INTR310/710 - International

advertisement

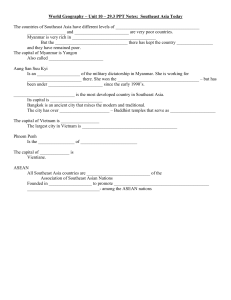

INTR13/71/72-310 R. James Ferguson © 2005 Week 12: The New International Relations From Crisis Management to Strategic Governance Topics: 1. Political Realism as the Lessons of Conflict 2. Adaptive Change in Strategic Thought: From Human Security Towards Humane Governance 3. Diversifying Pragmatism in the 21st Century 4. Bibliography and Further Reading 1. Political Realism as the Lessons of Conflict Realism has provided some genuine insights into the international system, and remains an important safeguard against 'wishful thinking' and 'utopian idealism', both of which can lead to disastrous failures in international policy, e.g. in the construction of European affairs after World War I. As we saw in lecture 2, the realist tradition in international relations is based on the very real experiences of conflict in human affairs, and in the centrality of power in global politics. This tradition was well established in ancient thinkers, both East and West. In ancient Greece, the historian Thucydides wrote one of the first realist accounts of the dire necessities of state leadership amid the problems of complex alliance systems and endemic warfare (concerned with the 5th century Peloponnesian War). Similar problems emerged in early China (8th-3rd centuries B.C.), and realist thought would strongly colour (though not dominate) Chinese thinkers such as Sun Tzu and Sun Ping, and eventually even influence modern leaders such as Chairman Mao (Sun 1991). Likewise, a realist tradition would emerge early in Indian thought in the type of statecraft recommended by Kautilya (for a range of such early systems of international relations, see Watson 1992). Interestingly enough, Chinese statement from 770 B.C. onwards tried a combination of statecraft, diplomacy, and defensive wars to limit the power of aggression, but this could generate a stable multi-state system (Creel 1970; Walker 1953). Empire builders, of course, often relied on economic, military and religiously-defined power to create and hold their extended territorial states, e.g. the Macedonians, Romans, Chinese, the Muslim Caliphates, Persian, Mongolian, Spanish and British empires. In different ways, each of these empires relied on military, economic and political power to maintain themselves, though religious elements were often also used to launch phases of expansion or maintain ideological dominance. In the modern period, combinations of transition from earlier kingdoms, military ability, political opportunism, and nationalist aspiration have been used to create modern states, e.g. Germany and Italy, or to fragment existing states into smaller new states, e.g. as in region of former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union. Nationbuilding then, often relies on the realist use of force, alongside the cultural forces of nationalism and the politics of national identity. Week 12 1 We can review some of the key layers of the realist position in international relations, which include: The effort to look at actual 'real' situation in the world, including negative aspects. An emphasis on power, and augmentation of power in international relations. An emphasis on the state as the key actor in international relations. An emphasis on national interests as the basis for the motivation of leadership groups. An emphasis on behaviour and outcomes, not ideas. A reliance on a negative view of human nature as being essentially self-interested An emphasis on elite leadership, plus a mobilised mass following, though genuine participation is often limited. Ideas and values are often used to support the regime, and thus are accorded a real but subordinate role in power formation and utilisation (see Morgantheau 1985). An emphasis on strategy and power projection in the international system. At the same time there are real dangers in becoming addicted to a narrow realist position, which has now emerged as an ideology justifying the status quo. When survival or power dominance is at stake, or relative position within economic and diplomatic hierarchies, then self-interest may be both misunderstood and far from enlightened (for such psychological factor during periods of crisis, see Farrar 1988; Morganthau 1985). This means that leaders may over-react, in part due to domestic political pressures and the need to gain support within democracies. The result was anything but a sober and realistic assessment of their situation. In such conditions, assessments of power and power balance may also become distorted. The key point, moreover, is that under conditions of intense conflict, excessive fear or hope, the realist use of power may not always just based just on rational assessments - a range of other factors including nationalism, stereotyping and demonisation may be brought into play, e.g. the range of such mis-perceptions in the public arena in relation to the cultures of Iraq and Iran, in part drawing on 'Persian' stereotypes (see Seymour 2004). In the same way, much of the international relations discipline today, though rightly concerned with strategic conflicts, political realism, and international competition, has been conditioned by the experiences of World War II and the subsequent experience of the Cold War period. Many institutions for global governance, e.g. the UN, UNSC, the IMF, World Bank and related agencies were born out of this period, and sought to promote peace, trade and one vision of development, but conditioned by the experience of war and the leadership of a core group of victor nations. In spite of some reform, extension and adaptation, e.g. of international financial institutions and new emphases on environment and development via UN conferences and agencies, it is not certain that these overlapping agencies can effectively implement the tasks they have set themselves, e.g. global financial stability, 'weak sustainability environmentally or the Millennium Development Goals (see lectures 6, 7, 11). Nor is it certain that Inter-Governmental Agencies (IGOs) are well suited to the Week 12 2 needs of the 21st century, including the diffuse transnational challenges of international terrorism, civil war, refugees and labour flows, economic instability, transboundary environmental problems or conflict over key resources (see Le Billon 2005; Klare 2002). In other words, the intense and largely negative experiences of earlier periods have influenced the judgement of many practitioners in foreign policy, international governance and international institutions. The experiences of all thinkers and actors, of course, influence their judgement and the assumptions used in analysis. But in some cases this experience can be so intense that it conditions people to carry forward models from an appropriate setting to new settings where they are no longer appropriate. A few areas where this has learning under new conditions has not occurred, or only evolved slowly, can be listed: Week 12 The collapse of the Soviet Union has sometimes been viewed as signalling the end of Communism and Socialism globally, and end of ideologically driven conflicts and history (Fukuyama 1992). As a result, some have turned to look at China and argue that the same forces will fragment the People's Republic of China, or at least in the medium lead to the end of its unique political system and increasing pressure for democracy (for such expectations, see Terrill 2005; Schell 2004; Segal 1994; Segal and Goodman 1994). The two cases, however, are not that analogous: not only is Communism in China affected by what Deng Xiaoping called 'Chinese Characteristics', but China has much stronger ethnic cohesion with minorities less dominant in most of their homelands (92% of China is ethnic Chinese). Furthermore, 'institutional learning' (for this approach, see Haas 2000) would suggest that the Chinese leadership and many people in China have learnt from observing what happened in the Soviet Union and will intentionally avoid such transformations, allowing economic transition and greater political openness but no immediate transition into a democracy with opposition parties (for these issues see Schell 2004; Nathan 1993a & 1993b; Nathan & Shi 1993). For China itself, only Tibet, Xinjiang and Taiwan are likely to exhibit such trends politically, and the PRC has relative power preponderance within Tibet and Xinjiang itself. Some economic and cultural decentralisation is underway, is not likely to force rapid transition (for the problems of 'monoculturalism' in China, see Dreyer 1999). Furthermore, by allowing economic reform, the regime has managed to meet some of the needs and expectations of key segments of the population (beginning with the 'peasants'), thereby avoiding extreme political destabilisation. A similar path has been unevenly pursued with the cautious economic reforms and preparing for a future collective leadership in Cuba (see Robinson 2000), but followed by a harsh clamp down in the regime through late 2002-2004, suggesting increased pressure on the Castro government. We cannot directly move from the Soviet and Eastern Europe experiences to universal arguments concerning the fate of communism, socialism and other regimes (Palmer 1997). More generally, PRC has mobilised elements of culturalism, nationalism, and economic growth to support its regime domestically, while using elements of soft and hard power to gradually assert itself regionally and in global affairs (see lectures 4 & 5). On this basis, it will be very difficult to either contain China, or to directly 'absorb' it into the existing regime of international norms and institutions. 3 Containment and competitive policies can also run along too-well grovved channel. Tensions between the US and PRC, for example, tend to work along a cycle of mutual interests (trade, WTO entry for China, PRC support in easing the North Korea crisis through 2003-2005), then diverge as incidents remind the two leaderships of their different view of world order. The temptation to use the past strategy of containment, however, exists, because the strategy was seen (from one point of view) to work against an even stronger opponent, the USSR. It seems that the view of China as a 'strategic competitor' may have been reduced over the last decade (Bei 2001; Quinlan 2002), but have been resurrected in the last few years as China's diplomatic and military leverage seem to have increased in the wider Asia-Pacific through 2003-2005). Here, simplistic lessons from the past may have dangerous implications, including a possible round of military re-armament in the region, as well as regional diplomatic competition. Rather different lessons seem to have developed in the prospects for a strengthening India as a regional nuclear power, with the US and China moving to cautiously accommodate this new reality, though serious concerns over nuclear proliferation remain even as India moves to provide greater safety of its nuclear power programs (for these issues and the Convention on Nuclear Safety, see Tellis 2002; Xinhua 2005a; Nason 2005). US policy here through 2000-2005 may be simple power-balancing, or a more powerful concept of tiered multipolarity where new powers are allowed to emerge so long as they are partially incorporated in a network of IGOs and do not directly threat US-coalition dominance (Ferguson 2003). Other thinkers have taken the lessons from world wars and global competition in the military arena and simply applied them to the economic arena. Thus, visions of intensified competition in trade, investment and fiscal flows have led to efforts to increase trade and reduce the negative impact of trade deficits, debt default, market collapse, liquidity squeezes, and currency crises. This loose pattern of governance now partly run through several institutional arrangements such as GATT, WTO, the IMF, and the Bank of International Settlements, BIS (see Roberts 1998; Spence 2004). In spite of reform of the IMF, World Bank and BIS through 1998-2005, and the efforts of the G8 (2002-2005) and the United Nations International Conference on Financing for Development (March 2002) it is not certain that even with increased resources that these institutions can ensure national, regional and global financial stability due to the increase flow and speed of financial networks in the 21st century (see lecture 6). Countries such as India and China, precisely because of their growing economic strength, are viewed as sources of future threat but are themselves threatened by growing needs that can only be sustained by an international agenda. In this context, it is true that there now exists greater competition for strategic resources such as oil, gas (e.g. in the Persian Gulf, Caspian Sea region, South China Sea, as well as specific pressures on Nigeria and Venezuela), fisheries, and even over control of river waters, as in the case of Syria and Turkey.). Likewise, hot conflicts over resources might subject victors to penalties that might make resource extraction much less profitable (see Klare 2002), but elsewhere resource conflicts over diamonds, timber and to some degree oil have heightened internal conflicts, e.g in Sierra Leone, Angola, and Nigeria (Le Billon 2005). In the long run, however, there may be a nexus between resource conflict, poor environmental protection, and reduced human security. Week 12 4 Likewise, competitive advantages can be gained through leverage applied through groups such as the WTO for those countries better suited to work with these institutional norms, e.g. tensions between Indian and the U.S. and China and the U.S. over trade liberalisation, piracy and non-tariff barriers. This can be viewed as a kind of 'war of norms' (Bell 2000) in which affluent countries deeply engaged in the international system since the end of World War II have a distinct advantage over poorer or less involved states. A wider, more diffuse conflict between the 'North and South' has been waged, first over issues of fair economic development and debt relief, but now over issues connected with protecting the environment, and fair trade and investment policies. Likewise, globalisation managed 'from above' by advanced nations and strong institutions has begun to be challenged by organised solidarity 'from below' which demands a say