Inter-American Court of Human Rights Case No. 12.367

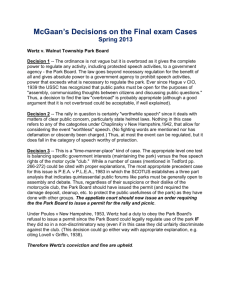

advertisement