Literary Terms - Academic Home Page

advertisement

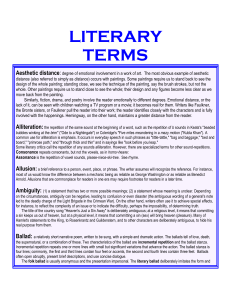

Literary Terms Lilia Melani LITERARY TERMS Aesthetic distance (also called distance): degree of emotional involvement in a work of art. The most obvious example of aesthetic distance (also referred to simply as distance) occurs with paintings. Some paintings require us to stand back to see the design of the whole painting; standing close, we see the technique of the painter, say the brush strokes, but not the whole. Other paintings require us to stand close to see the whole; their design and any figures become less clear as we move back from the painting. Similarly, fiction, drama, and poetry involve the reader emotionally to different degrees. Emotional distance, or the lack of it, can be seen with children watching a TV program or a movie; it becomes real for them. Writers like Dickens, the Brontë sisters, or Faulkner pull the reader into their work; the reader identifies closely with the characters and is fully involved with the happenings. Hemingway, on the other hand, maintains a greater emotional distance from the reader. Alliteration: the repetition of the same sound at the beginning of a word, such as the repetition of b sounds in Keats's "beaded bubbles winking at the brim" ("Ode to a Nightingale") or Coleridge's "Five miles meandering in a mazy motion ("Kubla Khan"). A common use for alliteration is emphasis. It occurs in everyday speech in such phrases as "tittle-tattle," "bag and baggage," "bed and board," "primrose path," and "through thick and thin" and in sayings like "look before you leap." Some literary critics call the repetition of any sounds alliteration. However, there are specialized terms for other sound-repetitions. Consonance repeats consonants, but not the vowels, as in “horror”and “hearer.” Assonance is the repetition of vowel sounds, “please” and “niece,” “ski” and “tree.” See rhyme. An allusion: a brief reference to a person, event, place, or phrase. The writer assumes will recognize the reference. For instance, most of us would know the difference between a mechanic's being as reliable as George Washington or as reliable as Benedict Arnold. Allusions that are commonplace for readers in one era may require footnotes for readers in a later time. Ambiguity: (1) a statement which has two or more possible meanings; (2) a statement whose meaning is unclear. Depending on the circumstances, ambiguity can be negative, leading to confusion or even disaster (the ambiguous wording of a general's note led to the deadly charge of the Light Brigade in the Crimean War). On the other hand, writers often use it to achieve special effects, for instance, to reflect the complexity of an issue or to indicate the difficulty, perhaps the impossibility, of determining truth. The title of the country song "Heaven's Just a Sin Away" is deliberately ambiguous; at a religious level, it means that committing a sin keeps us out of heaven, but at a physical level, it means that committing a sin (sex) will bring heaven (pleasure). Many of Hamlet's statements to the King, to Rosenkrantz and Guildenstern, and to other characters are deliberately ambiguous, to hide his real purpose from them. Ballad: a relatively short narrative poem, written to be sung, with a simple and dramatic action. The ballads tell of love, death, the supernatural, or a combination of these. Two characteristics of the ballad are incremental repetition and the ballad stanza. Incremental repetition repeats one or more lines with small but significant variations that advance the action. The ballad stanza is four lines; commonly, the first and third lines contain four feet or accents, the second and fourth lines contain three feet. Ballads often open abruptly, present brief descriptions, and use concise dialogue. The folk ballad is usually anonymous and the presentation impersonal. The literary ballad deliberately imitates the form and spirit of a folk ballad. The Romantic poets were attracted to this form, as Longfellow with "The Wreck of the Hesperus," Coleridge with the "Rime of the Ancient Mariner" (which Page 2 of 7 is longer and more elaborate than the folk ballad) and Keats with "La Belle Dame sans Merci" (which more closely resembles the folk ballad). Characterization: the way an author presents characters. In direct presentation, a character is described by the author, the narrator or the other characters. In indirect presentation, a character's traits are revealed by action and speech. Characters can be discussed in a number of ways. • The protagonist is the main character, who is not necessarily a hero or a heroine. The antagonist is the opponent; the antagonist may be society, nature, a person, or an aspect of the protagonist. The antihero, a recent type, lacks or seems to lack heroic traits. • A persona is a fictional character. Sometimes the term means the mask or alter-ego of the author; it is often used for first person works and lyric poems, to distinguish the writer of the work from the character in the work. • Characters may be classified as round (three-dimensional, fully developed) or as flat (having only a few traits or only enough traits to