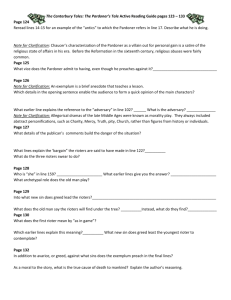

General Prologue At the Tabard Inn, a tavern in Southwark, near

advertisement