the critical role of global food consumption patterns in achieving

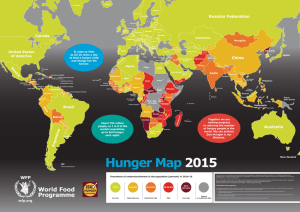

advertisement