Lesson 2: What Would You Decide? Hate Speech in the U.S.

advertisement

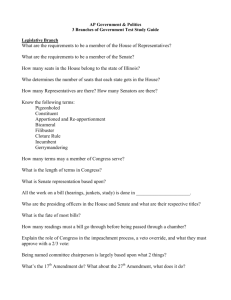

Lesson 2: What Would You Decide? Hate Speech in the United States Materials and Preparation: • Decide how you will structure the lesson. Option A is to organize the class into four groups and assign each group a different case. The groups can prepare for the moot court in their small groups; they can either simply do the moot court in their small group and then report out on their case to the class or all four groups can present their moot courts in front of the class. Option B would be to work through one or two of the cases as case studies and then organize the class into two groups; each group can prepare the arguments in one case, which they can then present to the other group, who will act as the Supreme Court justices in the case. Thus, each group will prepare one case and serve as the Court on the other. Option C, which is more time-­‐consuming would involve having the entire class work on all four moot courts, with students taking different roles for each case. An advantage of Options B and C is that, as the cases are presented, students doing later cases can draw on the earlier cases as precedents. • Make copies of handout #1, ”Precedents in U.S. Law” and handout #2, “Supreme Court Procedure” handouts for all students. • Make copies of the Prep Sheets and Case Materials (handouts #3 and #4); the number of copies you need of each set of Case Materials will depend on how you plan to structure the lesson. • You may wish to use the “Moot Court Rubric,” “Moot Court Reflection,” or “Moot Court Reporter Prep Sheet” provided as pdf files in the Resources section. Procedure: 1. Write on the board or project the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” Tell students that, as they learned in the last lesson, the United States has a very strong tradition of protecting freedom of speech. Yet freedom of speech does have limits. In this lesson, students will explore what those limits are, particularly when the case involves hate speech. 2. Explain that students will have the opportunity to take part in a moot court of one or more First Amendment/hate speech cases. A moot court is a simulation of a hearing in an appellate court; in the cases in this lesson, the moot courts will involve arguments before the U.S. Supreme Court. The cases have reached the Supreme Court by being appealed from the trial court to the Court of Appeals. Now they are being appealed again to the Supreme Court. 3. If students have not previously studied the work of appellate courts, you may want to spend some time on two concepts: Center for Education in Law and Democracy 1 Judicial review: The courts’ power to look at laws passed by government or actions taken by government—including governments at the local, state, and national levels—and decide whether they violate the U.S. Constitution. If the courts determine that the law or action does violate the Constitution, they can strike down the law or forbid the action as unconstitutional. • Precedents: Earlier cases about similar issues that establish a rule or principle by which later cases can be decided. Precedents are a very important part of the reasoning process by which appellate courts decide cases. Pass out the “Precedents in U.S. Law” handout and go over the cases with students. 4. Distribute the “Supreme Court Procedures” handout and go over the procedure with students, explaining that they will need to know these procedures as they prepare for and take part in a moot court. Project the two prep sheets (one for attorneys and one for Supreme Court justices) and explain that students will be using these handouts to prepare for their roles in the moot court. 5. Conduct the moot courts using the option you chose while preparing for the lesson. Briefly, those options are: Option A: Organize the class into four groups, assigning one case to each group. Each small group should be divided into three teams: (a) attorneys for the petitioner, (b) attorneys for the respondents, and (c) Supreme Court (this team should have an odd number of members). Give each group the relevant Case Materials and make sure they have access to the Prep Sheets. Allow time for students to prepare for the moot courts. Conduct the moot courts. Depending on the time available, you may have all four courts going on simultaneously. Following the moot courts, each group should provide a brief report on their case and the Court’s finding. If more time is available, you may conduct the moot courts one at a time, allowing students to observe the other moot courts. After each case is presented, share the actual Supreme Court decision in the case (see box at end of lesson). Option B: Work through the first two cases—R.A.V. v. St. Paul and Wisconsin v. Mitchell—as case studies, reviewing the facts of the case and the constitutional question and then asking students how they think the Court decided the cases. Share the results of the two cases. Next, organize the class into two groups. Assign each group one of the remaining two cases. Divide each group into attorneys for the petitioner and attorneys for the respondent. Give each group the relevant Case Materials and make sure they have access to the Prep Sheets. Allow time for students to prepare their arguments. When they are almost ready, ask each group to designate an odd number of group members to serve as the Supreme • Center for Education