in how the life of local communities is managed (see Herod et al. 1997; Brecher et al. 2002). Globalisation, then, has become a highly contested area in terms of both economics, cultural commodities and human rights in the broader sense (see Stiglitz 2002). What has begun to emerge from these analyses is that trade and economics does not always have to be played out in a zero-sum game (I win, you lose), but can take a wide variety of forms, including mutual wins in a growing world economy with strong legal regulation (positive-sum or win-win games). However, wider cross-impacts and the issues of accountability and responsible for negative impacts (on the poor, vulnerable local communities and the environment) have not yet been consistently allocated in the current pattern of global governance (see lectures 5, 6, 8, 11). The realist paradigm has also been 'ported across' into the area of culture and religion. Here cultures, civilisations, and religious are viewed as potential causes of conflict and for intensifying regional wars along fracture lines, e.g. in former Yugoslavia with its religious divides, the Middle East and South Asia (see lecture 4; Huntington 1993; Huntington 1996). As we have seen, there are some exaggerations to this claim, especially since cultures are adaptive, and civilisations and religions can engage in productive dialogue and mutual cross-fertilisation (see Küng 1997; Küng 1991; Ahluwalia & Mayer 1994). Culture is important, including differences between various strategic cultures, but once again their interaction cannot be viewed accurately through the narrow conceptions of game theory or zero-sum games. Attempts to invoke new 'crusades' or 'jihads' are hard to sustain and not very credible in the modern period, even with the heightening over tensions since through 2001-2005. However, these tensions have been sustained by continued patterns of highprofile violence, attendant security clamp-downs (e.g. in the US, UK, France, and to a lesser extent Australia), and distrust of religious ideology. The down-side of this may be more marginalisation for Islamic communities and the further collapse of multiculturalism as a viable option in countries such as the UK and Australia. Putting these issues another way, although the lessons of war and competition are important, they are not the only lessons which can be learned from the events of the twentieth century. Crisis management 'after the fact' has been one way that institutions have adapted to deal with conflict, ranging from military containment, coercive diplomacy, to long-term sanctions. Fortunately, these types of lessons have been useful, but have been complemented by a wider range of options which are Week 12 5 proactive as well as reactive. New ideas drawn from 'the new institutionalism', from constructivism, from cultural and strategic studies, and cosmopolitan theories of governance (see lecture 11) have begun to suggest the way the international system is shaped by patterns of engagement among organisations and creative human activity (see Herod et al. 1997; Henderson 1998; Hudson 1997; Hasselbladh 2000; Narine 1998). Here, some realist theories have been adapted quite effectively to incorporate IGOs, NGOs, international civil movements, and an extension of the notion of power into areas of dialogue, persuasion, and institutional building. We can see this clearly in a couple of examples. 2. Adaptive Change in Strategic Thought: From Human Security Towards Humane Governance We can see two aspects of adaptive change in the serious effort to widen notions of security from a purely military focus to include a much wider range of threats and problems which seem more common for many nations in the late 20th century. Alongside this, there has been an effort to humanise, and to a lesser degree democratise, globalisation trends and flows. Comprehensive security involves a more inclusive and wider adaptation of traditional patterns of strategic thought to the current international climate. There has recently been considerable interest in redefining security, strategic and defensive doctrines to be more inclusive than the past consideration of straightforward military concerns. In large measure, this is due to the recognition that military power, by itself, is unable to secure the fundamental purposes of defence (Cheeseman 1988). This has been clearly demonstrated in terms of international terrorism, transnational security challenges, and fundamental problems in the international order which cannot be managed by single nations. Therefore, comprehensive security includes issues of adequate resource security, access to needed trade routes, cooperative relations among states, and protection of the environment (Dickens 1997). Comprehensive security in new forms has been deployed by the EU, NATO, Japan and China. In the case of China, it has supported a string move towards multilateral regional politics in East Asia, a major shift in policy through 1997-2005 (see Kuik 2005). Likewise, there has been a renewed emphasis on human security, i.e. of individuals, families, local communities and indigenous groups, in the face of a wide range of threats, e.g. natural disasters, environmental collapse, poverty, and warfare (for case studies, see Lizee 2002). Human security has formed a major part of recent Canadian and Norwegian foreign policy, as well as forming a central aspect of debates within the UNDP, the United Nations Development Program (Axworthy 1999; Axworthy & Vollebaek 1998). Though no single definition of human security has been accepted, this shift of interpretation has given a renewed emphasis to humanitarian concerns and the protection of the weak within the international system, and put some pressure on IGOs such as ASEAN, the OSCE, and the OAS (Organisation of American States). Likewise, it requires a concern for human rights, community stability, and proper economic development within a secure environment (see lecture 3). At the same time, it has become recognised that humanitarian intervention (whether in Somalia, Bosnia, East Timor or Kosovo) is an extremely complex, expensive and risky procedure. This is especially the case when it is unauthorised by clearly UNSC Week 12 6 resolutions and clear mobilisation of international law, a factor complicated by nonstate actors (including guerrilla groups, criminal networks, and terrorists organisations). New research in human security in particular tries to find ways to reconcile global, regional, national and human levels of security with the minimum of destructive conflict (see Henk 2005; Bidwai 1999; Magno 1997). In particular, overly weak or aggressively strong governments can in fact reduce the security of their citizens, neighbouring populations and even strong states in the international system. In part, this broadening of the notion of security has been a direct result of events and changing international environments in the 1980's and 1990's (Maik 1992c) and a redefinition of the nature of national power. National power is selectively enhanced or restricted by regional and international organisations. The trend towards regionalism and regionalisation is significant, and is in general more likely to reduce rather than increase hot conflicts, e.g. moderations of conflict through organisations such as ASEAN, the ARF (ASEAN Regional Forum) and APEC, and the reduction of conflict through expanding European Union structures that have engaged in active dialogue with Russia and the Ukraine. This type of cooperative security need not be based on deep integration (as in the EU and NATO), but can be based on looser type of regionalism, called 'soft regionalism': This cooperative approach can be termed 'soft governance'. It has greater utility in providing a way forward than that of 'soft regionalism', which often infers a loose, informal integration centred on consensus as in the ASEAN system, but in the wider Asia-Pacific setting may allow strong external influence by economic powers, e.g. Japanese or Chinese economic networks. 