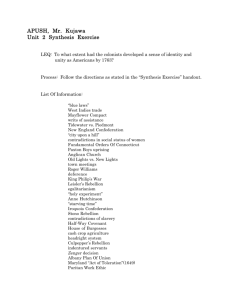

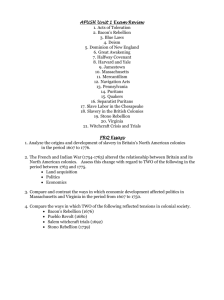

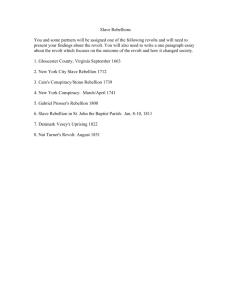

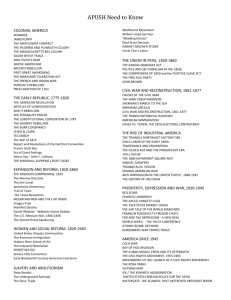

Paper_StonoRebellion_MacKenzie_HIST330

advertisement

STONO: SECRECT SLAVE REBELLION OF SOUTH CAROLINA. James R. MacKenzie HIST 330 April 17, 2008 1 The Stono Rebellion was one of the first major slave revolts ever staged in British North America. In the fall of 1739 some one hundred enslaved Africans living in South 2 Carolina joined together in a devastating march towards Spanish controlled Florida and freedom. The violence of the rebellion produced the deaths of more than 60 whites and 30 enslaved Africans, as well as causing a fear and mistrust all over the British colonies. The rebellion itself was the bloodiest and largest in the entire South Carolina colony. The results of the rebellion also caused laws to be passed that further restricted the movement and holding of slaves. The rebellion had far reaching consequences for all of the British colonies that would influence the institution of slavery everywhere in what would become the United States of America. What is so interesting about the Stono Rebellion isn’t just its causes and aftereffects, but the fact that such a monumental event in what would become American history was so undocumented. It wasn’t until the work of Peter Wood, a Duke history professor in 1974 that the historical community first got a look at a modern historical account on the subject. His work as well as the recent work of Mark M. Smith the distinguished professor of history at the University of South Carolina, which put together previously unknown primary sources about the Stono Rebellion and three modern historians’ interpretations on the event, provides much of what is now known about this historically important rebellion. The primary sources themselves range from accounts of the condition of South Carolina just prior to the rebellion, to an actual first hand account of the rebellion from South Carolina’s Lieutenant Governor William Bull. The Stono Rebellion is like other slave rebellions that took place in the colonial US in that there is no historical evidence to know what the exact cause of the rebellion was. Stono itself has a lot of unique features to consider when looking at the causes of the insurrection. The first thing that comes to mind when thinking of the causes of the 3 rebellion is the condition that slaves were experiencing in the South Carolina colony. Another possible scenario could have been motivation from the Spanish colony of Florida to rebel and march towards Florida as a way of gaining freedom. John K. Thorton’s article on the Stono Rebellion looks at the possible motivation being the slaves African origins. He says that “the South Carolina slaves were in all likelihood not drawn from the Portuguese colony of Angola but from the kingdom of Kongo, which was a Christian country and had a fairly extensive systems of schools and churches in addition to a high degree of literacy (at least for the upper class in Portuguese.”1 Proving anyone of these possible causes for the Rebellion, even today represents an impossible task, but in looking at the events surrounding the insurrection it is important to consider its possible motivations. In looking into the events of the Stono Rebellion scholars must first consider what conditions were like in South Carolina as a whole as well as from the slaves perspective. Early race relations in South Carolina represented a colony that had a majority black slave population and a minority white population that was concerned about the number of slaves in their colony. Just prior to the Stono Rebellion, “a new act was passed in 1734 which established a regular patrol along lines which would be followed for the duration of slavery. Under this statute three commissioners were appointed to supervise the patrol in each militia district.”2 The patrol itself, “were to make the rounds of plantations within their district at least once a month. They could question or search any traveling Negro and they could administer up to twenty lashes to any slave stopped outside his plantation 1 Mark M. Smith, ed., Stono: Documenting and Interpreting a Southern Slave Revolt (Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2005), 76. 2 Peter H. Wood, Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina from 1670 Through the Stono Rebellion (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1974), 275. 