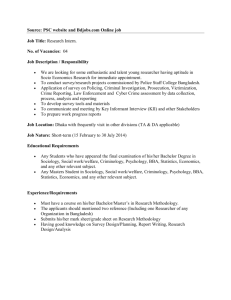

draft - Tdi

advertisement