'Soft regionalism' also implies very limited mechanisms for establishing norms, and in the case of the Asia-Pacific groupings can be marred by real cultural differences between Asia and North America, as well as by gaps between rich and poor nations in Asia. 'Soft governance' can, moreover, be viewed as the application of 'soft' power within a regional or multilateral setting. That such governance is not an idealistic and impractical construct can be seen through the considerable progress of ASEAN and the ARF down to mid-1997, the ability of a number of international actors to cope with the Mexican economic crisis of 1994-1995, and the renewed effort by ASEAN and APEC to adapt to global challenges through 1998-2001. Such patterns of 'soft' cooperation remain important because of the need to continue nation-building without generating threat perceptions. (Ferguson 2001). We can assess some of these changes by briefly looking at some of the areas where environmental, human development and national security concerns have begun to interact (see Stern 1995; Hassan 1991; Pirages 1991; Westing 1989). We can illustrate these themes by briefly listing some of the environment and resource issues which are directly impacting on national security and international stability: Week 12 Pollution with related health and climate impact causing international tensions, e.g. between Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia during the repeated great fires that have caused sustained regional air pollution (1997-2000), and over coal-based air pollution among China, South Korea and Japan (Dupont 1998, pp11-14). The estimated cost of the Indonesian bush-fires to regional countries in terms of health, tourism and agricultural losses for 1998 is in the order of 6 billion dollars (Dupont 1998, p12). In wider settings, ongoing deficits in environmental spending and remediation may set future limits on growth 7 in PRC, India and Southeast Asia, as well as set agricultural limits for Australia and parts of Central Asia. At the level of international climate politics, the Kyoto Protocol and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) are at best a limited success in spite of coming into force through 2004-205 (see lecture 7). Future agreements will need bring on board developing countries into emission targets (planned for negotiation towards commitments through 2013-2017). The US has since floated the idea of a new, technology-based approach, the Asia-Pacific Clean Development and Climate Partnership, to reduce carbon emissions, trying to set up dialogue among the US, Australia, India, China, South Korea and Japan. However, it is not clear that this would merely undermine the Kyoto Protocol, and no clear targets have been set in the new agreement (Hodge & Uren 2005) Water and soil pollution directly attacking the food chain, and undermining agriculture, as well as riverine and marine fisheries, as has occured in parts of China, Vietnam, the Philippines and India (Dupont 1998, p15). In the broader context food security has not been confirmed for parts of Africa through (e.g. Niger, Sudan, Ethiopia, Malawi), while under-nourishment remains a real problem for poor communities in South Asia, parts of Latin America, and wartorn or crisis areas. In this context, poverty remains a major debating point, with diverse views on whether globalisation has reduced or intensified this problem. Depending on your definition, 1 or 2 billion people remain in real poverty globally, with real differences between these projections. Although the Millennium Development Goals and the G8 have tried to get some leverage on this problem, poverty seem entwined with security, political and environmental problems that make it hard to tackle unless systematic and sustained effort at different levels is applied to the problem over the next two decades. The problem and related goals have been established as an aim with voluntary targets through major conferences through 1992-2003: Environment, food security, poverty, and land degradation were brought together in three major international documents: Agenda 21 (UNCED 1992), the UN Millennium declaration (UN 2000), and the Plan of implementation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development (UN 2003). Agenda 21 is one of the most balanced and cogently argued of all international documents. As compared with the Stockholm meeting 20 years earlier which focused on pollution, Agenda 21 gives equal place to development, and hence to the environment as a productive resource. This meeting also drew wider attention to the concept of sustainable development, in particular, the conservation of natural resources for use by future generations. The Millennium declaration listed nine Millennium Goals, the first of which was 'Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger' and the seventh, 'Ensure environmental sustainability' (UN 2000 2004). The World Summit on Sustainable Development (Johannesburg, 2002) took Agenda 21 as its starting point and produced a Plan of implementation (UNCED 2003). Sustainability became the key, with emphasis on protecting and managing the natural resource base of economic and social development and recognition of the linkages between poverty, the environment and the use of natural resources. A welcome feature is its recognition that agriculture plays a crucial role in addressing the needs of a growing global population, and is inextricably linked to poverty eradication. The targets of halving the numbers suffering from hunger and poverty are repeated, with a target date of 2015, adding an objective of halving the numbers without access to safe drinking water. Again, however, in the outputs of this Summit, the UN forecasts of population increases in the developing world are taken as background, given, data. (Young 2005) Week 12 8 A boom in the demand for energy generally, with very strong trends in the Asia-Pacific, which will intensify disputes over gas and oil reserves, especially in disputed areas (Dupont 1998, pp25-35). It must be noted that East Asian countries usually have petroleum and gas energy stocks of only around 40 days (20 days for China) of domestic use (Dupont 1998, pp29-30). Long-term demands for increased gas and oil are a major part of PRC national