Lyndsay Amiro Amiro 1 Dr. Lipscomb ENG 4934 26 April 2012 The

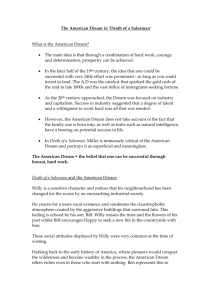

advertisement

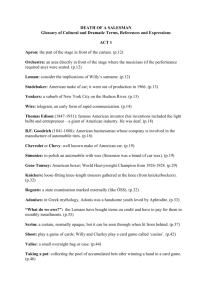

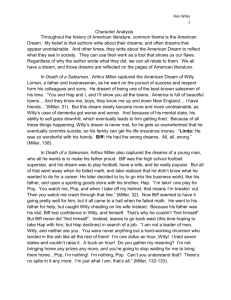

Lyndsay Amiro Amiro 1 Dr. Lipscomb ENG 4934 26 April 2012 The Wrong Dream in Death of a Salesman Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman remains a timeless masterpiece because of its ongoing impact on society. It was a hit right away and has remained one of the most popular plays of all time. Miller focuses Death of a Salesman on “the American ideal of business success” and “its conclusions were challenged to standard American business values” (Loeffelholz 700). Death of a Salesman can be seen in a variety of different ways, from tragedy to memory, which contribute to its ongoing study. Around the world, but specifically in America, Willy Loman remains a business icon who is a reflection of us. Willy has the wrong dream all along and this is what ultimately leads to his downfall. He puts too much emphasis on being “well-liked” as successful, rather than hard work and dedication. The cultural context of Death of a Salesman plays a major role because of society’s expectations dealing with the American Dream. These expectations cause Willy’s fatal error in judgment, the wrong dream, which is the origin of his inevitable failure. In this context, this is a play about the American family and the American Dream. WWII and The Great Depression had a worldwide impact and affected numerous families. “The suicides of millionaire bankers and stockbrokers made the headlines, but more compelling was the enormous toll among ordinary people who lost homes, jobs, farms, and life savings in the stock market crash” (Norton Anthology 1185). Although Willy would have started Amiro 2 his career a great many years prior to this, the 1940’s, in which the play is set, is a time when the job market was more demanding thus causing him to fail as a salesman due to his lack of skills. As a result of this, Willy does not live up to his version of the American Dream of being a successful salesman. “Willy Loman entered the world’s consciousness as the very image of the traveling salesman,” states Murphy, but in the end he does not live up to this image. In the 1940’s it was common for Americans to feel disillusioned about the American Dream. According to James Ryan and Leonard Schulp, authors of the Historical Dictionary of the 1940’s , the nation was still coping from The Great Depression and some minority groups were seeing the American Dream as a nightmare. “As the war dragged on, these groups became more vocal in their pursuit of the American Dream, thereby raising expectations to a higher level.” In the 19th century version of the American Dream a single man went out into nature and tried to make a fortune from the land. In the 20th century this idea shifted to focus more on an industry full of service and sales as representation of the American Dream. For example, Willy’s brother Ben says, “Why, boys, when I was seventeen I walked into the jungle, and when I was twenty-one I walked out. (He laughs.) And by God I was rich” (Miller 1.715). Ben represents what Willy hoped to achieve in life; his idealized American Dream. Willy regrets settling for a lesser dream of being a salesman and wonders why he didn’t go to Alaska with Ben when he had the chance. Ben provides Willy with nothing but dreams and empty promises that push him further into delusion. For while Ben is undoubtedly the embodiment of one kind of American dream to Willy, so too is Dave Singleman representative of another kind--and that is part of Willy's Amiro 3 confusion: both men symbolize the American dream, yet in his mind they represent value systems that are diametrically opposed to each other. The memory scenes are important in bringing out this contrast and showing what Willy's perception of Ben reflects about Willy's own conflicting values (Centola). Because Willy did not accept Ben’s offer, we can see this as “his need to preserve the dream, and not jeopardize it by too close a contact with reality. His rejection of Charley’s job offer, on the other hand, is a result of a refusal to admit that he has failed” (Benziman). Instead of moving forward with his life and accepting a job from someone like Charley further emphasize his error. Society’s expectations were demanding and Willy was not able to live up to them because of his attachment with the past. Looking at the cultural context and the time period of the play, it is evident that Willy was delusional and too caught up in what really had no significance. Society was interested in a man who could make a name for himself and his family through hard work and dedication, not being well-liked. These changing times were in effect but Willy remained too focused on the past. Perhaps part of Willy’s failure as a salesman was that he was not going about it the right way. Perhaps he was not keeping up with the times and this is part of his failure. According to Murphy, the oldstyle career salesman is dead and maybe this signifies the end for Willy all along. To be like Willy is to be a failure. Therefore we will make the job of sales as different as we can from the job as Willy did it. Of course, this is a cultural, not a literary evocation. The point is that he represents the conjunction of traditional sales methods and failure. To Amiro 4 escape Willy's fate, the salesperson need simply follow this good advice.... if only Willy Loman had known what we do now (Murphy). As much as we relate Willy Loman to “failure” and “fear,” Americans need, and