4 without a ticket.”3 It is because of this law and ones similar to it that there was a general fear felt among the entire South Carolina colony. White residents were fearful of African slaves they enacted militia patrols, while blacks both free and enslaved were fearful of the militia patrols and the punishments they could receive for being out at the wrong place and time. The growing fears of white residents of South Carolina were not unjustified however. Even prior to the Stono Rebellion of 1739 there were instances of slave hostilities toward their condition. There were two distinct ends of the spectrum as to what slaves in South Carolina did to rebel against their owners, at one end there is violence and death, while others used more subtle forms of retaliation such as poisoning or arson which were harder to trace. In Wood’s book he also explains that slaves may have had awareness of the capabilities of the various plants around them citing that “In West Africa, the obeah-men and others with the herbal knowledge to combat poisoning could inflict poison as well, and use for this negative capability was not diminished by enslavement.”4 The stage was set for a major rebellion to go off in South Carolina, the race relation between whites and blacks were a powder keg waiting to explode. Although there was little reported about the Rebellion at Stono in 1739 historians have recently uncovered documents that help give greater understanding about such a large slave rebellion. What we now know about the rebellion is that “during the early hours of Sunday, September 9, 1739, some twenty slaves gathered near the western branch of the Stono River in St. Paul’s Parish, within twenty miles of Charlestown. Many of the conspirators were Angolans, and their acknowledged leader was a slave 3 4 Wood, The Black Majority, 275. Ibid, 289. 5 named Jemmy.”5 The band of slaves proceeded to the Stono Bridge and broke into Hutchenson’s store, where small arms and gun powder were sold. “The storekeepers Robert Bathurst and Mr. Gibb’s, were executed, and their heads left upon the front steps. Equipped with guns, the band moved on the house of Mr. Godfrey, which they plundered and burned, killing the owner and his son and daughter. They then turned southward along the main road to Georgia and St. Augustine and reached Wallace’s Tavern before dawn. The innkeeper was spared, for ‘he was a good man and kind to his slaves,’ but a neighbor, Mr. Lemy was killed with his wife and child and his house sacked.”6 The group continued on their path of death and destruction, killing any whites they could find and burning their homes to the ground. It was as the group rebelling slaves continued that more and more slaves joined their ranks, some were undoubtedly willing participants in the rebellion, while others may have been forced into their ranks for fear of reprisal from the armed leaders of the rebellion. After they had pillaged and marched their way south 10 miles, the group of rebels stopped at a field. It was while they were in this field that many of them began drinking the liquor they had stolen and began dancing and celebrating their accomplishment. It was in this field the next morning where the group of rebelling slaves was met by a white militia that opened fired and killed many of them, the rest fled or gave up. The one first hand account that we have of the Stono Rebellion happened on sheer coincidence. Lieutenant Governor Bull was returning from a trip to Granville County when at 11:00 in the morning he and his group came upon the rebelling slaves. In his letter he described the event saying, “on the 9th of September last at night a great number of Negroes arose in rebellion, broke open a store where they got arms, 5 6 Smith, 63. Ibid. 6 killed twenty one white persons, and were marching the next morning in a daring manner out of the province, killing all they met, and burning several houses as they passed along the road. I was returning from Granville County with four gentlemen and met these rebels at Eleven a Clock in the forenoon, and fortunately discerned the approaching danger time enough to avoid it, and to give notice to the militia who on that occasion behaved with so much expedition and bravery, as by four a clock, the same day to come up with them and killed and took so many as put a stop to any further mischief at that time, forty four of them have been killed and executed some yet remain concealed in the woods expecting the same fate, seem desperate.”7 The obvious thing that jumps out in this firsthand description is that the number of deaths that it accounts for differs from what scholars believe were the actual numbers. The other thing that differs from modern day analysis of the events of the Stono Rebellion is the belief that the initial encounter with the militia all but ended and killed the rebelling slaves. In fact “at least thirty Negroes (or roughly one-third of the rebel force) were known to have escaped from Sunday’s skirmish in several groups, and their presence in the countryside provided an invitation to wider rebellion.”8 The ensuing days after the rebellion were one of unrest within the colony, as “the entire white colony was ordered under arms, and guards were posted at key ferry passages.”9 White citizens of the colony were rightfully concerned because “some of the rebels from Stono were still at large in late November 1739,”10 and “one of the leaders of the rebellion was not captured until 1742.”11 The Stono Rebellion 7 Smith, 17. Ibid, 65. 9 Ibid. 10 Ibid, 66. 