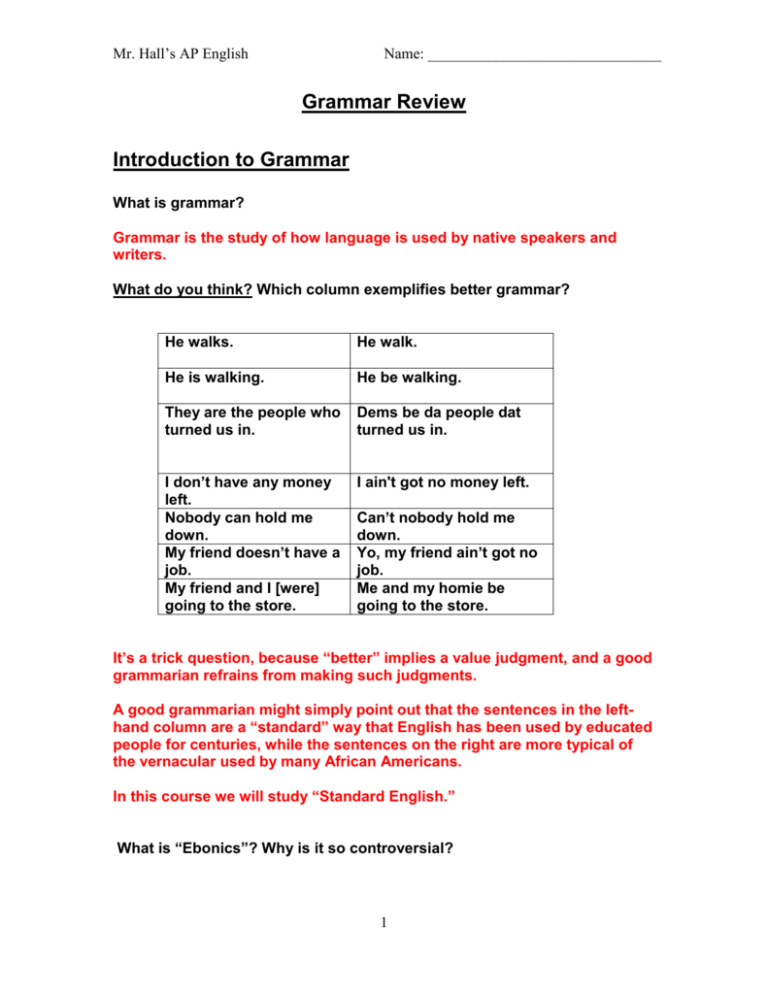

Mr. Hall's Grammar Review

advertisement