leading firms to gain market share. Second, the procedures in place in Europe contributed to the ability of the Competition Commissioner to block 9 the proposed merger of GE and Honeywell based on dubious economic grounds and very weak evidence. In particular, the absence of timely and independent judicial review of the Commissioner’s decision that a combination is incompatible with the Common Market gives enormous discretion to the Competition Commissioner and to the Commission’s Merger Task Force. The case exemplifies that the EU can find dominance in a bidding market based on the ability of the firm in question to win bids through aggressive discounting whereas in the United States dominance would be found in bidding markets when rivals were unable to offer credible, attractive alternatives so that the firm in question was not forced to compete aggressively to win. These are diametrically opposed approaches to the assessment of dominance, or monopoly power, in bidding markets. A very similar divergence occurs around the concept of “foreclosure.” As a matter of economics, we would use the term “foreclosure” to refer to situations where one firm uses its monopoly power to limit the ability of others to compete effectively against it. Classic examples of foreclosure by a firm with monopoly power would be tying and exclusive dealing. Readers of the EU’s final decision in GE/Honeywell will find a very different usage of the term “foreclosure.” In the EU, a firm that wins by serving customers’ needs may be characterized as having “foreclosed” its rivals. For example, the Final Decision states “Indeed, the ability to put together its considerable financial strength . . . and to offer comprehensive packaged solutions to airlines have given GE the ability to foreclose competition.” Perhaps more than anything else, divergence in GE/Honeywell can be traced to very different views of what constitute “efficiencies” in mergers. The European Union has adopted two major new regulations on antitrust. Both took effect on May 1, 2004. The first regulation, dealing primarily with competition rules, includes a number of provisions that considerably strengthen the power of the Competition Commission. The second important antitrust regulation, which deals with mergers, also took effect on May 1, 2004. The EU 10 has authority over any proposed merger, regardless of the nationality of the companies involved, if the transaction meets two revenue thresholds—if the combined companies would exceed 5 billion euros in annual revenue worldwide, and if at least two of the merging companies would each have annual revenue exceeding 250 million euros inside the EU. Prior to 2004, the EU merger test involved the question of whether the combining companies would create or strengthen a dominant player (usually meaning the firm with the largest market share) in a particular market, based on the “abuse of dominant position” concept from Article 82 of the EC Treaty. The new regulation revises the merger test, allowing the EU to block mergers that “significantly impede effective competition. This revision brings the EU test closer to the U.S. standard for mergers set by the Clayton Act, which prohibits mergers when the effect “may be substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.” However, an important difference remains in that U.S. antitrust authorities must go to federal court to request an injunction to block a proposed merger. In contrast, the EU’s Competition Commissioner can block a merger without prior court involvement. The EU merger reform package also includes new Horizontal Merger Guidelines providing detailed guidance on how the Competition Commission will evaluate proposed mergers between current or potential competitors. These guidelines represent yet another step toward greater conformity with U.S. antitrust law, which has similar guidelines.Of course, the practical impact of the EU’s revised merger regulation will not be known with certainty until it has been used in a number of cases. The latest big step towards transatlantic co-operation concerns EU-US Air Transport Agreement that took effect on 30 March 2008. For the first time, airlines can fly without any restrictions between any point in Europe to any point in the US. “The start of a new era”, according to Jacques Barrot of the European Commission. The EU-US Air Transport Agreement is expected to enhance competition by allowing, for the first time, EU or US airlines to serve any routes between 11 Europe and the United States. The agreement will be applied as of the end of March 2008, pending ratification. It also calls for the Commission and Dapartment of Transportation to develop a common understanding of trends in the airline industry in order to promote compatible approaches on competition issues. The competition policy of the European Union is a supranational effort to regulate the single market. Although more recent than American anti-trust regulations, it appears to be a bit more consolidated. Efficient primary and secondary legislation enforced by the Commission, National Competition Authorities aided by the ECJ constitute another type system of market regulation and consumer protection than the American one. Future efforts towards further convergence are required so that the two system of regulation can benefit from each other. REFERENCES: Anderson, S. P., Schmitt, N., Thisse, J. (1995): “Who Benefits from Antidumping Legislation?”, Journal of International Economics 38, 321-337. Blonigen, B. A., Prusa, T. J. (forthcoming): "Antidumping", in Harrigan, J. (editor), Handbook of International Trade, Oxford, U.K. and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers. Finger, J. M., Hall, K. H., Nelson, D. R. (1982): “The Political Economy of Administered Protection”, American Economic Review 72, 452-466. Finger, J. M. (1993): Antidumping: How It Works and Who Gets Hurt, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. Finger, J. M., Ng, F., Wangchuk, S. (2001): “Antidumping as Safeguard Policy”, World Bank Working Paper No. 2730. 12 Gallaway, M. P., Blonigen, B. A., Flynn, J. E. (1999): “Welfare Costs of US Antidumping and Countervailing Duty Laws”, Journal of International Economics 49, 211-244. General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (1958): Anti-Dumping and Countervailing Duties, Geneva. Guzman, T. A. (forthcoming): “International Antitrust and the WTO: the Lesson from Intellectual Property”, Virginia Journal of International Law. Haaland, J. I., Wooton, I. (1998): “Anti-Dumping Jumping: Reciprocal anti-Dumping and Industrial Location”, Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv 134, 340-362. Hansen, W. L., Prusa, T. J. (1997): “The Economics and Politics of Trade Policy: an Empirical Analysis of ITC Decision Making”, Review of International Economics 5, 230-245. Hartigan, J. C. (2000): “An Antidumping Law Can Be Procompetitive”, Pacific Economic Review 5, 5-14. Fox, Eleanor M., "GE/Honeywell: The U.S. Merger that Europe Stopped - A Story of the Politics of Convergence" (July 2007). Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1002647 Richard A. Posner, Antitrust Law (2d ed., Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001). XXKF1649.P66 2001 D'Angelo Law Library, Reserve Reading Room. Herbert Hovenkamp, The Antitrust Enterprise: Principle and Execution (Cambridge, Mass. : Harvard University Press, 2005). HF1414.H68 2005 Regenstein Bookstacks. See also review by Professor Randal C. Picker, 2 Competition Policy International 183 (2006)). 13