in Law and Democracy 2 Court for the other case. Take these students aside and give them the Case Materials for the other case so they can get a handle on the facts of the case before starting their service on the Court. Conduct the two moot courts, one after the other. After each case is presented, share the actual Supreme Court decision in the case (see box at end of lesson). Option C: Introduce the first case to the class; divide the class into four groups— attorneys for the respondent, attorneys for the petitioner, Supreme Court justices, and reporters (a Prep Sheet for reporters is provided in the Resource Section at the end of the unit). Distribute the Case Materials for the first case and make sure students have access to the Prep Sheets. Allow time for students to prepare for the moot court. Conduct the moot court and then share the actual Supreme Court decision in the case (see box at end of lesson). Continue through the rest of the cases, rotating students’ assignment with each case. Supreme Court Decisions R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992) The Court ruled the St. Paul ordinance invalid under the First Amendment. In a 9-­‐to-­‐0 vote, the justices held the ordinance invalid on its face because “…it prohibits otherwise permitted speech solely on the basis of the subjects the speech addresses...” The First Amendment prevents government from punishing speech and expressive conduct because it disapproves of the ideas expressed. Under the ordinance, for example, one could hold up a sign declaring all anti-­‐semites are bastards but not that all Jews are bastards. Government has no authority “to license one side of a debate to fight freestyle, while requiring the other to follow the Marquis of Queensbury Rules.” Furthermore, the Court concluded, “…Let there be no mistake about our belief that burning a cross in someone’s front yard is reprehensible. But St. Paul has sufficient means at its disposal to prevent such behavior without adding the First Amendment to the fire.” Wisconsin v. Mitchell (1993) Mitchell's First Amendment rights were not violated by the application of the penalty-­‐ enhancement provision in sentencing him because the statute has no “chilling effect” on free speech. Mitchell's conviction and increased penalty were held to be constitutional. The freedom to have racist thoughts does not give Americans the right to commit crimes for racist reasons. The Court also determined that the consequences for the victim and the community tended to be more severe when the victim of a crime was chosen on account of race. Thus, when the Wisconsin statute increased the sentence for such crimes, it was not punishing the defendant for his or her bigoted beliefs or statements, but rather the “predicted ramifications of his or her crime.” Center for Education in Law and Democracy 3 Virginia v. Black (2003) This case tested the ability of government to regulate a form of symbolic expression associated with racial hatred and violence. Burning a cross in the United States is linked to the Ku Klux Klan, a group that has historically demonstrated extreme racial hatred. The Court held that Virginia’s statute against cross burning was unconstitutional, even though “….cross burning to intimidate can be limited because such expression has a long and insidious history as a signal of impending violence…” A bedrock principle of the First Amendment is that government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea repugnant or offensive. The statute is unconstitutional because it permits Virginia to arrest a person based solely on the fact of cross burning itself. Therefore, the Court reasoned, to punish this act would create a suppression of ideas. Snyder v. Phelps (2011) The U.S. Supreme Court, by an 8-­‐1 vote, affirmed the lower court’s decision. The Court held that the First Amendment shields those who stage a protest at the funeral of a military service member from liability. Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the Court, said, “Given that Westboro's speech was at a public place on a matter of public concern, that speech is entitled to ‘special protection’ under the First Amendment” and “cannot be restricted simply because it is upsetting or arouses contempt.” Judge Samuel Alito cast the only dissenting vote. In his opinion, Alito wrote, “Our profound national commitment to free and open debate is not a license for the vicious verbal assault that occurred in this case. . . In this case, respondents brutally attacked Matthew Snyder, and this attack, which was almost certain to inflict injury, was central to respondents’ well-practiced strategy for attracting public attention.” Center for Education in Law and Democracy 4 Lesson 2 Handout 1 Precedents in U.S. Law Precedents are earlier cases about similar issues that establish a rule or principle by which later cases can be decided. Precedents are a very important part of the reasoning process by which appellate courts decide cases. The following are a few precedent cases on hate speech and the First Amendment: Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire (1942) Walter Chaplinsky was a member of Jehovah’s Witnesses. He often passed out religious pamphlets and spoke on the streets of Rochester, New Hampshire. One Saturday, people listening to his speech got upset when he called other religions “a racket.” The town marshal told the crowd that Chaplinsky’s actions were legal. After the marshal left, a