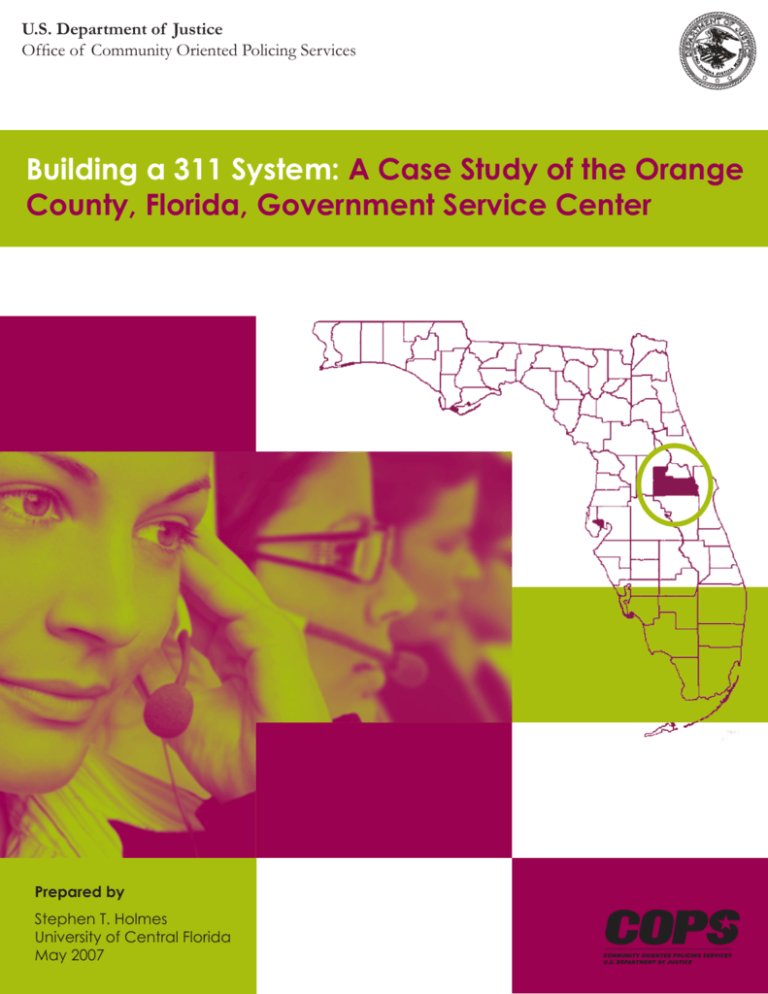

Building a 311 System: A Case Study of the Orange County, Florida

advertisement