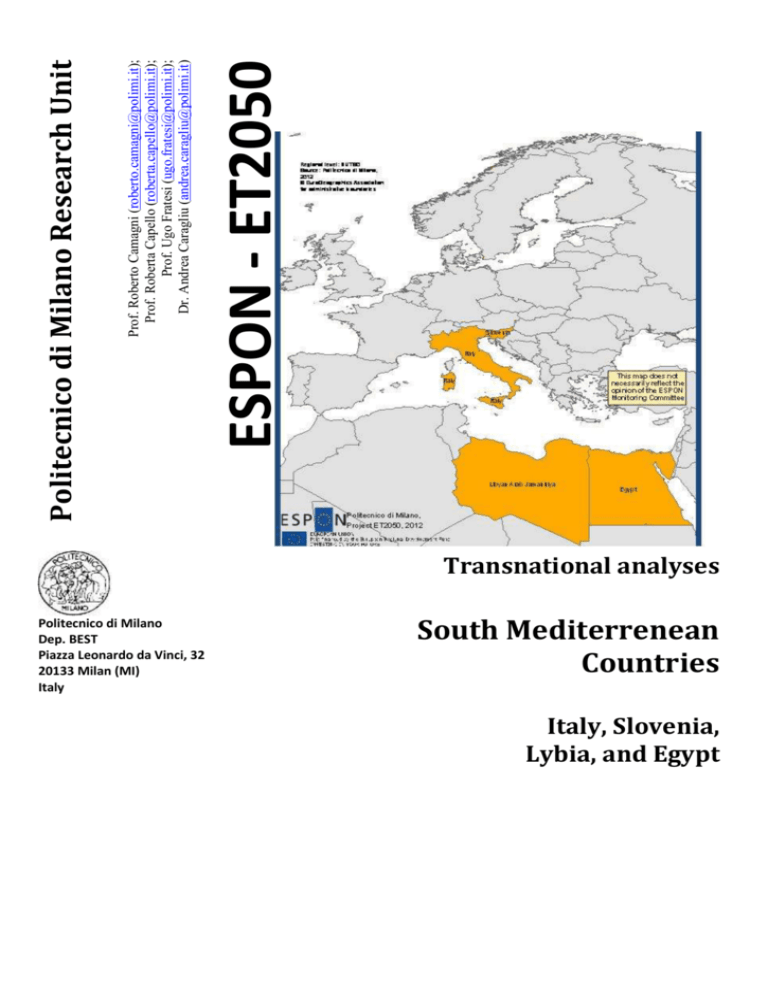

South Mediterranean Region Report by POLIMI (version

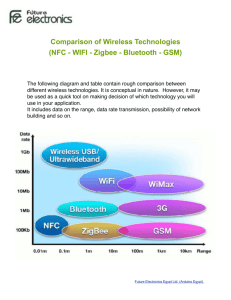

advertisement