About Archetypes

advertisement

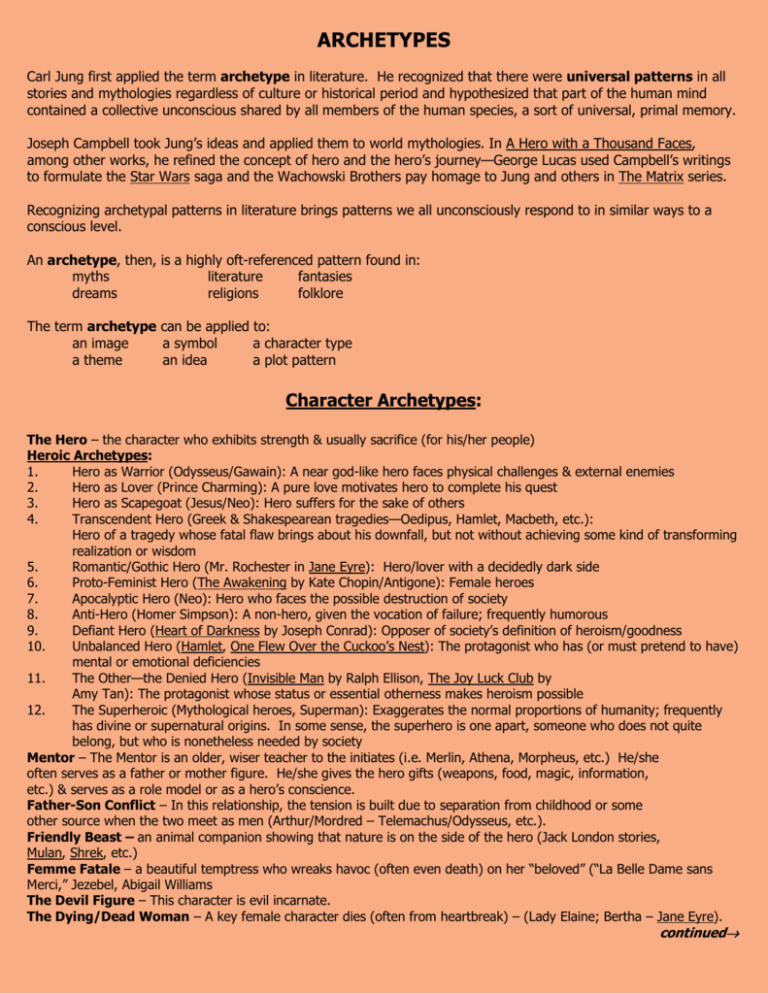

ARCHETYPES Carl Jung first applied the term archetype in literature. He recognized that there were universal patterns in all stories and mythologies regardless of culture or historical period and hypothesized that part of the human mind contained a collective unconscious shared by all members of the human species, a sort of universal, primal memory. Joseph Campbell took Jung’s ideas and applied them to world mythologies. In A Hero with a Thousand Faces, among other works, he refined the concept of hero and the hero’s journey—George Lucas used Campbell’s writings to formulate the Star Wars saga and the Wachowski Brothers pay homage to Jung and others in The Matrix series. Recognizing archetypal patterns in literature brings patterns we all unconsciously respond to in similar ways to a conscious level. An archetype, then, is a highly oft-referenced pattern found in: myths literature fantasies dreams religions folklore The term archetype can be applied to: an image a symbol a character type a theme an idea a plot pattern Character Archetypes: The Hero – the character who exhibits strength & usually sacrifice (for his/her people) Heroic Archetypes: 1. Hero as Warrior (Odysseus/Gawain): A near god-like hero faces physical challenges & external enemies 2. Hero as Lover (Prince Charming): A pure love motivates hero to complete his quest 3. Hero as Scapegoat (Jesus/Neo): Hero suffers for the sake of others 4. Transcendent Hero (Greek & Shakespearean tragedies—Oedipus, Hamlet, Macbeth, etc.): Hero of a tragedy whose fatal flaw brings about his downfall, but not without achieving some kind of transforming realization or wisdom 5. Romantic/Gothic Hero (Mr. Rochester in Jane Eyre): Hero/lover with a decidedly dark side 6. Proto-Feminist Hero (The Awakening by Kate Chopin/Antigone): Female heroes 7. Apocalyptic Hero (Neo): Hero who faces the possible destruction of society 8. Anti-Hero (Homer Simpson): A non-hero, given the vocation of failure; frequently humorous 9. Defiant Hero (Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad): Opposer of society’s definition of heroism/goodness 10. Unbalanced Hero (Hamlet, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest): The protagonist who has (or must pretend to have) mental or emotional deficiencies 11. The Other—the Denied Hero (Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison, The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan): The protagonist whose status or essential otherness makes heroism possible 12. The Superheroic (Mythological heroes, Superman): Exaggerates the normal proportions of humanity; frequently has divine or supernatural origins. In some sense, the superhero is one apart, someone who does not quite belong, but who is nonetheless needed by society Mentor – The Mentor is an older, wiser teacher to the initiates (i.e. Merlin, Athena, Morpheus, etc.) He/she often serves as a father or mother figure. He/she gives the hero gifts (weapons, food, magic, information, etc.) & serves as a role model or as a hero’s conscience. Father-Son Conflict – In this relationship, the tension is built due to separation from childhood or some other source when the two meet as men (Arthur/Mordred – Telemachus/Odysseus, etc.). Friendly Beast – an animal companion showing that nature is on the side of the hero (Jack London stories, Mulan, Shrek, etc.) Femme Fatale – a beautiful temptress who wreaks havoc (often even death) on her “beloved” (“La Belle Dame sans Merci,” Jezebel, Abigail Williams The Devil Figure – This character is evil incarnate. The Dying/Dead Woman – A key female character dies (often from heartbreak) – (Lady Elaine; Bertha – Jane Eyre). continued→ → The Scapegoat – An animal, or more usually a human, whose death in a public ceremony expiates some taint or sin of a community. They are often more powerful in death than in life. The Platonic Ideal – A woman who is a source of inspiration to the hero, who has an intellectual rather than a physical attraction to her. Star-Crossed Lovers – Two characters engaged in a love affair fated to end tragically for one or both due to the disapproval of society, friends, family, or some tragic situation (Pyramus/Thisbe, Lancelot/Guinevere, Romeo/Juliet). Symbolic Archetypes: Light vs. Darkness – Light usually suggests hope, renewal, or intellectual illumination; darkness implies the unknown, ignorance, or despair (Gothic [esp. Poe] stories) Nature vs. Mechanistic World – Nature is good while technology is evil (I, Robot by Isaac Asimov, “The World is Too Much With Us” by William Wordsworth, etc.) The Crossroads – A place or time of decision when a realization is made and change or penance results The Castle – A strong place of safety which holds treasure or princess, may be enchanted or bewitched (Shrek, Camelot, etc.) The Magic Weapon – The weapon the hero needs in order to complete