Viral Reproductive cycles: Viruses infect every kind of cell. Usually

Viral Reproductive cycles:

Viruses infect every kind of cell. Usually there is a high degree of host specificity.

For example, not only are plant viruses specific for plants, but they are also specific for a particular species of plant. It’s the same for animal, fungal, protist, and bacterial viruses. However, viruses can adapt to new species, as in human viruses that “jumped” from birds or pigs.

All cells use DNA to store information. Viruses are very diverse, and can store their information as either DNA or RNA.

For a virus to get into a cell, it either has to force entry (if the host has a cell wall), or induce the cell to let it in (animal viruses w/o cell walls). Many plant viruses gain entry by way of herbivorous insect vectors. (Thus, viral diseases of plants are often controlled with insecticides, in a manner similar to controlling malaria by spraying insecticide to kill the mosquitoes.)

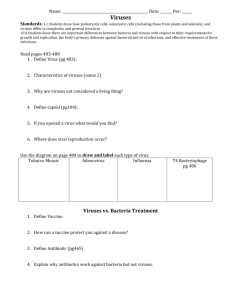

Once inside the host cell, viruses do one of two things: First, they can commandeer the host cell’s machinery for nucleic acid replication and gene expression to multiply en masse. Unlike cells, viruses don’t divide. They multiply….fast. Then the legions of new virus particles destroy (lyse) the cell and emerge to infect new cells. This is called the LYTIC CYCLE.

In some cases, the virus incorporates its genes into the host cell’s genome. If it’s an

RNA virus like HIV, it has to made a DNA copy of its RNA (reverse transcription) and then incorporate it into the host genome. At this stage the viral genome is now part of the host cell genome. At this stage the virus is called a PROVIRUS. As the host cell with the viral genome divides, the virus divides along with it. The provirus may remain part of the host genome for a short time or indefinitely (as in forever). Or it may – from some environmental cue – pop out and go through a lytic reproductive cycle. This is referred to as the LYSOGENIC CYCLE.

These two (lytic and lysogenic) cycles have been studied most extensively (and far longer) with viruses that infect bacteria. For some reason, viruses that infect bacteria are called BACTERIOPHAGES or just PHAGES. Thus, the “provirus” in this case is called a PROPHAGE.

A provirus or prophage can actually alter the molecular behavior of its host cell without killing it. In the case of pathogenic bacteria, the prophage/provirus can increase or decrease virulence.

Molecular evidence tells us that viruses have been doing all of this for about as long as cells have been around. This is one of the mechanisms for horizontal gene transfer (HGT), called TRANSDUCTION. In recent years, it has been discovered that retroviruses (like HIV) have a strong affinity for germ line cells, and thus insure that they will be passed on to future generations.