could not live without the salesman icon Willy Loman. He represents everything not to do, providing future salesman with a commentary on a rather failed life. In 1963, critic and director Esther Merle Jackson said that Death of a Salesman is “‘the most nearly mature myth about human suffering in an industrial age’” (Murphy). She states that Arthur Miller, “‘has formulated a statement about the nature of human crises in the twentieth century which seems, increasingly, to be applicable to the entire fabric of civilized experience.’” According to Jackson this play has more of an impact than others of its time because of the relationship between Willy Loman and contemporary life. Willy is quite literally symbolic for society at the time the play was written. He exemplifies the morals and values of the so-called American Dream at that time and how completely upside down they truly were. Willy believes that the promise of the American Dream is that if you are a well-liked man in business then you will acquire the material wealth offered by modern American life. He is fixated on all the wrong things in life: being liked instead of being hard-working as the key to success in order to obtain the American Dream. An example of this is Willy’s reactions to Bernard. He doesn’t like Bernard because he thinks he is a bore, but in reality Bernard is closer to reaching the American Dream because he is hard-working. WILLY: That’s just what I mean. Bernard can get the best marks in school, y’understand, but when he gets out in the business world, y’understand, you are Amiro 5 going to be five times ahead of him … Because the man who makes an appearance in the business world, the man who creates personal interest, is the man who gets ahead. Be liked and you will never want (Miller 1.711). Willy has a diluted vision of the American Dream which sets him up for a swift decline. Willy has instilled the idea in both Biff and Happy that being well-liked is the ultimate key to success. He tells them that they will not have to work hard for anything, and that everything will come very easy to them because of their likeability. Happy does not seem to question his father’s ideas, but Biff does. Happy does whatever it takes to gain approval from his father. He is constantly saying, “I’m losing weight, you notice, Pop?” in order to retrieve his father’s attention and be well-liked. Happy believes that being well-liked is truly the only way to be successful. Biff, however, is a little more skeptical on the matter. He wants to gain approval from his father while still remaining true to himself. He sits on both ends of the spectrum of the American Dream: outdoors and financial. According to Centola, both Biff and Happy are ‘lost’ and ‘confused,’ but this realization is not fully reached until the end of the play. Biff is worse off than Happy because he is able to recognize the problem where as Happy remains completely oblivious. Although Biff realizes the false sense of success that Willy is engraining into them, he still feels obligated to make something of himself in the business world for the sake of his father. What makes Death of a Salesman so impactful is the fact that what happens to Willy could happen to anyone; Willy’s fatal flaw of having the wrong dream evokes pity and fear in the reader. “While Miller clearly uses Willy's collapse to attack the false values of a venal American society, the play ultimately captures the audience's attention not because of its Amiro 6 blistering attack on social injustice but because of its powerful portrayal of a timeless human dilemma” (Centola). It is evident that anyone can feel and understand the anguish that Willy Loman went through. The effects of The Great Depression not only crushed the American Dream for Americans, but for humans worldwide. Centola states that “one can appreciate the intensity of Willy's struggle only after isolating the things that Willy values and after understanding how the complex interrelationship of opposed loyalties and ideals in Willy's mind motivates every facet of his speech and behavior in the play.” Once Willy’s values are analyzed and understood, the conflict between him and Biff is implicit: he recognizes his role in Biff’s failure. “At the root of Biff's wrongdoing and feelings of guilt lie shame and feelings of inadequacy and inferiority. But, unlike his father, he faces, and learns from, his shame” (Ribkoff). We understand that Willy is seen through Biff, but Biff still has a chance to redeem himself unlike his father. Where Willy does not know himself, Biff does and thus he is able to empathize with his father. Biff’s sense of inadequacy derives from his father and this recognition is what sends him “running home.” Biff cannot escape his fathers and his society’s ideas and expectations for success and the American Dream. It takes the shattering moment when Biff finds out about “The Woman” for his views toward his father change. Up until then Willy has been a role model, one whom Biff respects and admires. Even though Willy’s decisions are usually far from agreeable, the reader cannot help liking him; he is even “well-liked.” While most readers and audience members would disagree with his course of action, it is plain to see and understand the anguish and struggles Willy is Amiro 7 dealing with over the course of the play in his persistent pursuit of the impossible American Dream. Willy “tries to assure himself that he has made the right choices and has not wasted his life while he also prevents himself from questioning his conduct and its effect on his relations with others” (Centola). Without