planning (see Chang 2001). Although Indonesia and China could dig deeper into their own underground reserves, for countries such as Japan and South Korea, a simple loss of petroleum and gas imports over a 20-40 day period would result in a major international crisis. More generally, even countries with strong energy access such as the US and Russia have sought to use low prices and easy access to boost their economies and increase political domestic stability. In this context it is possible to argue that countries as diverse as Iraq, Iran, and Nigeria have suffered from a resource curse, i.e. strong resources that become the basis of either international interference or over-dependence on a narrow economic structure that relies on international markets (see Le Billon 2005). Basic requirements in the international system are often not well managed. Soil fertility in intensive settings, sustainable agriculture, waste management, megacities cities in the developing world, access to basic infrastructure remain uncertain for up to one third of the planet (see lecture 1, 7, 9). Fresh water, traditionally a renewable resource, is now in heavily increased demand for use by urban populations, for agriculture, and in industrial processes, leading to decreased availability of clean water globally, and in Asia-Pacific particularly (Dupont 1998, p59-74). Water disputes have intensified tensions in the Jordan River basin, the Nile and Euphrates river systems in the Middle East, and water issues in South Asia and the Mekong River have to be carefully managed to avoid such disputes in the future (Thapliyal 1996; see lecture 1). It has been suggested that by the 2025, up to two thirds of the world's population will be under conditions of 'water stress' (Dupont 1998, p59) due to lack of clean and reliable water supplies. It is not surprising, on this basis, that there is a direct link among poverty, slow development and a lack of human security. Using a compound indicator such as the 'index of human insecurity' (using a range of economic, environmental, social and institutional factors) it is possible to map this against a variable reflecting the rounded quality of life summarised by the Human Development Index (commonly used in UN institutions). This yields the un-surprising fact that a low level of development equates generally with a lack of human security, though crises or short-term conflicts can complicate this picture (see Lonergan et al. 2000). Week 12 9 (from Lonergan et al. 2000) In summary, global governance trends suggest a n effort to set the standards to humanise globalisation, but serious gaps remain in the most basic factors of human development, human security, and access to basic resource needs. 3. Diversifying Pragmatism in the 21st Century Another key aspect thought about the global system over the last decade has been the ability to include (sometimes reluctantly) a wider range of alternative patterns of thinking and institutional alternatives than before. In large measure, this response has been due to the fact that international and transnational forces are much stronger than before, and are beginning to create a truly global pattern of interdependence, as well as strong flows of wealth, information and contact that run alongside or around inter-national linkages. Likewise, the powers of the state seem to have been in many ways eroded, making the state a still important but more disturbed actor in the global system (Sørensen 1996). Some of these alternative patterns include: Week 12 The 'Realism Against Idealism debate' vs Responsible Global Politics (Küng 1997, pp1-90). International Anarchy vs Internationalism and an emerging International Society of not yet a Global Community (See Henderson 1998; Iriye 1997). Cultural differences as a source of conflict (Huntington 1993; Huntington 1996) vs cultural differences as a resource of diversity and problem solving. 10 Extractive Economies vs Sustainable Economies (weak or strong sustainability). Traditional Economic and Financial Systems vs the need for Global Financial Reform, plus added patterns of financial activity including Islamic Banking, Grameen Banking, Micro-loan Schemes, and small community business initiatives. These schemes augment rather than replace tradition banking and investment arrangements. Normative Globalisation verses 'Planetisation' (positive future visions of global order), 'balanced globalism' and 'cosmopolitanism', whereby pluralist ideas are beginning to shape international networks of ideas and expectations (see lecture 11; for a recent spin on this see, Smyth 2001). The State as the main International Actor vs a range of multi-level actors, e.g. local communities, cities (megacities, World Cities, sister cities), corporations, INGOs, IGOs, regional groupings, global level organisations (Sørensen 1996). Revolutionary change vs Strategic Non-violent Action or Low-Violent People Power, combined with transnational mobilisation strategies (see lecture 11). The need to re-balance and fine tune global institutions to achieve a better balance of international justice. As noted by Amartya Sen: The central issue of contention is not globalization itself, nor is it the use of the market as an institution, but the inequity in the overall balance of institutional arrangements which produces very unequal sharing of the benefits of globalization. The question is not just whether the poor, too, gain something from globalization, but whether they get a fair share and a fair opportunity. There is an urgent need for reforming institutional arrangements-in addition to national ones--in order to overcome both the errors of omission and those of commission that tend to give the poor across the world such limited opportunities. Globalization deserves a reasoned defense, but it also needs reform. (Sen 2002) In a sense, then, people, organisations and governments are being offered a much wider range of tools, resources and organisations for creative, low-violent change in the current century. These tools and institutions allow us to think about the international system in diverse ways, engage and participate in change even if on a modest scale, and to be aware of a much wider ambit of the dynamic transformations that are occurring. It is crucial that such change be pursued and further developed if a positive and sustainable global system is to emerge in the following decades. At present, the global system is far from complete, and seems to be a non-convergent, contested mix of power and cooperative orientations. This may be due to ongoing transitions, or because the global network of governance has not yet been completely built or linked together. Week 12 11 Human Insecurity Remains A Crucial Problem Globally (from Lonergan et al. 2000) It might be worthwhile to give one last example of this wider, inclusive strategy of thinking about diversity. Religious differences have sometimes been presented as a major source of conflict, e.g. in Ireland, the Middle East, and South Asia. There is, of course, some truth to this, especially when religion is used as an excuse to ignore the claims of others, and used as a pretext for