fulfill their function in the work); as developing (dynamic) characters or as static characters. • A foil is a secondary character who contrasts with a major character; in Hamlet, Laertes and Fortinbras, whose fathers have been killed, are foils for Hamlet. Convention: (1) a rule or practice based upon general consent and upheld by society at large; (2) an arbitrary rule or practice recognized as valid in any particular art or discipline, such as literature or art (NED). For example, when we read a comic book, we accept that a light bulb appearing above the head of a comic book character means the character suddenly got an idea. • Literary convention: a practice or device which is accepted as a necessary, useful, or given feature of a genre, e.g., the proscenium stage (the "picture-frame" stage of most theaters), a soliloquy, the epithet or boast in the epic (which those of you who took any Classics courses will be familiar with). • Stock character: character types of a genre, e.g., the heroine disguised as a man in Elizabethan drama, the confidant, the hardboiled detective, the tightlipped sheriff, the girl next door, the evil hunters in a Tarzan movie, ethnic or racial stereotypes, the cruel stepmother and Prince Charming in fairy tales. • Stock situation: frequently recurring sequence of action in a genre, e.g., rags-to-riches, boy-meetsgirl, the eternal triangle, the innocent proves himself or herself. • Stock response: a habitual or automatic response based on the reader's beliefs or feelings, rather than on the work itself. A moralistic person might be shocked by any sexual scene and condemn a book or movie as dirty; a sentimentalist is automatically moved by any love story, regardless of the quality of the writing or the acting; someone requiring excitement may enjoy any violent story or movie, regardless of how mindless, unmotivated or brutal the violence is. Fiction: prose narrative based on imagination, usually the novel or the short story. Genre: a literary species or form, e.g., tragedy, epic, comedy, novel, essay, biography, lyric poem. Genre is a French term derived from the Latin genus, generis, meaning "type," "sort," or "kind." Works in a genre are classified according to what they have in common, either in their formal structures or in their treatment of subject matter, or both. All of the arts recognize genres: in painting, there are the landscape, the still life, the portrait; in music there are the sonata, the symphony, the song; in film and on television, we have the domestic comedy, the horror movie, the thriller, the Western, the musical, the love story. Page 3 of 7 Irony: the discrepancy between what is said and what is meant, what is said and what is done, what is expected or intended and what happens, what is meant or said and what others understand. Sometimes irony is classified into types: • in situational irony, expectations aroused by a situation are reversed; • in cosmic irony or the irony of fate, misfortune is the result of fate, chance, or God; • in dramatic irony. the audience knows more than the characters in the play, so that words and action have additional meaning for the audience; • Socractic irony is named after Socrates' teaching method, whereby he assumes ignorance and openness to opposing points of view which turn out to be (he shows them to be) foolish. Click here for examples of irony. Irony is often confused with sarcasm and satire: • Sarcasm is one kind of irony; it is praise which is really an insult; sarcasm generally involves malice, the desire to put someone down, e.g., "This is my brilliant son, who failed out of college." • Satire is the exposure of the vices or follies of an individual, a group, an institution, an idea, a society, etc., usually with a view to correcting it. Satirists frequently use irony. Language can be classified in a number of ways. • Denotation: the literal meaning of a word; there are no emotions, values, or images associated with denotative meaning. Scientific and mathematical languages carry few, if any emotional or connotative meanings. • Connotation: the emotions, values, or images associated with a word. The intensity of emotions or the power of the values and images associated with a word varies. Words connected with religion, politics, and sex tend to have the strongest feelings and images associated with them. For most people, the word mother calls up very strong positive feelings and associations--loving, self-sacrificing, always there for you, understanding; the denotative meaning, on the other hand, is simply "a female animal who has borne one or more children." Of course connotative meanings do not necessarily reflect reality; for instance, if someone said, "His mother is not very motherly," you would immediately understand the difference between motherly (connotation) and mother (denotation). • Abstract language refers to things that are intangible, that is, which are perceived not through the senses but by the mind, such as truth, God, education, vice, transportation, poetry, war, love. Concrete language identifies things perceived through the senses (touch, smell, sight, hearing, and taste), such as soft, stench, red, loud, or