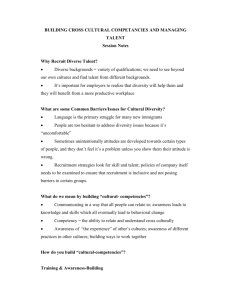

Cultivating effective corporate cultures.

advertisement