violence. However, most often it is the misunderstanding of religion which intensifies conflict and deepens disaster. Hans Küng has demonstrated this clearly in assessing the supposed role of religion in the Yugoslavian conflict. One of the problems in modern international relations analysis is that often religion is not taken seriously enough, due to a 'secularizing reductivism' which sees only material issues of power as worth noting (Küng 1997, p120). Küng notes that in the 1980s no serious analysis of ethnic and religious differences in Yugoslavia was made in foreign affairs offices in Germany or France, nor in London or Washington (Küng 1997, p122). As a result, several phases of erroneous policies were made in relation to the ethnic crisis in Yugoslavia (Küng 1997, pp122-124): The first error, made by the EU, UN and U.S. was to try to insist that some form of unified Yugoslavian state was the best option. The second error was a phase of different recognition of small sovereign states by other states without the means to protect these newcomers. Germany recognised Croatia and Slovenia at an early date, as did the Vatican, regarding Croatia as a 'bulwark of (Western) Christianity' (Küng 1997, p123). Phase 3 allowed the drawing of arbitrary borders to create a settlement in Bosnia, thereby effectively rewarding Serbian (and Croatian) aggression in the region (Küng 1997, p124). Küng goes on to show that all the Churches in the region also failed to back up the idea of peace, and only tried to build reconciliation with Muslim groups when events had already seriously deteriorated (Küng 1997, p126). Put frankly, it was not so much religion, as a misuse of religion and the reluctance of the international community to chart a path for low violent reform that failed to avoid the holocaust in the Week 12 12 Balkans. In the current period, it is crucial that blockages in dialogue do not create a similar set of incorrect signals in relation to Islam at the global level. These considerations should not lead us to a complacent optimism. Such opportunities should be grasped to avoid much greater problems in the future, while a wide range of global problems have indeed not been solved and remain deeply problematic (see above). Moreover, misunderstanding these key issues and not grasping available tools will only tend to deepen such conflicts, reducing the political will to look for ways to manage problems. To date, fairly simplistic and naive interpretations of international relations, parading under the respectable titles of 'political realism', 'economic rationalism' or 'humanitarian idealism', have helped create problems as much as solve them. A new pragmatism, relying on a wide range of viewpoints, tools and actors, is needed to complement the insights of a more genuine realism that grasps the conditions of the 21st century. 4. Bibliography and Further Reading Resources The International Labour Organization is 'the UN specialized agency which seeks the promotion of social justice and internationally recognized human and labour rights. It was founded in 1919 and is the only surviving major creation of the Treaty of Versailles which brought the League of Nations into being and it became the first specialized agency of the UN in 1946.' See http://www.ilo.org/ The International Network for Environment and Security has a range of interesting publications, links and bibliographies that can be found at http://www.gechs.org/INES/ineshome.shtml A wide range of Open Access Journals can be found at www.doaj.org (IR related journals will be found under the Social Sciences and Sociology subheadings.) The Carnegie Council has some interesting perspectives on Global Policy Initiatives, Poverty, and Democratising Globalisation via http://www.policyinnovations.org/ The Global Policy Forum is a web-based resource with critical commentary on major international actors, including the UNSC, NGO's and the US on the basis of increasing accountability. Located at http://www.globalpolicy.org/ Further Reading SEN, Amartya " How to judge globalism: global links have spread knowledge and raised average living standards. But the present version of globalism needlessly harms the world's poorest", The American Prospect, 13 no. 1, January 1, 2002, pA2-7 [Internet Access via Infotrac Database] BRECHER, Jeremy et al. Globalization from Below, The Power of Solidarity, Cambridge, South End Press, 2002 CASE, William "Sayonara to the Strong State: From Government to Governance in the Asia-Pacific", in MAIDMENT, Richard, GOLDBLATT, David & Week 12 13 MITCHELL, Jeremy (eds.) Governance in the Asia-Pacific, London, Routledge, 1998, pp250-274 HENK, Dan "Human security: relevance and implications", Parameters, 35 no. 2, Summer 2005, pp91-106 [Access via Infotrac Database] KLARE, Michael Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict, N.Y., Henry Holt and Company, 2002 KUIK, Cheng-Chwee "Multilateralism in China's ASEAN policy: its evolution, characteristics, and aspiration", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 27 no. 1, April 2005, pp102-123 [Access via Infotrac Database] LE BILLON, Philippe Fuelling War: Natural Resources and Armed Conflict, London, IISS, Adelphi Paper 373, 2005 LIZEE, P. " Human Security in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 24 no. 3, December 2002, pp509-537 [Access via Infotrac Database] Scenarios for the Future of United States-China Relations 2001-2010, Nautilus Institute, 2000 [Available in PDF format at http://www.nautilus.org/enviro/scenarios.html] Bibliography AHLUWALIA, Pal & MAYER, Peter "Clash of Civilisations - or Balderdash of Scholars?", Asian Studies Review, 18 no. 1, 1994, pp21-30 ALAGAPPA, Muthiah (ed.) Political Legitimacy in Southeast Asia, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 1995 ANDERSON, Benedict The Spectre of Comparison: Politics, Culture and the Nation, London, Verso, 1998 ANTLOV, Hans & NGO, Tak-Wing The Cultural Construction of Politics in Asia, Richard, Curzon Press, 1997 AXWORTHY, Lloyd Human Security: Safety for People in a Changing World, Concept Paper, The Canadian Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 29 April 1999 [[Internet Access at http://www.dfait-maeci.gc.ca/foreignnp/HumanSecurity/secur-e.htm] AXWORTHY, Lloyd & VOLLEBAEK, Knut "Now for a New Diplomacy to Fashion a Humane Work", Herald International Tribune, 21 October 1998 [Internet Access at http://www.dfaitmaeci.gc.ca/foreignnp/HumanSecurity/tribu-e.htm] BEI, Xin "Positive Step to Build Warmer Ties", China Daily, 2 August 2001 [Internet Access] BELL, Coral "Changing the Rules of International Politics", AUS-CSCAP Newsletter no. 9, February 2000 [Internet Access at http://aus-cscap.anu.edu/Auscnws9.html] BETTS, Tom "Energy and Security: A Retrospective Analysis of the Energy Policies of the United States and Japan", Culture Mandala: The Bulletin for the Centre of East-West Economic and Cultural Studies, no. 2, 1995 BIDWAI, Praful "Towards a New Paradigm: Comprehensive Security, Weapons of Mass Destruction, and Biological Weapons", Politics and Life Sciences, 18 no. 1, March 1999, pp109-111 BOUCHON, Genevieve & MANGUIN, Pierre-Yves (eds.) Asian Trade