The Human Appendix Wisdom Teeth in Humans The Blind Fish

advertisement

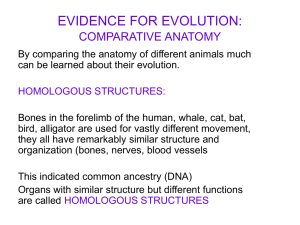

Top 10 Useless Limbs (and Other Vestigial Organs) Source: http://www.livescience.com/11317-­‐top-­‐10-­‐useless-­‐limbs-­‐vestigial-­‐organs.html The Human Appendix In plant-eating vertebrates, the appendix is much larger and its main function is to help digest a largely herbivorous diet. The human appendix is a small pouch attached to the large intestine where it joins the small intestine and does not directly assist digestion. Biologists believe it is a vestigial organ left behind from a plant-eating ancestor. Interestingly, it has been noted by paleontologist Alfred Sherwood Romer in his text The Vertebrate Body (1949) that the major importance of the appendix "would appear to be financial support of the surgical profession", referring to, of course, the large number of appendectomies performed annually. In 2000, in fact, there were nearly 300,000 appendectomies performed in the United States, and 371 deaths from appendicitis. Any secondary function that the appendix might perform certainly is not missed in those who had it removed before it might have ruptured. Wisdom Teeth in Humans With all of the pain, time, and money that are put into dealing with wisdom teeth, humans have become just a little more than tired of these remnants from their large jawed ancestors. But regardless of how much they are despised, the wisdom teeth remain, and force their way into mouths regardless of the pain inflicted. There are two possible reasons why the wisdom teeth have become vestigial. The first is that the human jaw has become smaller than its ancestors -and the wisdom teeth are trying to grow into a jaw that is much too small. The second reason may have to do with dental hygiene. A few thousand years ago, it might be common for an 18 year old man to have lost several, probably most, of his teeth, and the incoming wisdom teeth would prove useful. Now that humans brush their teeth twice a day, it's possible to keep one's teeth for a lifetime. The drawback is that the wisdom teeth still want to come in, and when they do, they usually need to be extracted to prevent any serious pain. The Blind Fish Astyanax Mexicanus In an experiment designed by nature, the species of fish known as Astyanax mexicanus, dwelling in caves deep underground off the coast of Mexico, cannot see. The pale fish has eyes, but as it is developing in the egg, the eyes begin to degenerate, and the fish is born with a collapsed remnant of an eye covered by flap of skin. These vestigial eyes probably formed after hundreds or even thousands of years of living in total darkness. As for the experiment, a control is needed; and luckily for us, fish of the same species live right above, near the surface, where there is plenty of light, and these fish have fully functioning eyes. To test if the eyes of the blind mexicanus could function if given the right environment, scientists removed the lens from the eye of the surfacedwelling fish and implanted it into the eye of the blind fish. It was observed that within eight days an eye started to develop beneath the skin, and after two months the fish had developed a large functioning eye with a pupil, cornea, and iris. The fish were blind, but now they see. The Human Tailbone (Coccyx) These fused vertebrae are the only vestiges that are left of the tail that other mammals still use for balance, communication, and in some primates, as a prehensile limb. As our ancestors were learning to walk upright, their tail became useless, and it slowly disappeared. It has been suggested that the coccyx helps to anchor minor muscles and may support pelvic organs. However, there have been many well documented medical cases where the tailbone has been surgically removed with little or no adverse effects. There have been documented cases of infants born with tails, an extended version of the tailbone that is composed of extra vertebrae. There are no adverse health effects of such a tail, unless perhaps the child was born in the Dark Ages. In that case, the child and the mother, now considered witches, would've been killed instantly. Erector Pili and Body Hair The erector pili are smooth muscle fibers that give humans "goose bumps". If the erector pili are activated, the hairs that come out of the nearby follicles stand up and give an animal a larger appearance that might scare off potential enemies and a coat that is thicker and warmer. Humans, though, don't have thick furs like their ancestors did, and our strategy for several thousand years has been to take the fur off other warm looking animals to stay warm. It's ironic actually that an animal, sensing danger is near, would puff up its coat to look scarier, but the human hunter would see the puffier coat as a warm prize, leaving the thinner haired weaker looking animals alone. Of course, some body hair is helpful to humans; eye brows can keep sweat out of the eyes and facial hair might influence a woman's choice of sexual partner. All the rest of that hair, though, is essentially useless. Hind Leg Bones in Whales Biologists believe that for 100 million years the only vertebrates on Earth were waterdwelling creatures, with no arms or legs. At some point these "fish" began to develop hips and legs and eventually were able to walk out of the water, giving the earth its first land lovers. Once the land-dwelling creatures evolved, there were some mammals that moved back into the water. Biologists estimate that this happened about 50 million years ago, and that this mammal was the ancestor of the modern whale. Despite the apparent uselessness, evolution left traces of hind legs behind, and these vestigial limbs can still be seen in the modern whale. There are many cases where whales have been found with rudimentary hind limbs in the wild, and have been found in baleen whales, humpback whales, and in many specimens of sperm whales. Most of these examples are of whales that had only leg bones, but there were some that included feet with complete digits. It was reported recently that whales and hippos were distantly related. The Wings on Flightless Birds In 1798, sixty years before Charles Darwin's first book was published, a French anatomist, É´ienne Geoffroy St. Hilaire, traveled to Egypt with Napoleon where he witnessed and wrote about a flightless bird whose wings appeared useless for soaring. The bird that Hilaire described was an ostrich, but he described it as a "cassowary", a term used back then to describe various birds of ostrich-like appearance. Ostriches and cassowaries are among several birds that have wings that are vestigial. Besides the cassowary, other flightless birds with vestigial wings are the kiwi, and the kakapo (the only known flightless and nocturnal parrot), among others. In general, wings of a bird are considered complex structures that are specifically adapted for flight and those belonging to these flightless birds are no different. They are, anatomically, rudimentary wings, but they could never give these bulky birds flight. The wings are not completely useless, as they are used for balance during running and in flagging down the honeys during courtship displays.

![2.3_the_top_10_vestigial_structures[1].](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/010173220_1-31860a8aebbfa223def67eca3a90666c-300x300.png)