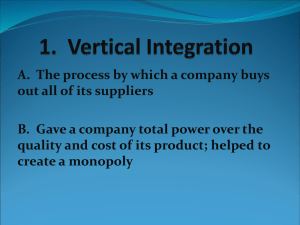

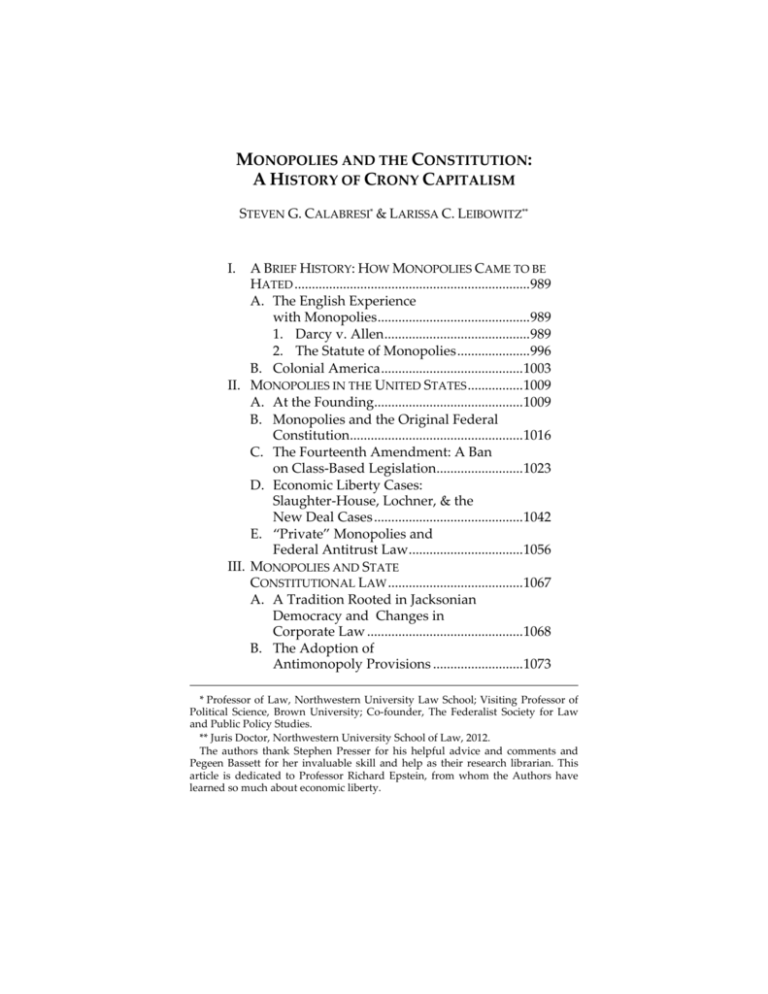

monopolies and the constitution

advertisement