Use of Iodized Salt in Processed Foods in Select Countries Around

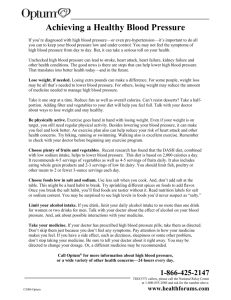

advertisement