Unocal Corp. v. Mesa Petroleum Co. and the All

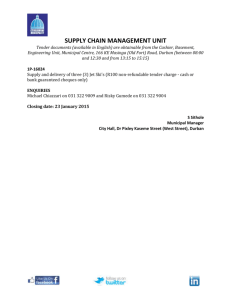

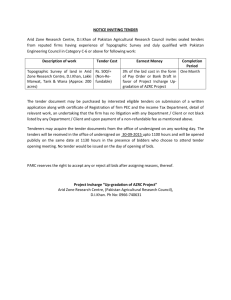

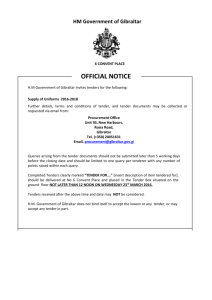

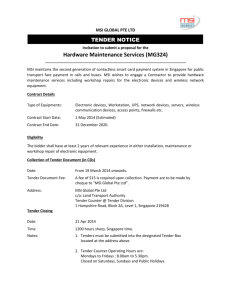

advertisement