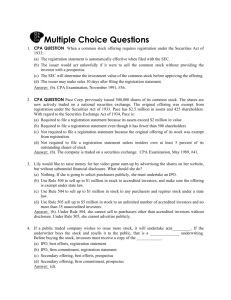

Legal and Regulatory Aspects of Marketing and Promoting Private

advertisement