and Civilisation, Cambridge, CUP, 1997 BRECHER, Jeremy et al. Globalization from Below, The Power of Solidarity, Cambridge, South End Press, 2002 CAMROUX, David & DOMENACH, Jeab-Luc (eds.) Imagining Asia: The Construction of an Asian Regional Identity, London, Routledge, 1998 CAUQUELIN, Josiane et al. Asian Values: Encounter with Diversity, Richmond, Curzon Press, 1998 CHANG, Felix K. "Chinese Energy and Asian Security", Orbis, Spring 2001 [Internet Access via http://www.findarticles.com] CHEESEMAN, Graeme The Application of the Principles of Non-Offensive Defence Beyond Europe: Some Preliminary Observations, Canberra, ANU Peace Research Centre, Working Paper no. 78, April 1990 CHEESEMAN, Graeme Alternative Defence Srategies and Australia's Defence, Canberra, Australian National University Peace Research Centre, Working Paper no. 51, September 1988 Week 12 14 CHELLANY, Brahma “Nuclear Weapons and India in Asia”, Paper presented at the India Looks East Workshop, Australian National University, December 5-6, 1994 CHELLANY, Brahma “After the Tests: India’s Options”, Survival, 40 no. 4, Winter 1998-1999, pp93111 CHEN, Edward & HUNG, Kwan Chu (eds.) Asia’s Borderless Economy, North Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1997 CREEL, Herrlee G. The Origins of Statecraft in China: Volume I, The Western Chou Empire, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1970 DAALDER, Ivo H. "'He's Gone' - The End of the Milosevic Era", San Diego Union Tribune, 15 October 2000 [Internet Access via http://www.brook.edu/] DELLIOS, Rosita "China-United States Relations: The New Superpower Politics", The Culture Mandala, 3 no. 2, August 1999, pp1-20 DESJARDINS, Marie-France Rethinking Confidence-Building Measures: Obstacles to Agreement and the Risks of Overselling the Process, London, IISS, Adelphi Paper 307, 1996 DICKENS, David (ed.) No Better Alternative: Towards Comprehensive and Cooperative Security in the Asia Pacific, Wellington, Centre for Strategic Studies New Zealand, 1997 DREYER, June Teufel "Multiculturalism in History: China, the Monocultural Paradigm", Orbis, Fall 1999 [Access via www.findarticles.com] DUPONT, Alan The Environment and Security in Pacific Asia, London, IISS, Adelphi Paper 319, 1998 FARRAR, Cynthia The Origins of Democratic Thinking, Cambridge, CUP, 1988 FERGUSON, R. James "New Forms of Southeast Asian Regional Governance: From 'Codes of Conduct' to 'Greater East Asia'", Non-Traditional Security Issues in Southeast Asia, Singapore, Select Publishing and the Institute of Defence and Strategic Studies, 2001, pp122-165 FERGUSON, R. James "India, Multipolarity and Contested Globalisation", in ROY, K. (ed.) Small and mid-Great Powers in Southern Hemisphere and their Relations with Northern Neighbours, New Delhi, Atlantic Publishers, 2003, pp114-157 FORLAND, Tor Egil "The History of Economic Warfare: International Law, Effectiveness, Strategies", Journal of Peace Research, 30 no. 2, 1993, pp151-162 FREEDMAN, Lawrence The Revolution in Strategic Affairs, London, IISS, Adelphi Paper 318, 1998 FUKUYAMA, Francis The End of History and the Last Man, London, Penguin, 1992 FUNABASHI, Yoichi "The Asianization of Asia", Foreign Affairs, 72 no. 5, November/December 1993, pp75-85 (Vertical File) GELLNER, Ernest Conditions of Liberty: Civil Society and its Rivals, London, Hamish Hamilton, 1994 GHOSHROY, Subrata "Not a Catastrophe: Another Look at the South Asian Nuclear Tests", Arms Control Today, 29 no. 8, December 1999 [Internet Access via Proquest] GILL, Ranjit Under Siege: How the Asian Miracle Went Wrong, Kuala Lumpur, Management Services, 1998 HARRIS, Stuart "The Economic Aspects of Pacific Security", Adelphi Paper 275, Conference Papers: Asia's International Role in the Post-Cold War Era, Part I, (Papers from the 34th Annual Conference of the IISS held in Seoul, South Korea, from 9-12 September 1992), March 1993, pp14-30 HASS, Peter M. "International institutions and social learning in the management of global environmental risks", Policy Studies Journal, 28 no. 3, 2000, pp558-575 HASSELBLADH, Hans "The Project of Rationalization: A Critique and Reappraisal of NeoInstitutionalism in Organization Studies", Organizational Studies, July 2000 [Internet Access via www.findarticles.com] HASSAN, Shaukat Environmental Issues and Security in South Asia, London, IISS, Adelphi Paper 262, Autumn 1991 HEFNER, Robert W. Market Cultures: Society and Values in the New Asian Capitalisms, Singapore, ISEAS, 1997 HEISBOURG, Francois “The Prospects for Nuclear Stability Between India and Pakistan”, Survival, 40 no. 4, Winter 1998-1999, pp77-92 HENDERSON, Conway International Relations: Conflict and Cooperation at the Turn of the 21 st Century, Boston, McGrawHill, 1998 HENK, Dan "Human security: relevance and implications", Parameters, 35 no. 2, Summer 2005, pp91106 [Access via Infotrac Database] Week 12 15 HEROD, Andrew, TUATHAIL, Gearóid & ROBERTS, Susan M. (eds.) An Unruly World?: Globalization, Governance and Geography, London, Routledge, 1998 HEWITT, Vernon "Containing Shiva? India, Non-Proliferation, and the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty", Contemporary South Asia, 9 no. 1, March 2000 [Internet Access via Proquest] HIGGINS, Alexander G. "Oil Ministers Agree to Stabilization", Excite news, 29 July 2001 [Internet Access] HODGE, Amanda & UREN, David "Strangling the Son of Kyoto", Weekend Australian, July 30-31wt 2005, pp1-2 HUDSON, Valerie M. (ed.) Culture and Foreign Policy, Boulder, Lynne Rienner, 1997 HUNTINGTON, Samuel P. “The Clash of Civilizations?”, Foreign Affairs, Summer 1993, pp22-49 HUNTINGTON, Samuel P. The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, N.Y., Simon & Schuster, 1996 HUTCHINGS, Graham "Time of the Hungary Dragon", Sunday Mail, June 11, 1995, p59 IRIYE, Akira Cultural Internationalism and World Order, N.Y., John Hopkins University Press, 1997 JAE-HYUNG "China's Expanding Maritime Ambitions in the Western Pacific", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 24 no. 3, December 2002, pp549-568 [Access via Infotrac Database] JOECK, Neil Maintaining Nuclear Stability in South Asia, London, IISS, Adelphi Paper 312, 1997 KAHN, Joel S. (ed.) Southeast Asian Identities: Culture and the Politics of Representation, Singapore, ISEAS, 1998 KLARE, Michael Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict, N.Y., Henry Holt and Company, 2002 KUIK, Cheng-Chwee "Multilateralism in China's ASEAN policy: its evolution, characteristics, and aspiration", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 27 no. 1, April 2005, pp102-123 [Access via Infotrac Database] KÜNG, Hans A Global Ethic for Global Politics and Economics, London, SCM Press, 1997 KÜNG, Hans Global Responsibility: In Search of a New World Ethic, N.Y., Crossroads, 1991 LAPID, Yosef & KRATOCHWIL, Friedrich (eds.) The Return of Culture and Identity in IR Theory, London, Lynne Rienner, 1996 LE BILLON, Philippe Fuelling War: Natural Resources and Armed Conflict, London, IISS, Adelphi Paper 373, 2005 LEPOR, Keith Philip (ed.) After The Cold War: Essays on the Emerging World Order, Austin, Texas, 1997 LESBIREL, S.H. "The Political Economy of Substitution Policy: Japan's