fight broke out. Police took Chaplinsky to the police station for his own protection. There, he cursed at the marshal and called him a “Fascist.” He was arrested and charged with breach of the peace under a state law that says “No person shall address any offensive, derisive or annoying word to any other person who is lawfully in any street or public place, nor call him by any offensive or derisive name, nor make any noise or exclamation in his presence and hearing with intent to deride, offend or annoy him.” Chaplinsky was convicted and then appealed, claiming that the statute violated his rights to free speech and free press, as well as his freedom of religion. The New Hampshire Supreme Court described Chaplinsky’s language as “fighting words”—words that are “equally likely to cause violence.” It upheld his conviction. Chaplinsky appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which voted 9-­‐0 to uphold his conviction. Writing for the Court, Justice Frank Murphy said, “There are certain well-­‐defined and narrowly limited clases of speech, the prevention and punishment of which have never been thought to raise any Constitutional problem. These include the lewd and obscene, the profane, the libelous, and the insulting or ‘fighting’ words—those which by their utterance inflict injury or tend to incite an immediate breach of the peace.” Terminiello v. Chicago (1949) Fr. Arthur Terminiello was a Catholic priest who hated Jewish people. He gave a speech in Chicago that caused protestors to riot. The city of Chicago arrested him under a law that banned riotous speech, and he was convicted. In a 5-­‐4 vote, the Supreme Court overturned his conviction. Justice William O. Douglas wrote in the Court’s decision that speech is "protected against censorship or punishment, unless shown likely to produce a clear and present danger of a serious substantive evil that rises far above public inconvenience, annoyance, or unrest . . . There is no room under our Constitution for a more restrictive view." Center for Education in Law and Democracy 5 Beauharnais v. Illinois (1952) Joseph Beauharnais was president of the White Circle League, a racist organization. In January 1950, he was passing out leaflets on the street corner in Chicago. The leaflets asked the mayor and city council to “to halt the further encroachment, harassment and invasion of white people…by the Negro.” Beauharnais was arrested and charged with violating an Illinois law making it illegal to distribute any publication that "exposes the citizens of any race, color, creed or religion to contempt, derision, or obloquy." A jury found him guilty, and he was fined $200. The Illinois Supreme Court upheld his conviction. Beauharnais appealed, claiming the Illinois law violated his rights under the First and Fourteenth Amendments. The Supreme Court found, in a 5-­‐4 vote, in favor of the state of Illinois. Justice Felix Frankfurter, writing for the Court, said that Beuharnais' speech amounted to libel and was therefore beyond constitutional protection. The Court took into account the racial tensions of the day, saying that Beuharnais' speech was provocative give the circumstances. It rejected the argument that the Illinois statute could be easily abused, stating, “Every power may be abused, but the possibility of abuse is a poor reason for denying Illinois the power to adopt measures against criminal libels sanctioned by centuries of Anglo-­‐American law.” Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) Clarence Brandenburg, a leader of a Ku Klux Klan (KKK) group in Hamilton County, Ohio, organized a rally and asked a TV news reporter to cover the event. The rally included Klan members dressed in KKK uniforms and carrying firearms. They burned a cross; some spoke hateful comments about African Americans and Jews. In his speech, Brandenburg said “…the KKK might have to seek revenge if the President, Congress, and the Supreme Court continues to suppress white Americans...” Ohio charged Brandenburg with violating a state law that made it a crime to assemble a group of people to teach or support sabotage, violence, or other unlawful ways to change the government. He was convicted, fined $1,000, and sentenced to one to ten years' imprisonment. Brandenburg challenged the constitutionality of the statute under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. (The Fourteenth Amendment has been said to incorporate the states under the First Amendment, which is why it is mentioned in this and other cases.) The U.S. Supreme Court held that government cannot punish inflammatory speech unless it is directed to inciting and likely to incite imminent lawless action. The Court unanimously reversed Brandenburg’s conviction because there was no proof that he was inciting imminent lawless action or that such action was likely to occur. The Supreme Court overruled Ohio's statute, because it broadly prohibited the mere advocacy of violence. Center for Education in Law and Democracy 6 National Socialist Party v. Village of Skokie (1977) The American Nazi Party planned a demonstration in the village of Skokie, Illinois. Most of Skokie’s residents were Jewish and many were survivors of Nazi concentration camps during World War II. Many others had lost relatives in Hitler’s gas chambers. Not surprisingly, many residents strongly opposed a Nazi demonstration in their town. To prevent violence and property damage, the town passed a law that it hoped would keep the Nazis from demonstrating. The law required groups to obtain $300,000 in liability insurance in order to get a permit to legally demonstrate. However, the town could waive this requirement. The same law also banned distribution of materials promoting racial or religious hatred and prohibited public demonstration by people in military-­‐style informs. The Nazis challenged the law as a violation of their First Amendment rights. