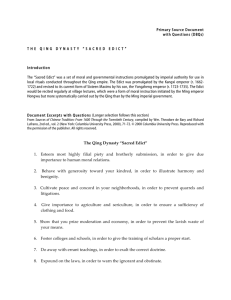

The Edict of Milan - CEC-CSC - Conference of European Churches

advertisement

The Edict of Milan (313-2013): a Basis for Freedom of Religion or Belief? Opening Address Metropolitan Emmanuel of France Novi Sad (Serbia) May 3rd 2012 Your Beatitude, Patriarch Irinej Your Eminences, Your Excellencies, Dear Bishop Irinej of Backa Honorable Representative of the Serbian Government, Mr. Bogoljub Sijakovic Honorable President of the Government of Vojvodine, Mr. Bojan Pajtic Doctor Johann Marte, President of the Foundation Pro Oriente Dear Mr. Boris Vukobrat, President of the Peace and Crises Management Foundation Dear Mme Mirjana Prlhevic, Secretary General of the International Association CIVI Dear Elisabeta Kitanovic Ladies and Gentlemen, Dear Friends, To celebrate a jubilee is like celebrating an anniversary. We take the time to return to the events of the past, in order to better consider our present, and to consider the situation itself, as well as the directives we may identify for our future. Next year, the Edict of Milan will celebrate its 1,700 t h jubilee or anniversary, and its tenets are as relevant today as they were then. Let us first take a look at the position of the Edict of Milan, not only in the history of Christianity, but in human history in general. Let me read something to you that I came across: “. . . for the sake of the peace of our times, that each one may have the free opportunity to worship as he pleases . . .” 1 (Edict of Milan, §1). This quote could have been printed in this morning’s newspaper, yet it is taken from the English translation of the Edict of Milan in the year 313. When he co-issued the Edict, St. Constantine the Great was a pagan ruler. The same hand that signed this freedom of religion mandate into law, had also signed orders carrying out executions and persecutions. Yet, somehow he had a change of heart. This reality causes us to have hope for peace in the world because the personal and institutional religious inclinations of rulers do not necessarily dictate their ability to act on behalf of the minority religions under their jurisdiction. In Ephesians 1:11 we learn that “In Him also we have obtained an inheritance, being predestined according to the purpose of Him who works all things according to the counsel of His will . . .” Perhaps, Christ’s concern for humanity is reflected in the decisions of leaders who do not confess Christianity, yet act according to the counsel of His will for the greater good of all God’s people. What difference in the historical record has the Edict of Milan made? It remains an important milestone in the plan of the development of ideas through 17 centuries. The character and spirit of the edict of Milan is more so an act of recognition of freedom in the pluralism of opinions and confessions rather than just an edict of religious tolerance. There is within this idea a subtle difference that completely changes the trajectory of the discussion. Comparing the concept of religious tolerance to pluralism of opinions and confessions is like comparing something which is substandard to us with something which is equal to us. According to the dictionary, the word tolerate is derived from a Latin word for “to bear”. So, to merely tolerate another puts one in a superior position, that is, we are choosing to overlook their ‘faults’ and ‘bear’ them. On the other hand, the definition of pluralism is “a theory that there is more than one basic substance or principle.” If we have the view that there is more than one basic substance or principle, we see a greater value for individual identity and choice. Quite often we quote the following phrase from the famous edict, acknowledging to each person the possibility to, and I quote: “worship in his or her manner the divinity that is in the heavens”. The wisdom in this concept provides humanity with an antidote to war, persecution, and hatred. It must be emphasised that acknowledgement of the existence of “more than one basic substance or principle” does not constitute syncretism, but allows others to determine for themselves what substance and principle holds meaning for them. The contentions caused by viewing others as needing to be tolerated, or even to be more tolerant, are damaging to the human respect needed to live in peace. For this reason, we see that the governments of our planet consecrate an ever increasing amount of attention and intensity on such issues. And I will mention here only as an example the Commission on Religious Freedoms of the Secretary of State of the USA. The very existence of such a body must concern us in two ways. On the one hand the existence of such a commission serves as recognition of the need for expertise on this subject, in view of the global implementation of human rights. On 2 the other hand, it is the flip side, namely the existence of such a commission which speaks to violations against religious freedom which have become more and more prevalent. These violations of religious rights constitute an inalienable dimension of this contemporary geopolitical issue. Think with me about this: Do religious rights exist because governments, leaders, or commissions declare that they do, or do they exist whether or not they are recognised by governments, leaders, or commissions? Did not the freedom