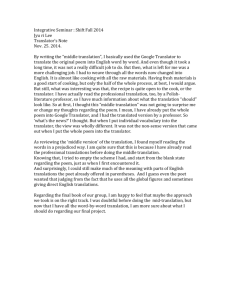

The Translation of Verga's Idiomatic Language

advertisement