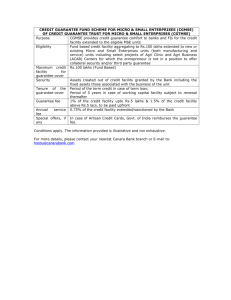

giz study on smes credit guarantee schemes

advertisement