Cost of Capital - of [www.mdavis.cox.smu.edu]

advertisement

![Cost of Capital - of [www.mdavis.cox.smu.edu]](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/008952041_1-d815507e779b91930bdfd4a584f3c02a-768x994.png)

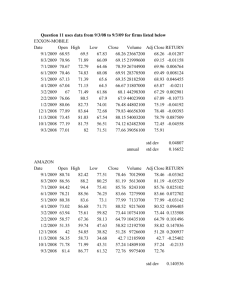

Cost of Capital • The cost of capital is the minimum rate of return an investment project must generate in order to pay its financing costs. • For a levered firm, the financing costs can be represented by the weighted average cost of capital. Weighted Average Cost of Capital = K = (1-)Kl +(1-t)i Where K = weighted average cost of capital Kl = cost of equity capital for a levered firm i = pretax cost of debt = debt to total market value ratio t = marginal corporate tax rate. Remember the question of the optimal capital structure (the appropriate mix of debt and equity) is complicated by issues such as The cost of equity may vary with the capital structure. The deductibility of interest will influence the value of debt Increasing leverage increases the liklihood of bankruptcy. 1 If the firm can lower its cost of capital more investment opportunities become profitable and (assuming the investments are properly analyzed and executed—a big if) raise the value of the firm. But if the capital markets are efficient, the firm can’t do much about its cost of capital (other than make sure the capital structure is optimal). That is, it can’t control Kl or i. If International capital markets don’t function perfectly efficiently, however, then reaching into international markets to raise capital really can be a good idea. This means that the really critical question is whether or not the cost of capital is the same all over the world. 2 Cost of Equity in Segmented and Integrated Markets • • The cost of equity capital (Ke) of a firm is the expected return on the firm’s stock that investors require. This return is frequently estimated using the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM): Ri = Rf + Bi(Rm-Rf) where Ri = the cost of capital for firm i Rf = the risk free rate of return (e.g., the return on Treasury bills) Rm = the return on a diversified portfolio of stock (e.g., the S&P 500) Bi = Covariance(Ri,Rm)/Variance(Rm) The whole idea behind the CAPM is that stockholders, can own a diversified portfolio, they don’t care about the overall level of riskiness associated with a firm’s stock Instead all the care about is the systematic risk—the risk that can’t be eliminated by diversifying. 3 Key Issues in Estimating Discount Rates for Foreign Projects Suppose Starbuck’s is considering expanding into Italy. How would they compute the appropriate cost of capital to use in discounting the expected cash flows? Should the corporate proxy be foreign or domestic? Should they use the example of an Italian coffee company or use the beta implied by the U.S.? Clearly the ideal is to use the beta for that market. In estimating the beta for the foreign coffee shops, Starbucks would like to use a local firm as an example. If that beta is not available, an alternative is to use a beta that is consistent with a closely related industry. But there is nothing like Starbuck’s in Italy. There are however “bars” (sort of combination, coffee shop/7-11/corner pub). If that beta is not available, they might use a beta based on a U.S. proxy adjusted for the foreign country. More specifically, one could compute the foreign market beta (which essentially measures the beta of a portfolio of foreign stocks relative to U.S. stocks). This is Bf = [Correlation with UsxStd Deviation of For]/Std Deviation of US The adjusted beta = BUSproxyxBF If Starbuck’s, U.S. beta = .8 and the Italian beta = .6, the appropriate beta for the Italian subsidiary is .8x.6=.64. Should they look at the beta computed on a proxy beta represented by the domestic, local or the world portfolio? If you believe that capital markets are truly integrated, then the world beta is what matters. However, many would argue that capital markets are not nearly well enough integrated as to permit this and that it is more important that all of a firms 4 projects be judged by the same basic standard. This argues for calculating the foreign beta relative to a domestic porolio. Should the market risk premium be based on the domestic, local or foreign risk premium? If one is using a domestic portfolio, it makes sense to use a domestic market risk premium. How should country risk be included. 5 Applying the CAPM Prior to 1988, the Swiss firm Nestle had two types of stock, registered which could only by owned by Swiss citizens and bearer which could be owned by anyone. The shares had the same basic ownership and dividend rights, but the registered shares were worth much less. After the distinction was eliminated, the value of the registered shares rose by about 33% and the value of the bearer shares fell by about 25%. But the overall equity value of Nestle rose by about 10%. Think about how this is consistent with the CAPM. The Swiss Rf was about 4.6% and the return on a diversified portfolio of Swiss stock was about 9.8%. The Nestle Beta (for a Swiss portfolio) was .9. This implies a cost of equity of 4.6+.90(9.8-4.6) = 9.3% As compared with a portfolio of world-wide stocks, however, Nestle’s beta was only about .6. Given a world risk premium and of 6% and a risk free rate of 4.5%, the cost of equity is 4.5 + 0.6x6 = 8.1% 6 Note on the Cost of Foreign Borrowing If you borrow one unit of the foreign currency, you get S0 units of the domestic currency. If you borrow €100 million when the spot rate is .9, you get $90MYou are obligated to pay (1+rf) units of the foreign currency. If the foreign rate was 7%, you have to repay €107 million. This means you have to repay S1(1+rf) units of the domestic currency. If the euro has fallen to .85, you have to pay $90.95 M This means your effective interest rate was r = (1+rf)S1/S0 You paid an interest rate of 90.95/90 – 1 = 1.06% A little algebra will show that the effective rate was r = c +(1+c)rf Where c is the proportional change in the exchange rate. The exchange rate fell by 5/90=.05556 and so r = -.0556 +(1-.0556)x.07 = 1.06 7 Cross-Border Listings of Stocks • Cross-border listings of stocks have become quite popular among major corporations. • The largest contingent of foreign stocks are listed on the London Stock Exchange. • U.S. exchanges attracted the next largest contingent of foreign stocks. 8 Cross-border listings of stocks benefit a company in the following ways. The company can expand its potential investor base, which will lead to a higher stock price and lower cost of capital. Cross-listing creates a secondary market for the company’s shares, which facilitates raising new capital in foreign markets. Cross-listing can enhance the liquidity of the company’s stock. Cross-listing enhances the visibility of the company’s name and its products in foreign marketplaces. Cross-border listings of stocks do carry costs. It can be costly to meet the disclosure and listing requirements imposed by the foreign exchange and regulatory authorities. Once a company’s stock is traded in overseas markets, there can be volatility spillover from these markets. Once a company’s stock is make available to foreigners, they might acquire a controlling interest and challenge the domestic control of the company. 9 The Effect of Foreign Equity Ownership Restrictions • While companies have incentives to internationalize their ownership structure to lower the cost of capital and increase market share, they may be concerned with the possible loss of corporate control to foreigners. • In some countries, there are legal restrictions on the percentage of a firm that foreigners can own. • These restrictions are imposed as a means of ensuring domestic control of local firms. 10 The Financial Structure of Subsidiaries. • There are three different approaches to determining the subsidiary’s financial structure. • Conform to the parent company's norm. • Conform to the local norm of the country where the subsidiary operates. • Vary judiciously to capitalize on opportunities to lower taxes, reduce financing costs and risk, and take advantage of various market imperfections. • In addition to taxes, political risk should be given due consideration in the choice of a subsidiary’s financial structure. 11 Real After-Tax Cost of Funds 8 6 4 2 0 -2 U.S. UK 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 Source: Robert McCauley and Steven Zimmer, “Exchange Rates and International Differences in the Cost of Capital” in Y. Amihud and R. Levich, Exchange Rates and Corporate Performance (Burr Ridge, Ill; Irwin 1994). 12