his quest (Excalibur, David’s slingshot, Moses’ staff, etc.) Colors & Numbers - Color & number symbolism is extensive. Colors are probably familiar (i.e. red = blood, sacrifice, passion, danger or white = light, purity, innocence, death, horror, supernatural, etc.) Significant numbers are 3 (light, unity [holy trinity], male principle); 4 (circle, life cycle, four seasons, female principle); and 7 (most potent – signifying union of three and four – the completion of a cycle, perfect order, perfect number, religious symbol) Situational Archetypes: The Quest – What the hero must accomplish in order to bring fertility back to the wasteland, usually a search for some talisman, which will restore peace, order, and normalcy to a troubled land. The Journey – The journey sends the hero in search of some truth that will help save his kingdom. Types of Archetypal Journeys: 1. The quest for identity 2. The epic journey to find the promised land/to found the good city 3. The quest for vengeance 4. The warrior’s journey to save his people 5. The search for love (to rescue the princess/damsel in distress) 6. The journey in search of knowledge 7. The tragic quest: penance or self-denial 8. The fool’s errand 9. The quest to rid the land of danger 10. The grail quest (the quest for human perfection) “Crossing the Bar” – A character crosses water or a bridge often into the afterlife. (Greek mythology – the River Styx, Arthurian legends – the sea to Avalon, etc.) The Fall – The descent from a higher to lower state of being, usually as a punishment for transgression. It also involves the loss of innocence. “Cinderella/Rags-to-Riches” Story – The plot involves a lowly character who rises to some form of greatness. Death and Rebirth – The most common of all situational archetypes, this motif grows out of a parallel between the cycle of nature and the cycle of life (see Dylan Thomas’s “Fern Hill”/John Keats’s “On the Grasshopper & the Cricket”). Thus morning and springtime represent birth, youth, or rebirth, while evening and winter suggest old age or death. Battle between Good and Evil – A battle between two primal forces. Mankind shows eternal optimism in the continual portrayal of good triumphing over evil despite great odds. Sibling Rivalry – Tension between siblings; sometimes jealousy, “battle” for approval, etc. (Cain & Abel, Cinderella’s stepsisters, etc.) The Unhealable Wound – Either a physical or psychological wound that cannot be fully healed (Lancelot’s or the Fisher King’s, Anse Bundren’s “teeth,” etc.) ALLUSIONS Notice that archetypes are often referred to in various ways and places in culture (in literature, in film, in art, in pop culture, etc.) *For proof, watch for TONS of these references in such films as Shrek, Star Wars films, and The Matrix series. References to well-known people, places, events (real or fictional) or to works of art have a special name; they are called allusions (from the verb “to allude” which means “to refer to”). An allusion is a type of figurative language that uses its referent as the point with which we make associations to paint pictures in our minds. Therefore, if you miss the referent, you can’t see the whole picture a writer is trying to show you. (This is one major factor behind cultural literacy, the knowledge of various archetypes and less-familiar images in culture; because the stronger your cultural literacy, the more “big pictures” you’re able to see). Sometimes, even, an image is impossible to interpret without knowledge of an allusion that’s present. Allusions fall into four basic categories: Biblical (references to major events, people, and places in the bible) – i.e. reference to the Good Samaritan Historical (references to major events, people, and places in history) – i.e. reference to the Vietnam War, to slavery, to Napolean, to Florence Nightengale, etc. Literary ([fictional] references to major events, people, and places in literature – often Shakespearean) – i.e. reference to Poe’s raven, to Jane & Rochester’s tree (Jane Eyre), to feuding families, to Camelot, etc. & Mythological ([fictional] references to major events, people, and places in [Greek/Roman] Mythology) – i.e. reference to Hercules, to Achilles, to Aphrodite/Venus, etc. Also, some allusions are related to works or art (music or art) or to elements in contemporary (aka “Popular/Pop”) Culture. Examples: superhero allusions (i.e. Superman, Batman, etc.) allusions to great composers’ works (i.e. Beethoven’s 5th) “ to major art pieces (i.e. DaVinci’s Mona Lisa, Monet’s Waterlilies, etc.) “ to performers (i.e. Elvis, The Beatles, Madonna, etc.) “ to theatrical or cinematic productions (i.e. The Wizard of Oz) “ to contemporary events (i.e. Bill & Monica, the 9-11 tragedy, etc.) Bottom line: Pay attention to allusions (references) in what you read and see, because deciphering them allows you to gain MUCH more insight into and appreciation for the world around you