knowing it Willy is crying out for help, and even while longing for material success he wants to regain love and respect from his family along with the selfesteem he has lost. Sadly, he goes about striving to obtain these goals in the wrong way “because he has deceived himself into thinking that the values of the family he cherishes are inextricably linked with the values of the business world in which he works” (Centola). He confuses the two and tries to link them together, resulting in nothing but misfortune and embarrassment for himself and everyone around him. “The cultural impact of Death of a Salesman far exceeds the theatrical and literary experience, however. Willy Loman and his failure and death have a status as defining cultural phenomena, both inside and outside America's borders, that began to be established in the first year of the play's life” (Murphy). People were claiming that this play related to them on a personal level, businesses were using Willy as an example of what not to do as a salesman, and preachers were incorporating Willy into their sermons explaining the emptiness of his dreams of material success. Willy has maintained the wrong dream all along; he dreamed of being wellliked instead of hard working. The problem is particularly evident in the way Willy approaches the profession of salesmanship. Instead of approaching his profession in the manner of one who understands the demands of the business world, Willy instead convinces himself that his Amiro 8 success or failure in business has significance only in that it affects others-particularly his family’s-perception of him (Centola). Society has caused Willy to believe that the only way to be successful is to be well-liked; he cares about perception rather than substance. The Lomans live on charm and being well-liked rather than working hard to be successful. Charley serves as a foil to Willy because he has reached the American Dream. In Act II Charley points out to Willy that everything he has put so much focus on is really worth nothing WILLY: Charley, I’m strapped. I’m strapped. I don’t know what to do. I was just fired. CHARLEY: Howard fired you? WILLY: That snotnose. Imagine that? I named him. I named him Howard. CHARLEY: Willy, when’re you gonna realize that them things don’t mean anything? You named him Howard, but you can’t sell that. The only thing you got in this world is what you can sell. And the funny thing is that you’re a salesman, and you don’t know that (Miller 2.728). According to Cardullo, What we are left with in this play, then, is neither a critique of the business world nor an adult vision of something different and better, but the story of a man (granting he was Amiro 9 sane) who failed, as salesman and father--or who failed to live up to his own unrealistic dreams of what salesmanship and fatherhood constitute--and who made things worse by refusing to the end to admit those failures, which he knew were true. Willy is trapped, he refuses to look reality in the face and see himself and everyone else for what they are. This is a sign of his instability and failure to recognize the fact that he has made a fatal error in judgment by having the wrong dream. Both Willy and Biff have been unable to understand and acknowledge who they truly are until the end of the play. BIFF: No! Nobody’s hanging himself, Willy! I ran down eleven flights with a pen in my hand today. And suddenly I stopped, you hear me? And in the middle of that office building, do you hear this? I stopped in the middle of that building and I saw – the sky. I saw the things that I love in this world. The work and the food and time to sit and smoke. And I looked at the pen and said to myself, what the hell am I grabbing this for? Why am I trying to become what I don’t want to be? What am I doing in an office, making a contemptuous begging fool or myself, when all I want is out there, waiting for me the minute I say I know who I am! Why can’t I say that, Willy? (Miller 2.739). It isn’t until this moment Biff is able to see himself as he truly is. Willy, on the other hand, doesn’t seem so lucky. According to Ribkoff, Willy cannot bear to have his dreams and his vision of himself, and Biff, revealed before him that way. Continuing from the previous dialogue Biff says, “I am not a leader of men, Willy, and neither are you. You were never Amiro 10 anything but a hard-working drummer who landed in the ash can like the rest of them!” (Miller 2.739). Biff realizes who he is not and tries to get his father to understand as well; however, Willy cannot empathize because he is incapable of facing his own guilt. When Biff says, “Will you let me go, for Christ’s sake? Will you take that phony dream and burn it before something happens?” he is “not simply asking for his own freedom from the shame produced by not living up to the dream of success and being ‘well liked’; he is asking for his father's freedom from shame and guilt as well states Rubkoff. Willy is driven by shame to commit suicide at the close of the play; this is his last attempt at preserving the image of being “well-liked” not only as a salesman but as a father, too. Near the end of the play, in the most climactic scene, Biff realizes that he needs to face reality and himself unlike his father. But literally a couple pages before this Willy is talking to Ben about what it will be like at his funeral. WILLY: Because he thinks I’m nothing, see, and so he spites me. But the funeral(Straightening up.) Ben, that funeral will be massive! They’ll come from Maine, Massachusetts, Vermont, New Hampshire! All the old-times with the strange license plates-that boy will be thunderstruck, Ben, because he never realized-I am known! Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey-I am known, Ben and he’ll see it with his eyes once and for all. He’ll see what I am, Ben! He’s in for a shock, that boy! BEN: (coming down to the edge of the garden): He’ll call you a coward (Miller 2.736). Amiro 11 Willy still doesn’t get it even this far into the play, and the fact is he never will. He is still set on being well-liked and focusing on how many people will attend his funeral. Willy has been making a fool of himself and even when both Ben and Biff point it out he is still unwilling to listen. According to Centola, Biff realizes that his dreams have nothing to do with Willy’s own vision of success. Biff is able to embrace and understand who he is and stop living a lie. In the Requiem Biff makes the announcement that “he had the wrong dreams. All, all wrong” (Miller 741). He also states that Willy didn’t know who he was but that he knows who he is now. Ultimately, Willy fails to fulfill his dream and the Requiem illustrates this point. “His funeral is certainly not like the grand one he had imagined, and he still remains misunderstood by his family. But death does not defeat Willy Loman. The Requiem proves that his memory will continue to live on in those who truly mattered to him while he was alive” (Centola). Willy Loman exmplifies the idea of the American Dream in the time of the 1940’s. The world was rapidly changing and people’s ideas and views of success were much different from what they had been before the time of WWII and The Great Depression. Arthur Miller paints us a vivid picture of the demands in society and the ways in which we can fall victim to these demands and expectations. Willy fails to fulfill his dream because he had “the wrong dream” and because he doesn’t know who he is. Being well-liked is not the measure of success, but rather hard work and dedication. Although Biff was told from an early age that as long as you are wellliked you will be successful, he still is able to uncover his own version of the American Dream and discover who he truly is. Willy Loman has and will remain an icon for generations to come and will always hold a spot in the heart of many men. People who had experienced what he did Amiro 12 during that time will continue to have Death of a Salesman hit close to home and bring them back into the time of their own American Dream. When considering the cultural context of the play, it is that much clearer to see the impact that society had on Willy, why he made the choices he did and how he tried to fulfill the American Dream. Willy Loman is the epitome of a failure. He has not only failed himself but he has failed his family, too. Without Willy’s fatal error in judgment, having the wrong dream, the play would not have had the same affect that it does. Although it can be argued that there are other contributing factors to his failure the hamartia is having the wrong dream. Being well-liked of being hard working and dedicated is what Willy values. Society has impacted him by making him think that he needs to get ahead in order to be successful. Times were demanding after The Great Depression and WWII and everyone needed to do what they could in order to survive. If only Willy had been more like Charley and Bernard he would have understood the true definition of success and ultimately reached the American Dream. But because Willy had the wrong dream he ends up taking his own life and leaving his family to pick up the pieces. Willy’s fatal flaw is the turning point for the downward action of the play and the main reason why he fails. Amiro 13 Works Cited Benziman, Galia. "Success, Law, and the Law of Success: Reevaluating Death of a Salesman's Treatment of the American Dream." South Atlantic Review 70.2 (2005): 20-40. JSTOR. Web. 24 Apr. 2012. Cardullo, Bert. "Death of a Salesman, life of a Jew: ethnicity, business, and the character of Willy Loman." Southwest Review 92.4 (2007): 583+. Literature Resource Center. Web. 19 Mar. 2012. Centola, Steven R. "Family Values in Death of a Salesman." CLA Journal 37.1 (Sept. 1993): 2941. Rpt. in Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Janet Witalec. Vol. 179. Detroit: Gale, 2004. Literature Resource Center. Web. 20 Mar. 2012. Lawrence, Stephen. “The Right Dream in Miller’s Death of a Salesman.” College English (1964): 547-549. National Council of Teachers of English. Vol. 25. JSTOR. Web. 17 Mar. 2012. Miller, Arthur. "Death of a Salesman." The Compact Bedford Introduction to Drama. Ed. Lee A. Jacobus. 6th ed. Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's, 2009. 704-41. Print. Murphy, Brenda. "Willy Loman: Icon of Business Culture." Michigan Quarterly Review 37.4 (Fall 1998): 755-766. Rpt. in Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Janet Witalec. Vol. 179. Detroit: Gale, 2004. Literature Resource Center. Web. 18 Mar. 2012. Amiro 14 Loeffelholz, Mary. "American Literature 1914-1945." The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Ed. Nina Baym. 7th ed. Vol. D. New York: W.W. Norton &, 2007. 1177-192. Print. Ribkoff, Fred. "Shame, Guilt, Empathy, and the Search for Identity in Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman." Modern Drama 43.1 (Spring 2000): 48-55. Rpt. in Contemporary Literary Criticism. Ed. Janet Witalec. Vol. 179. Detroit: Gale, 2004. Literature Resource Center. Web. 18 Mar. 2012. Ryan, James Gilbert., and Leonard C. Schlup. "The American Dream." Historical Dictionary of the 1940s. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2006. 22-23. Print.