Direct-to-store distribution Impact on European Ports Final Report

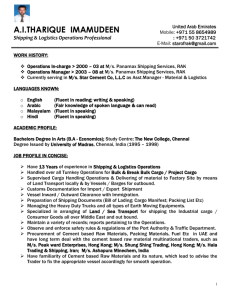

advertisement