to follow one’s own conscience emerge in the Garden of Eden when God told Adam and Eve not to eat of the fruit, but they did so anyway? God did not control their thoughts or actions through threats, imprisionment, persection, or executions. Without wading into the deep waters of hard determinism versus metaphysical libertarianism, there is in the story of Adam and Eve a framework for freedom of choice within Christian doctrine. Reflected within this framework of Christian theology, we find not only freedom of personal choice, but how to approach another who does things you wished they did not do. This theology can inform and support international relations in that we recognise another and approach them with deep respect. For within religious freedom we discover not only the expression of this freedom, but also the interpersonal dimension that reveals the intrinsic links that unite humanity, creation, and the States. His All Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, in the footsteps of the Apostle Andrew has spoken truth with regards to religious freedom as understood from a purely individual perspective. He has stressed the idea that freedom and religious freedom, a fortiori, cannot be taken into consideration in an isolated manner; they can be deployed only within a relational sphere. Patriarch Bartholomew insists that: "We cannot be truly free unless we are part of a community of free persons. Freedom is never alone but always social. [...] In turning one’s back, in refusing to share is to lose freedom. Freedom is expressed in socialization (In Search of the Mystery, 2010, p. 176)”. It is due to this kind of commitment to our vision that the Orthodox Church will be recognized on May 12 when the Ecumenical Patriarch receives the Medal of Religious Freedom awarded by the Roosevelt Stichting Foundation for commitment in favour of the reconciliation through interfaith dialogue. We have witnessed a sustained effort in recent decades on the part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and other major religions to come face to face and engage in interreligious and ecumenical dialogue. The creation of an Ecumenical Charter is the result of many long hours of discussion between representatives seeking to live in peace and unity. For its part, the Ecumenical Charter emphasises the importance of religious freedom by stating: "We commit ourselves that every person can freely choose his or her religious and church affiliation as a matter of conscience" (§2). This commitment is also one of the commitments of the Conference of European Churches, to which religious freedom is an inalienable right. It seems important to me to recognize how Christianity is related to the Edict of Milan, not only as an object, but especially more 3 so as a subject of this freedom brought by St. Constantine the Great. Therefore, it is only appropriate that the various Christian families reinvest in the field of freedom in order to give a stronger sense to its scriptural and theological sources that are summed up perfectly in the phrase of St. Maximus the Confessor in the 7t h century: "Created in the image of God, men are free by nature”. At the crossroads of these two approaches where individual freedom cannot be developed except in a relational form, it is solidarity that responds most appropriately to the changes of our contemporary world. At a European level, the first of these changes has been crystallized around the formation of a multicultural pluralism, reinforced within the European Union with the free movement of people. Migration from outside Europe also comes into play as a dynamic reconfiguration of the distinctive European identity. However, tensions that emerge from European pluralism should not cause us to lose sight of our commitment to peace through religious freedom and dialogue. It was for peace that the Edict of Milan was created. May peace be realised in Europe and throughout the world. Dear friends, Please allow me, on behalf of the Conference of European Churches, to congratulate you for the organization of such an event. I would also like to express my heart felt gratitude to your Beatitude for your blessing for this gathering; to Bishop Irinej of Backa for hosting it; and to all the people that contributed to the coordination and execution of this conference. As the president and the Council of European Churches, I assure you that we are with you all as participants and we stand with the Serbian people in their work toward peace and religious freedom. We support your efforts, in the spirit of friendship and in prayer. I am convinced that our dialogue today will allow us to delve even further into the conditions of religious freedom posed by the Edict of Milan. Admittedly, 1700 years have passed since this proclamation; nevertheless, its relevance continues to be felt since religious freedom is still violated with increasing intensity. Is the Edict of Milan the basis for freedom of religion or belief, or a divinely inspired declaration of humanity’s God-ordained state? Either way, “. . . for the sake of the peace of our times”, let us work toward a day when “each one may have the free opportunity to worship as he pleases . . .” (Edict of Milan, §1). In the spirit of St. Paul writing to the Romans, “. . . peace be with you all” (Romans 15:33). Thank you. 4