Thomas Dodson

October 28, 2003

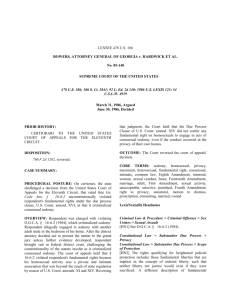

On June 26 of this year a 6-3 majority decision of the United States Supreme

Court in the case of Lawrence v. Texas declared all state laws proscribing non-procreative

sex to be unconstitutional infringements of the right of citizens to "engage in private

conduct without government intervention" (Lawrence 41). Although the Texas law only

prohibited sexual contact between those of the same sex, the court's ruling effectively

overturned a 1986 decision that upheld a Georgia statute criminalizing "any sexual act

involving the sex organs of one person and the mouth of the other" (Bowers2). Although

Georgia's sodomy law made no distinction regarding the genders of persons engaged in

criminal sexual acts, Justice White's majority opinion in Bowers v. Hardwick restricted

itself to commenting upon the legal status of homosexual sodomy. The choice of the

court in Hardwick to interpret the Georgia statute as simply a ban on same-sex sodomy

and the decision of the Texas legislature to target only gay sex raises the issue of whether

there is a constitutional basis for the exclusion of gay people from the liberties other

Americans enjoy. Examining these cases should also lead us to question the purposes

and principles of laws regulating private sexual conduct.

This slim volume, which reproduces the complete text of the courts' opinions in

Lawrence and Hardwick , will be of great interest to legal scholars, historians, political

scientists, and activists. Articles from the popular and alternative press included in the

volume will be of special concern to those wishing to place the courts' landmark

decisions within a social and political context. The collection would have benefited,

1

2

Pagination refers to Syllabus

Footnote 1

Dodson 2

however, from the inclusion of significant precedents (Griswold and Eisenstadt ), more

extensive legal commentary, and a broader sample of the ongoing public and scholarly

deliberation on the issues raised by the decisions.

In 1982, Michael Hardwick was arrested in his bedroom by an Atlanta police

officer for engaging in oral sex with his partner. In the majority decision in Bowers v.

Hardwick, the court rejects Hardwick's claim that the Georgia statute violates his

fundamental right to privacy and self-determination in his intimate associations. Instead,

the majority decision frames the case as a plea for special rights, concluding that "the

Constitution does not confer a fundamental right upon homosexuals to engage in

sodomy" (Bowers par. 4).

The decision maintains that the right to homosexual sodomy is not fundamental; it

is neither integral to liberty and justice, nor is it well-established in America's "history

and tradition" (Bowers par. 22). Thus, it does not meet the standard for "rights qualifying

for heightened judicial protection." (Bowers par. 22). The court cites the many state

statutes outlawing sodomy as proof that a right to gay sex would, in fact, run counter to

the nation's history and established conventions. The court also maintains that the

Georgia statute possesses a rational basis in that it reflects the majority opinion of

Georgia's citizens that homosexuality is immoral. In his concurring opinion, Chief

Justice Berger makes the questionable claim that "decisions of individuals relating to

homosexual conduct have been subject to state intervention throughout the history of

Western civilization" and that "Judeao-Christian moral and ethical standards" provide a

compelling foundation for the Georgia statute (Bowers par. 30).

Dodson 3

Justice Stevens, joining the dissenting opinion, points out that, although the

Georgia law makes no distinction regarding the identities of those engaged in sodomy,

the majority decision clearly does. The strategy of the majority decision, to limit the

constitutional question to "the right to homosexual sodomy," serves to obfuscate the

unconstitutionality of the statute as written. An examination of prior cases makes it clear

that Georgia cannot enforce its sodomy law in relation to married or unmarried

heterosexual couples, who already enjoy constitutional protection for their private, sexual

behavior. Thus, although the state of Georgia is compelled to justify its selective

enforcement of the law, there is no "neutral and legitimate interest" by which the state

can do so (Bowers par. 68).

The law in question in the case of Lawrence v. Texas differs from the Georgia

statute in that its ban on certain sexual acts only applies if the agents are members of the

same sex. Delivering the opinion of the majority, Justice Kennedy's argument follows

that of Justice Blackmun's dissenting opinion in Hardwick. Both maintain that the

relevant constitutional issue in these cases is not the freedom to engage in homosexual

sodomy, but rather the freedom from government interference in private conduct secured

by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In order to adjudicate the

case, the majority opinion re-examines, and finally overturns, the decision of the White

court in Bowers v. Hardwick.