Response to Lower Oil Prices", Pacific Affairs, 61 no. 2, 1988 LIZEE, P. " Human Security in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia", Contemporary Southeast Asia, 24 no. 3, December 2002, pp509-537 [Access via Infotrac Database] LONERGAN, Steve et al. "The Index of Human Insecurity", AVISO, no. 6, January 2000 [Internet Access at http://www.gechs.org/aviso/avisoenglish/six_lg.shtml] MACK, Andrew Alternative Defence Concepts: The European Debate, Canberra, ANU Peace Research Centre, Working Paper no. 68, May 1989 MACK, Andrew Defence Versus Offence: The Dibb Report and Its Critics, Canberra, Australian National University Peace Research Centre, Working Paper no. 14, September 1986 MAGNO, Francisco A. "Environmental Security in the South China Sea", Security Dialogue, 28 no. 1, March 1997, pp97-112 MALIK, J. Mohan et al. Asian Defence Policies: Great Powers and Regional Powers (Book I), Geelong, Deaking University Press, 1992a MALIK, J. Mohan "India" in MALIK, J. Mohan et al. Asian Defence Policies: Great Powers and Regional Powers (Book I), Geelong, Deaking University Press, 1992b, pp142-164 MALIK, J. Mohan "Patterns of Conflict and the Security Environment in the Asia-Pacific Region: the Post - Cold War Era", in MALIK, J. Mohan et al. Asian Defence Policies: Great Powers and Regional Powers (Book I), Geelong, Deaking University Press, 1992c, pp33-52 MALIK, Mohan “Sino-Indian Relations and India’s Eastern Strategy”, Paper presented at the India Looks East workshop, Australian National University, December 5-6, 1994 MALIK, Mohan “India Goes Nuclear: Rationale, Benefits, Costs and Implications”, Contemporary Southeast Asia, 20 no. 2, August 1998, pp191-215 MILIVOJEVIC, Marko "The Spratly and Paracel Islands Conflict", Survival, 31 no. 1, January/February 1989, pp70-78 Week 12 16 MORGANTHAU, H.J. Politics Amongst Nations: The Struggle for Power and Peace, N.Y., Knopf, 1985 NARINE, Shaun "Institutional theory and southeast Asia: the case of ASEAN", World Affairs, Summer 1998 [Access via www.findarticles.com] NASON, David "US Offers Indians Nuclear Power Aid", Australian, 20 July 2005, p9 NATHAN, Andrew J. "Chinese Democracy: The Lessons of Failure", Journal of Contemporary China, No 4, Fall 1993a, pp3-13 NATHAN, Andrew J. "Is Chinese Culture Distinctive?" Journal of Asian Studies, 52 no. 4, November 1993b, pp923-936 NATHAN, Andrew J. & SHI, Tianjian "Cultural Requisites for Democracy in China: Findings from a Survey", Daedalus, Spring, 1993, pp95-123 NOLAND, Marcus et al. "Famine in North Korea: Causes and cures", Economic Development and Cultural Change, 49 no. 4, July 2001, pp741-767 PALMER, Bryan D. "Old Positions/New Necessities: History, Class, and Marxist Metanarrative", in WOOD, Ellen Meiksins et al. (ed.) In Defense of History: Marxism and the Postmodern Agenda, N.Y., Monthly Review Press, 1997, pp65-73 PETTMAN, Ralph Asian Globalism, Paper presented at the ISA/JAIR joint conference, Makuhari, Japan, September 20-22, 1996 (Vertical File) PETTMAN, Ralph International Politics, Boulder, Lynne Rienner, 1991 PIRAGES, D. "Environmental Security and Social Evolution", International Studies Notes, 16 no. 1, 1991, pp8-12 QUINLAN, Joseph P. "Ties That Bind", Foreign Affairs, 81 no. 4, July/August 2002, pp116-126 RICHARDSON, Michael "Spratlys Curtain-Raiser to Global Energy Grab", The Australian, 16 June 1995, p21 ROBERTS, Adams Humanitarian Action in War: Aid Protection and Impartiality in a Policy Vacuum, London, IISS, Adelphi Paper 305, 1996 ROBERTS, Susan M. "Geo-Governance in Trade and Finance and Political Geographies of Dissent", in HEROD, Andrew et al. An Unruly World: Globalization, Governance and Geography, London, Routledge, 1998, pp116-134 ROBINSON, Linda "Towards a Realistic Cuba Policy", Survival, 42 no. 1, Spring 200, pp116-129 SCHELL, Orville "China's Hidden Democratic Legacy", Foreign Affairs, 83 no. 4, July-August 2004 [Access via Infotrac Database] SEGAL, Gerald China Changes Shape: Regionalism and Foreign Policy, London, International Institute for Strategic Studies, Adelphi Paper 287, March 1994 SEGAL, Gerald & GOODMAN, David China Deconstructs: Politics, Trade and Regionalism, London, Routledge, 1994 SEN, Amartya " How to judge globalism: global links have spread knowledge and raised average living standards. But the present version of globalism needlessly harms the world's poorest", The American Prospect, 13 no. 1, January 1, 2002, pA2-7 [Internet Access via Infotrac Database] SEYMOUR, Michael “Ancient Mesopotamia and Modern Iraq in the British Press, 1980-2003”, Current Anthropology, 45 no. 3, June 2004, pp351-368 SINGH, Jasjit "India's Nuclear Doctrine", in SINGH, Jasjit (ed.) Asian Strategic Review 1998-1999, New Delhi, Institute for Defence and Strategic Studies, November 1999, pp9-23 SMYTH, Rosaleen "Mapping US Public Diplomacy in the 21 st Century", Australian Journal of International Affairs, 55 no. 3, November 2001, pp421-444 SØRENSEN, Georg "Individual Security and National Security", Security Dialogue, 27 no. 4, December 1996, pp367-386 SOROS, George On Globalization, N.Y., Public Affairs, 2002 SPENCE, Scott Armstrong "Organizing an arbitration involving an international organization and multiple private parties: the example of the Bank for International Settlements arbitration", Journal of International Arbitration, 21 no. 4, August 2004, pp309-328 [Access via Infotrac Database] STERN, Eric K. "Bringing the Environment In: The Case for Comprehensive Security", Cooperation and Conflict, 30 no. 3, September 1995, pp211-237 STIGLITZ, Joseph Globalization and its Discontents, London, Allen Lane, 2002 SUN, Haichen (trans. & ed.) The Wiles of War: 36 Military Strategies from Ancient China, Beijing, Foreign Languages Press, 1991 SUN, Tzu The Art of War, trans. by Samuel Griffith, Oxford, OUP, 1971 Week 12 17 TELLIS, Ashley J. "The Strategic Implications of a Nuclear India", Orbis, Winter, 2002 [Internet Access via www.findarticles.com] TERRILL, Ross "A Bloc to Promote Freedom", The Australian, 19 July 2005, p13 THAPLIYAL, Sangeeta “Water and Conflict: The South Asian Scenario”, Strategic Analysis, 19 no. 7, 1996, pp1033-1052 THOMAS, Bradford L. The Spratly Islands Imbroglio: A Tangled Web of Conflict, Canberra, Australian National University Peace Research Centre, Working Paper No. 74, April 1990 THUROW, Lester Head to Head: The Coming Economic Battle Among Japan, Europe, and America, Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1992 WESTING, Arthur H., (ed.) Comprehensive Security for the Baltic: An Environmental Approach, Sage Publications, 1989 WALKER, Richard Louis The Multi-State System of Ancient China, Connecticut, The Shoe Strong Press, 1953 WOOD, Ellen Meiksins et al. (ed.) In Defense of History: Marxism and the Postmodern Agenda, N.Y., Monthly Review Press, 1997 World Oil "OPEC learns output management", February 2001 [Internet Access via www.findarticles.com] Xinhua "India ratifies nuclear safety convention", Xinhua News Agency, March 31, 2005a [Access via Infotrac Database] YOUNG, Anthony "Poverty, hunger and population policy: linking Cairo with Johannesburg", The Geographical Journal, 171 no. 1, March 2005, pp83-95 Week 12 18