bitter. • Literal language means exactly what it says; a rose is the physical flower. Figurative language changes the literal meaning, to make a meaning fresh or clearer, to express complexity, to capture a physical or sensory effect, or to extend meaning. Figurative language is also called figures of speech. The most common figures of speech are these: * A simile: a comparison of two dissimilar things using "like" or "as", e.g., "my love is like a red, red rose" (Robert Burns). * A metaphor: a comparison of two dissimilar things which does not use "like" or "as," e.g., "my love is a red, red rose" (Lilia Melani). * Personification: treating abstractions or inanimate objects as human, that is, giving them human attributes, powers, or feelings, e.g., "nature wept" or "the wind whispered many truths to me." Page 4 of 7 * Hyperbole: exaggeration, often extravagant; it may be used for serious or for comic effect. * Apostrophe: a direct address to a person, thing, or abstraction, such as "O Western Wind," or "Ah, Sorrow, you consume us." Apostrophes are generally capitalized. * Onomatopoeia: a word whose sounds seem to duplicate the sounds they describe--hiss, buzz, bang, murmur, meow, growl. * Oxymoron: a statement with two parts which seem contradictory; examples: sad joy, a wise fool, the sound of silence, or Hamlet's saying, "I must be cruel only to be kind" • Elevated language or elevated style: formal, dignified language; it often uses more elaborate figures of speech. Elevated language is used to give dignity to a hero (note the speeches of heroes like Achilles or Agamemnon in the Iliad), to express the superiority of God and religious matters generally (as in prayers or in the King James version of the Bible), to indicate the importance of certain events (the ritual language of the traditional marriage ceremony), etc. It can also be used to reveal a self-important or a pretentious character, for humor and/or for satire. Lyric Poetry: a short poem with one speaker (not necessarily the poet) who expresses thought and feeling. Though it is sometimes used only for a brief poem about feeling (like the sonnet).it is more often applied to a poem expressing the complex evolution of thoughts and feeling, such as the elegy, the dramatic monologue, and the ode. The emotion is or seems personal In classical Greece, the lyric was a poem written to be sung, accompanied by a lyre. Meter: a rhythm of accented and unaccented syllables which are organized into patterns, called feet. In English poetry, the most common meters are these: • Iambic: a foot consisting of an unaccented and accented syllable. Shakespeare often uses iambic, for example the beginning of Hamlet's speech (the accented syllables are italicized), "To be or not to be.” Listen for the accents in this line from Marlowe, "Come live with me and be my love." English seems to fall naturally into iambic patterns, for it is the most common meter in English. • Trochaic: a foot consisting of an accented and unaccented syllable. Longfellow's Hiawatha uses this meter, which can quickly become singsong (the accented syllable is italicized): "By the shores of GitcheGumee By the shining Big-Sea-water." The three witches' speech in Macbeth uses it: "Double, double, toil and trouble." • Anapestic: a foot consisting of two unaccented syllables and an accented syllable. These lines from Shelley's Cloud are anapestic: "Like a child from the womb, like a ghost from the tomb I arise and unbuild it again." • Dactylic: a foot consisting of an accented syllable and two unaccented syllables, as in these words: swimingly, mannikin, openly. • Spondee: a foot consisting of two accented syllables, as in the word heartbreak. In English, this foot is used occasionally, for variety or emphasis. • Pyrrhic: a foot consisting of two unaccented syllables, generally used to vary the rhythm. Page 5 of 7 A line is named for the number of feet it contains: monometer: one foot, dimeter: two feet, trimeter: three feet, tetrameter: four feet, pentameter: five feet, hexameter: six feet, heptameter: seven feet. The most common metrical lines in English are tetrameter (four feet) and pentameter (five feet). Shakespeare frequently uses unrhymed iambic pentameter in his plays; the technical name for this line is blank verse. In this course, I will not be asking you to identify meters and metrical lines, but I would like you to have some awareness of their existence. Modern English poetry is metrical, i.e., it relies on accented and unaccented syllables. Not all poetry does; Anglo-Saxon poetry relied on a system of alliteration. Skillful poets rarely use one meter throughout a poem but use these meters in combinations; however, a poem generally has one dominant meter. Ode: usually a lyric poem of moderate length, with a serious subject, an elevated style, and an elaborate stanza pattern. There are various kinds of odes, which we don't have to worry about in an introductory course like this. The ode often praises people, the arts of music and poetry, natural scenes, or abstract concepts. The Romantic poets used the ode to explore both personal or general problems; they often started with a meditation on something in