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit held that the village ordinances designed to stop the Nazis from demonstrating in Skokie were unconstitutional. (The Nazi group then canceled its plan.) Center for Education in Law and Democracy 7 Lesson 2 Handout #2 Supreme Court Procedure Most federal cases that make it to the Supreme Court start in one of the 94 federal district courts in the United States. If the defendant loses the case, he/she can appeal in one of the 13 courts of appeals across the country. Whoever loses the case in the appeals court can file a writ of certiorari, which asks the Supreme Court to hear the case. Other cases come to the Supreme Court through appeal from state courts. A few cases originate in the Supreme Court due to constitutional provisions. If the Supreme Court grants cert (agrees to hear a case), the lawyers present written briefs detailing their arguments. The Court also holds a hearing, in which the attorneys for each party make their arguments and the Justices ask questions. The name of the case gives the petitioner first—that is the person who lost in the lower court and has petitioned the Supreme Court to hear the case. The respondent—the person who won in the lower court and is responding to the petitioner—is the second name in the case. So, for example, in the case of Miller v. Colorado, Miller lost in the lower court and is the petitioner. Colorado won in the lower court and is the respondent. In the hearing, the petitioner goes first, the respondent second. There is a strict time limit, and the justices can interrupt at any time to ask questions. Sometimes, the attorneys barely have time to present a few sentences from their prepared remarks before they are interrupted. After hearing the case, the Court does not usually announce its decision for a few months. The justices meet in private sessions to discuss the cases. They try to change their colleagues’ minds through these discussions and memos that circulate among the justices. When the final vote is taken, the majority rules; that is, at least five of the nine Justices must vote together to reach a verdict. One Justice writes the Court’s opinion, called the majority opinion. Other Justices can write concurring opinion, which agrees with some parts of the Court’s opinion and disagrees with others. Any Justice may also write a dissenting opinion, which disagrees with the Court’s decision. In our moot court, the procedure will not be completely accurate: 1. Petitioner’s argument and questions from Justices (3-­‐5 minutes) 2. Respondent’s argument and questions from Justices (3-­‐5 minutes) 3. Rebuttal—petitioner (2 minutes) 4. Rebuttal—respondent (2 minutes) 5. Deliberation and vote—Justices (10 minutes) Center for Education in Law and Democracy 8 Lesson 2 Handout #3 Moot Court Attorney Prep Sheet Name of Case: Party Represented: Essential Facts of the Case: Issue: Arguments: For each argument you plan to make, try to identify a precedent case. Also, focus on why this argument is compelling to the national interest. Argument 1: a. Precedent and why it applies: b. Why this argument is compelling (how it affects the national interest): Center for Education in Law and Democracy 9 Argument 2: a. Precedent and why it applies: b. Why this argument is compelling (how it affects the national interest): Argument 3: a. Precedent and why it applies: b. Why this argument is compelling (how it affects the national interest): What arguments will the opposing side make? How might you counter those arguments? Center for Education in Law and Democracy 10 Lesson 2 Handout #3 Moot Court Supreme Court Justice Prep Sheet Name of Case: Essential Facts of the Case: Issue: Significance of Issue to the National Interest: Relevant Precedents: Questions for Petitioner: Questions for Respondent: Center for Education in Law and Democracy 11 Lesson 2 Handout #4 Case Materials: R.A.V. v. St. Paul R.A.V v. St. Paul (1991) Facts of the Case: In the 1980s, many states and cities enacted laws aimed at curtailing hate speech, which was seen as a widespread problem. The city of St. Paul, Minnesota, had enacted such an ordinance, which was known as the St. Paul Bias-­‐Motivated Crime Ordinance. That ordinance is at the heart of the case of R.A.V. v. St. Paul. In the “predawn hours” of June 21, 1990, several white teenagers in St. Paul, Minnesota, made a crude cross by taping together the broken legs of several chairs. They set up the cross inside the fenced front yard of an African-­‐American family who lived across the street from R.A.V.’s home. (The petitioner’s name is not given because he was a juvenile at the time.) The teenagers set the cross on fire, in obvious reference to cross burnings by the Ku Klux Klan. R.A.V. was arrested and charged with two counts, including a violation of the St. Paul Bias-­‐ Motivated Crime Ordinance. This “…prohibits the display of a symbol which one knows or has reason to know arouses anger, alarm or resentment in others on the basis of race, color, creed, religion or