External speakers in higher education institutions

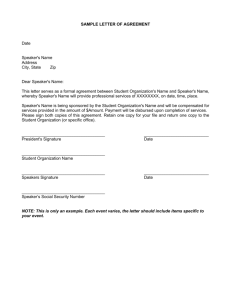

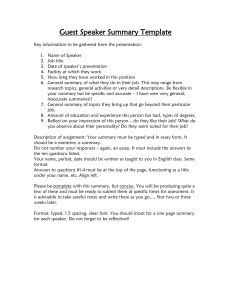

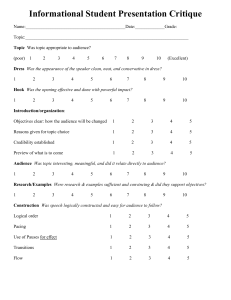

advertisement