11 Smith, xiii. 8 7 left the colony of South Carolina in a state of shock, and it was precisely this reason that the rebellion wasn’t heavily documented at the time. The Stono Rebellion remains one of the most undocumented historical events in all of US history. The majority of the primary source documents relating to the Stono Rebellion are private correspondences (letters) between various persons residing in colonial British North America. Often the only evidence of the rebellion is a passing mention in a letter such as the letter from Robert Pringle (a South Carolina merchant) to John Richards (a man who he did business with in London), he says “I hope our Government will order effectual methods for the taking of St. Augustine from the Spaniards which is now become a great detriment to this province by the encouragement and protection given by them to our Negroes that run away there. An insurrection has been made of late here in the country by some Negroes in order to their going there and in less than twenty four hours they murthered in their way there between twenty and thirty white people and burnt several houses before they were overtaken, tho’ now most of the gang are already taken or cut to pieces. This happened within three weeks past.”12 In looking at popular newspapers of the time there was only one mention of the rebellion that appeared in the Boston Gazette under the title “A Letter from South Carolina”. It is similar to other contemporary accounts of the rebellion in that it makes it seem like the rebellion was crushed quickly and easily. The letter which was published in November of 1739 read, “about three weeks past we had an insurrection of our negroes, who in one night cut off about 25 whites, and then formed a considerable body, burnt about 6 houses, and sacrificed every thing in their way. We were immediately alarmed, and under arms and first method we took was to secure our ferries and passes by guards; and to send out a 12 Ibid, 9. 8 body upon the scout, which came up with them, and engaged them. They gave two fires, but without any damage, and we returned fire and brought down 14 on the spot, and pursuing after them within two days killed twenty odd more, some hung, and some gibbeted alive. A number came in and were seized and discharged; some are yet out, but we hope will soon be taken.”13 Aside from pursing the rebels that had yet to be captured after initial engagements South Carolina as a colony reacted in ways to try and prevent another Stono Rebellion. The South Carolina government met shortly after the events of the rebellion and together came up with a variety of new laws to help ensure the future security of the colony form other slave rebellions. All of these deliberations resulted in what is generally know as the Negro Act of 1740 which “redefined slaves as personal chattels (they had been considered freehold property until then), regulated behavior of whites as well as blacks, and became the legal basis of South Carolina’s slave code into the nineteenth century. The act tried to curtail the excesses of slavery by placing restrictions on, for example, when and how much masters could work or punish their slaves; it also limited the small freedom formerly enjoyed by slaves.”14 Although these laws were passed to place even more restrictions on slaves some of them were ignored in that “slaves still bought intoxicating liquors, sold goods, and even carried guns.”15 Another interesting aspect about the Stono Rebellion is that although it was a slave rebellion, many white colonists considered its motivations to be held within promises made by the Spanish government in Florida for freedom. This motivation was considered in one of the first American historical documents written by Alexander 13 Smith, 12. Ibid, 20. 15 Ibid. 14 9 Hewatt (1740 – 1824) on the Stono Rebellion. In it he says “long had liberty and protection been promised and proclaimed to them (slaves) by the Spaniards at Augustine, nor were all the Negroes in the province strangers to this proclamation.”16 This fear of the Spanish government trying to lure slaves into rebellion and to run off to Florida was realized when “two Spaniards were caught in Georgia, and committed to jail, for inciting slaves to leave Carolina and join their regiment.”17 Although the motivations behind the Stono Rebellion remain unknown the rebellion no doubt scared not only the colonists but the British Government as well. The Stono Rebellion was one of the largest and bloodiest slave rebellions in all of colonial US history. By its conclusion some 60 white colonists were dead, 30 rebel slaves were dead, and 10 miles of destruction lay in its wake. The rebellion had dramatic consequences on the institution of slavery in South Carolina for decades to come. The laws passed in the wake of the Stono Rebellion were meant to further control the growing black slave population through greater restrictions on their already severely limited freedoms. The importance of the Stono Rebellion is a recent phenomenon due to the fact that many of the documents about its events were only recently uncovered by modern historians. Despite its significance Stono remains one of the most undocumented rebellions in US history, and its effect and importance are only just being realized by historians. BIBLIOGRAPHY 16 17 Smith, 33. Ibid. 10 Smith, Mark M., ed. Stono: Documenting and Interpreting a Southern Slave Revolt. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2005. Wood, Peter H., Black Majority: Negroes in Colonial South Carolina form 1670 Through the Stono Rebellion. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1974. 11