gender…” The trial court dismissed this charge on the basis that the ordinance was substantially overbroad, content-­‐based, and therefore unconstitutional under the First Amendment. The Minnesota Supreme Court reversed this decision, stating that the ordinance was an appropriate means of accomplishing a compelling government interest in protecting the community from bias-­‐motivated threats to public safety and order. It held, as it had in previous cases, that the St. Paul ordinance was in line with the fighting words doctrine under Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire. The case was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Question: Does the St. Paul Bias-­‐Motivated Crime Ordinance violate the First Amendment? Arguments: • The St. Paul ordinance punishes speech with specific content. This makes it unconstitutional under the First Amendment. • The ordinance specifically prohibits speech that will arouse “anger, alarm or resentment.” Such speech can be considered “fighting words,” unprotected by the First Amendment according to the case of Chaplinsky v. New Hampshire. • The ordinance addresses a compelling government interest: protecting the community against bias-­‐motivated violence that threatens public safety. Center for Education in Law and Democracy 12 • The ordinance does not address all “fighting words.” Instead, it places a particular burden on people who express racial, religious, or gender bias. Thus, it discriminates against a particular viewpoint and is unconstitutional. Center for Education in Law and Democracy 13 Lesson 2 Handout #4 Case Materials: Wisconsin v. Mitchell Wisconsin v. Mitchell (1993) Facts of the Case: In the 1980s, many states and cities enacted laws aimed at curtailing hate speech, which was seen as a widespread problem. One approach to the problem was to enhance penalties for criminal convictions, if the crime was motivated by bias. That was the kind of law at issue in the case of Wisconsin v. Mitchell. In October 1989, Todd Mitchell, a young black man, was discussing the movie Mississippi Burning with a group of friends at an apartment complex in Kenosha, Wisconsin. They were discussing a scene in which a white man beat up a young African America. In talking about the scene, the young people got very upset and angry. Mitchell reportedly asked others in the group, “Do you all feel hyped up to move on some white people?” He spotted Gregory Reddick, a 14-­‐year-­‐old white boy across the street. Reddick was walking home from a pizza place. Mitchell then said “You all wan to f*&^ somebody up? There goes a white boy; go get him.” Several people chased Reddick. One kicked him, knocking him to the ground, where they surrounded him. They kicked, hit, and stomped on Reddick for about five minutes, leaving him unconscious. When the police found Reddick some time later, he was still unconscious. Although he was in a coma for four days, he fully recovered from the attack Mitchell was arrested, charged, and convicted of aggravated battery. According to Wisconsin law, Mitchell's sentence was increased because the court found that he had intentionally selected his victim based on race. Mitchell challenged the constitutionality of the increase in his penalty, but the Wisconsin Court of Appeals rejected his claims. However, the Wisconsin Supreme Court reversed. The state appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Question: Does the Wisconsin law enhancing penalties for bias-­‐motivated crimes violate the First Amendment’s free speech clause? Arguments: • The Wisconsin law is unconstitutional because it punishes people for thoughts that are offensive to the legislature. This is clearly in violation of the First Amendment because it discriminates on the basis of the content of speech. • The Wisconsin law only punishes the behavior—the process by which the criminal selected the victim of the crime. Center for Education in Law and Democracy 14 • The law is unconstitutionally overbroad because it requires the prosecution to provide evidence of a person’s prior speech. This would create a “chilling effect” on free speech, causing people to self-­‐censor out of fear. • The Wisconsin law serves the same purpose as anti-­‐discrimination law: to prevent behavior that targets members of certain groups. In this case, it targets violent behavior and thus serves a compelling state interest. Center for Education in Law and Democracy 15 Lesson 2 Handout #4 Case Materials: Virginia v. Black Virginia v. Black (2003) Facts of the Case: In 1952, Virginia was experiencing increasing racial tension. In response, the state enacted a law making it a crime to burn a cross on someone else’s property—a favorite tactic of the white supremacist organization, the Ku Klux Klan. Sixteen years later, the state extended the ban to cross burning in all public places. The law provided that burning the cross was “prima facie evidence of an intent to intimidate a person or group.” On August 22, 1998, Barry Elton Black, a member of the Ku Klux Klan, led a rally and cross burning in Carroll County, Virginia, According to Black, the purpose was to recruit new members. The event took place on private property, with the owner’s permission, and in public view. The 25-­‐foot-­‐tall cross burned at the rally was visible from the nearby state highway. Black, who admitted responsibility for the cross burning, was charged with violating the Virginia law that makes it a felony for any person “ . . . with the intent of intimidating any person or group . . . to burn . . . a cross on the property of another, a highway or other public place.” At Black’s trial, both white and black people testified that they were intimidated and scared by the cross burning. Black was found guilty. He appealed the conviction, which was overturned by the Virginia Supreme Court. The court struck down the cross-­‐burning law because it prohibits a form of expression solely on the basis of its content. The Virginia Supreme Court said that the law not only discriminates on the basis of content and viewpoint but it also selectively bans only cross burning because of its distinctive message. The Commonwealth of Virginia then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. Question: Does the Commonwealth of Virginia's cross-­‐burning statute, which prohibits the burning of a cross with the intent of intimidating any person or group of persons, violate the First Amendment? Arguments: • The law is not directed toward speech that has a particular content focus. It is directed at speech that is designed to intimidate. Traditionally—particularly in Southern states—cross burning has legitimately been seen as a threat. • Some cross burning does represent a threat. But a cross may be burned for another purpose. In this case, Black claimed he was trying to recruit new members to the KKK, not to intimidate anyone. Center for Education in Law and Democracy 16 • • The state has a compelling interesting in improving race relations in the state. Because of the intimidating message that cross-­‐burning was historically used to convey, the state should be able to suppress this type of speech. The law defines cross burning as intimidation. Thus, a person arrested for burning a cross is essentially assumed to be guilty, which flies in the face of the underpinnings of the U.S. justice system. Center for Education in Law and Democracy 17 Lesson 2 Handout #4 Case Materials: Snyder v. Phelps Snyder v. Phelps (2011) Facts of the Case: The Westboro Baptist Church is a small church in Topeka, Kansas. Most of its members are related to the church’s pastor, Fred Phelps. The church opposes homosexuality. To draw attention to its views, members of the church often picket the funerals of members of the military. (They target service men and women whether they are gay or not.) They carry signs that say things like “America is doomed,” “Thank God for dead soldiers,” “God hates you,” “Fag troops,” and “Thank God for IEDs [the roadside bombs that killed and injured many service men and women in Iraq].” On March 3, 2006, U.S. Marine Lance Corporal Matthew A. Snyder, was killed in a car accident in Iraq. At his funeral on March 10, members of the Westboro Baptist Church picketed. Members of the Patriot Guard Riders were at the funeral. This group tries to block the bereaved family from seeing the protesters. Albert Snyder, Matthew’s father, sued Fred Phelps, the church, and two of Phelps’ daughters for intrusion upon seclusion, intentional infliction of emotional distress, and civil conspiracy. At the trial, Snyder testified that the funeral became a “media circus” rather than the dignified event his son deserved. He also described being made emotionally upset and physically ill because of the church’s activities. Experts testified that the defendant’s actions made Snyder’s diabetes worse and sent him into a depression. Phelps and his co-­‐ defendants argued that Snyder could not even see the content of the protest signs because of the shield provided by the Patriot Guard. The jury found in favor of Snyder, and the family was awarded $5 million in damages. On appeal, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit held that the judgment violated the First Amendment's protections of religious expression. The church members’ speech is protected, "notwithstanding the distasteful and repugnant nature of the words.” Snyder was ordered to pay the defendants’ court costs. He appealed the case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Question: Can a private individual or organization be held liable for the intentional infliction of emotional distress through hateful speech when their language is commenting on matters of public concern? Arguments: • The First Amendment does not give people the right to express opinions in a way that harms others. This is especially true when the people harmed are private individuals, Center for Education in Law and Democracy 18 • • • not public figures. In addition, in this case they were private individuals at a particularly vulnerable time—the funeral of a family member. Westboro Baptist Church is commenting on public issues, such as the role of homosexuals in the military. Speech on public/government matters has the highest level of protection by the First Amendment. The Westboro Baptist Church may have the right to express its views, but by targeting grieving families, they are doing so at an inappropriate time and place. Furthermore, some of their signs specifically target the family (“God hates you”), which is not a public issue. The church members were on public property. They followed all the laws about where and when the protest could occur. Suggesting that their expression was inappropriate is an attack on the content of what they said. Further, they did not personally attack the Snyder family. They were expressing views on issues of public concern. Center for Education in Law and Democracy 19