Pine Creek Ranch Wildlife Habitat and Watershed Management Plan

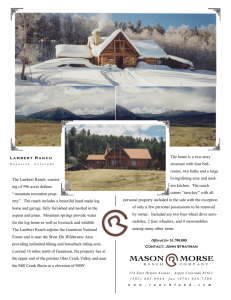

advertisement