A Final Assessment of Stages Theory

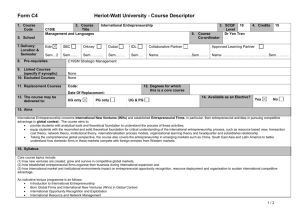

advertisement