nature, as did Keats in "Ode to a Nightingale" or Shelley in"Ode to the West Wind." Paradox: a statement whose two parts seem contradictory yet make sense with more thought. Christ used paradox in his teaching: "They have ears but hear not." Or in ordinary conversation, we might use a paradox, "Deep down he's really very shallow." Paradox attracts the reader's or the listener's attention and gives emphasis. Point of view: the perspective from which the story is told. • The most obvious point of view is probably first person or "I." • The omniscient narrator knows everything, may reveal the motivations, thoughts and feelings of the characters, and gives the reader information. • With a limited omniscient narrator, the material is presented from the point of view of a character, in third person. • The objective point of view presents the action and the characters' speech, without comment or emotion. The reader has to interpret them and uncover their meaning. A narrator may be trustworthy or untrustworthy, involved or uninvolved. Rhyme: the repetition of similar sounds. In poetry, the most common kind of rhyme is end rhyme, which occurs at the end of two or more lines. Internal rhyme occurs in the middle of a line, as in these lines from Coleridge, "In mist or cloud, on mast or shroud" or "Whiles all the night through fog-smoke white" ("The Ancient Mariner"). There are many kinds of end rhyme: • True rhyme is what most people think of as rhyme; the sounds are nearly identical--notion, motion, potion, for example. • Weak rhyme, also called slant, oblique, approximate, or half rhyme, refers to words with similar but not identical sounds, e.g., “notion” and “nation,” “ bear” and “bore,” “ear” and “are.” Emily Dickinson frequently uses such partial rhymes. • Eye rhyme occurs when words look alike but don't sound alike--e.g., “bear” and “ear.” Sonnet: a lyric poem consisting of fourteen lines. In English, generally the two basic kinds of sonnets are the Italian or Petrarchan sonnet and the Shakespearean or Elizabethan sonnet. The Italian/Petrarchan sonnet is named after Petrarch, an Italian Renaissance poet. The Petrarchan sonnet consists of an octave (eight lines) and a sestet (six lines). The Shakespearean sonnet consists of three quatrains (four lines each) Page 6 of 7 and a concluding couplet (two lines). The Petrarchan sonnet tends to divide the thought into two parts; the Shakespearean, into four. Structure: framework of a work of literature; the organization or over-all design of a work. The structure of a play may fall into logical divisions and also a mechanical division of acts and scenes. Groups of stories may be set in a larger structure or frame, like The Canterbury Tales, The Decameron, or One Thousand and One Nights (also known as The Arabian Nights). Style: manner of expression; how a speaker or writer says what he says. Notice the difference in style of the opening paragraphs of Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms and Mark Twain's The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterward the road bare and white except for the leaves. A Farewell to Arms You don't know about me without you have read a book by the name of The Adventures of Tom Sawyer; but that ain't no matter. That book was made by Mr. Mark Twain, and he told the truth, mainly. There was things which he stretched, but mainly he told the truth. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Symbol: in general terms, anything that stands for something else. Obvious examples are flags, which symbolize a nation; the cross is a symbol for Christianity; Uncle Sam a symbol for the United States. In literature, a symbol is expected to have significance. Keats starts his ode with a real nightingale, but quickly it becomes a symbol, standing for a life of pure, unmixed joy; then before the end of the poem it becomes only a bird again. Tone: the writer's attitude toward and feelings about the material and/or readers. Tone may be playful, formal, intimate, angry, serious, ironic, outraged, baffled, tender, serene, depressed, etc. or some combination of these. Theme: (1) the abstract concept explored in a literary work; (2) frequently recurring ideas, such as enjoylife while-you-can; (3) repetition of a meaningful element in a work, such as references to sight, vision, and blindness in Oedipus Rex. Sometimes the theme is also called the motif. Themes in Hamlet include the nature of filial duty and the dilemma of the idealist in a non-ideal situation. A theme in Keats's "Ode to a Nightingale" is the difficulty of correlating the ideal and the real. Tragedy: broadly defined, a literary and particularly a dramatic presentation of serious actions in which the chief character has a disastrous fate. There are many different kinds and theories of tragedy, starting with the Greeks and Aristotle's definition in The Poetics, "the imitation of an action that is serious and also, as having magnitude, complete in itself...with incidents arousing pity and fear, wherewith to accomplish its catharsis of such emotions." In the Middle Ages, tragedy merely depicted a decline from happiness to misery because of some flaw or error of judgment. Page 7 of 7