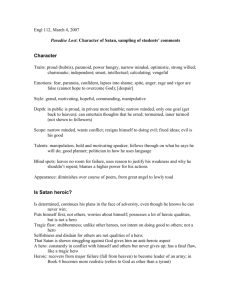

Chapter 1 - The Real Devil

advertisement