dr-thesis-2013-Bo-Byrkjeland

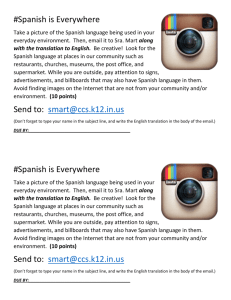

advertisement