In his dissenting opinion, however, Justice Scalia re-asserts the claim of the

White's majority opinion in Hardwick, that the issue is not a broad "freedom from" but a

narrow "freedom to." He also maintains that a majority conviction that some sexual acts

are immoral "constitutes a rational basis for regulation" (5). Scalia also disputes the

Dodson 4

majority interpretation of the Due Process Clause, pointing out that states are allowed to

deny the liberties of their citizens, so long as the rights in question are not "fundamental"

ones and the citizens are not deprived of due process of law. Following Justice White,

Scalia maintains that a right to sodomy is not fundamental, and therefore does not merit

the "heightened scrutiny" of the high court (8).

The cases and commentary contained in this collection direct us to the most

fundamental questions regarding laws regulating sexual conduct: What purpose should

these laws serve, and what principles should guide us in enacting, affirming, or

overturning them? While Justices Berger and Scalia maintain that sodomy laws in the

United States have always sought to specifically deny a right to private and consensual

gay sex, Justice Kennedy argues convincingly that "there is no long-standing history of

laws directed at homosexual conduct as a distinct matter" (7). Kennedy argues that "early

American sodomy laws were not directed at homosexuals as such but instead sought to

prohibit non-procreative sexual activity more generally" (8). Patterns of enforcement

further suggest that these laws were not intended to regulate "consenting adults acting in

private," but rather were designed to provide an avenue of legal redress for victims of

"sexual assault[s] that did not constitute rape as defined by criminal law" (8).

Laws regulating private sexual practice could, conceivably, serve the purpose of

defending the rights of victims of sexual assault without unduly infringing the rights of

others to privacy and equal protection. Clearly, this would involve overturning statutes

of a more recent vintage that specifically target the consensual sexual activity of samesex adults. As National Review columnist Robert P. George notes, this approach would

require a "criterion or set of criteria [. . .] by which courts [could] distinguish

Dodson 5

constitutionally protected from unprotected sexual conduct" (par. 6). Although George

shudders at the thought of adopting consent as a guiding principle for sexual regulation

(claiming that it would throw open the orifices of the body politic to all sorts of

unwelcome perversions), it may be most defensible choice.

George argues that previously marriage represented the dividing line between

protected and unprotected. Clearly it is not this simple as this; previous cases have

asserted the privacy of the heterosexual bedroom, whether the couple was married or not.

Thus, George fails to acknowledge that the de facto principle of constitutionally protected

sex has been heterosexuality, not marriage. Further, such a principle is not adequate to

the task of protecting victims of sexual assault when they are married to their assailant.

An obvious alternative principle, only protecting sexual conduct sanctioned by traditional

notions of sexual morality, seems particularly narrow and unworkable. The principle of

tradition would not allow for shifts in the social values of the American people to be

reflected in their courts. In short, it would deny our human capacity for ethical inquiry,

and subject our intimate sexual lives to the tyranny of our ancestors.

The adoption of a principle of consent to guide the interpretation and adjudication

of laws designed to protect individuals from sexual assault is not a simple proposition,

either. To ensure a balance between sexual freedom and the rights of victims of sexual

violence, and to defend against the inevitable charges of loony libertarianism will require

considerable consideration of what "consent" should mean. As legal scholar Marc

Spindelman argues, we should not extend our support to legal "victories" in which the

unconstitutionality of sodomy laws allows perpetrators of sexual violence to go

unpunished. We must also develop a notion of consent that acknowledges the dynamics

Dodson 6

of abusive relationships, regardless of the gender of the partners. Hopefully the present

collection will contribute to a discussion of just these issues.

Word count: 1454

Works Cited

Dodson 7

Bowers v. Hardwick, 478 US 186 (1986).

George, Robert P. "Rick Santorum Is Right: Where Will the Court Go After Marriage?"

National Review Online. 27 May 2003. 27 October 2003.

<http://www.nationalreview.com/comment/comment-george052703.asp>

Lawrence et al. v. Texas, 539 US (2003).

Spindelman, Marc. "Sodomy Politics in Lawrence v. Texas." JURIST. 12 June 1993. Dir.

Prof. Bernard J. Hibbitts. 27 October 2003

<http://jurist.law.pitt.edu/forum/forumnew115.php>.