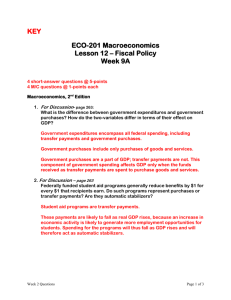

Murphy, Steven B. :Financial management in a

advertisement