Creating Alpha While Minimizing Beta

Creating Alpha While Minimizing Beta

Eric G. Flamholtz, Ph.D.

Two constructs that are commonly used in investment parlance are “ Alpha ” and “ Beta .”

These are statistical measurements used in modern portfolio theory.

Alpha is the differential excess return (positive or negative) of an investment relative to the return of a benchmark index. It is the “abnormal” rate of return on a security or portfolio in excess of what would be predicted by an equilibrium model like the capital asset pricing model. A positive alpha of 1.0 means the investment has outperformed its benchmark index by 1%. Correspondingly, a similar negative Alpha would indicate an underperformance of

1%.

Beta is a measure of the volatility, or systematic risk, of a security or a portfolio in comparison to the market as a whole. It leads to the statement “high risk, high (expected) return”. For example, US treasuries are presumed to be a riskless asset, and therefore the return is lower than risk assets such as corporate equities. A “Beta” of less than 1 indicates that the security will be less volatile than the market. A Beta of greater than 1 indicates that the security's price will be more volatile than the market. For example, if a stock's Beta is

1.2, it's theoretically 20% more volatile than the market.

According to Richard Bernstein, a prominent Wall Street strategist, there are two types of active equity managers: Alpha managers and Beta Managers.

1

Alpha managers try to select individual financial assets (stock, fixed income, even private companies) that will outperform their benchmark. Beta managers select securities in relation to a target level of risk.

The Determinants of Alpha and Beta

But the question remains: How are companies which outperform their benchmarks

(“benchmark outperforming companies”) created? First it is critical to note that benchmark outperforming companies are created by managerial action, not by investment professionals.

What do managers do to create a company with incremental alpha and/or reduced

Beta than their comparison companies

2

?

The answer is that they use a superior approach to building sustainably successful organizations such as the one we have developed and described previously.

3 Using this approach gives these companies sustainable competitive advantages . It is these sustainable competitive advantages that are the determinants of incremental alpha and beta.

Creating Alpha: The Example of PowerBar

PowerBar, which is now owned by Nestle, was a company founded by Brian and Jennifer

Maxwell. In 1996, Brian Maxwell, who was aware of the work that our firm Management

1

2

3

See Lawrence C. Strauss, “Betting that the U.S. Will Beat Emerging Markets,” Barron’s June 10, 2013, p. 39.

It is theoretically possible to create incremental alpha and reduced beta simultaneously !

See Eric G. Flamholtz and Yvonne Randle , Growing pains: Transitioning for Entrepreneurship to a Professionally

Managed Firm , Jossey-Bass publishers, Inc. 2007.

Systems did for Starbucks during its early years (as described in Howard Schultz’s book), invited me to serve as an advisor and assist with PowerBar’s organizational development.

4

Our firm worked with PowerBar from approximately 1996 to 2000.

During that period, we assisted PowerBar’s organizational development in several ways including:

These initiatives are described in the tools section of our web site.

6

The Bottom Line

The bottom line impact of organizational development can be seen in the differential value of PowerBar over the period of these initiatives. In 1997, a private equity firm that wanted to invest in PowerBar placed a value of one times sales on the company. This offer was rejected by Brian Maxwell.

Company sales reached $150 million before it was sold to Nestle in 2000 for $375 million or

2.5 time’s sales. The incremental value (or alpha) that developed over the three year period can be measured by the difference in valuation multiple (from 1.0 time sales to 2.5 times sales or 1.5). At the same time that alpha was increasing beta was decreasing, because the company was developing its infrastructure, as measured by our survey instruments

(described below).

Identifying Benchmark Outperforming Companies

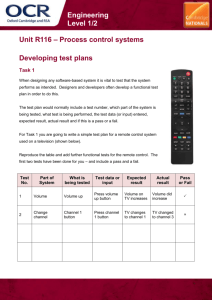

How can we identify potential benchmark outperforming Companies? We have developed a set of surveys which can be used to identify such companies. These are the Growing Pains

Survey© and our Organizational Effectiveness Survey©.

Both are validated surveys and both have been empirically tested as predictors of financial performance.

7

We have developed benchmark scores that enable us determine different levels of strategic organizational development that are statistically linked to financial performance as well as the risk of underperformance and possible failure. Scores for “Strategic

4 See Howard Schultz and Dori Jones Yang, Pour Your Heart into It: How Starbucks Built a Company one Cup at a

Time, Hyperion, 1997.

5

See www.mgtsystems.com/What We Do/Organizational Assessment.

6

See www.mgtsystems.com.

7

See Eric G. Flamholtz , “Towards an Integrative Theory of Organizational Success and Failure: Previous Research and Future issues,” International Journal of Entrepreneurship Education, Vol. 1, Issue 3, 2002-03, pp. 297-319

Organizational Development” are a measure of potential Alpha, while scores of “Growing

Pains” are a measure of potential Beta or risk.

The strategic development benchmark scores enable us to classify companies in five levels:

1) Business champions (best of breed), 2) Leading companies, 3) sustainably successful companies, 4) marginally successful companies, and 5) companies at risk. The growing pains scores are inversely related to financial performance. Companies are color-coded at five levels according to the degree of growing pains: green, yellow, orange, red, and purple. The colors range from “healthy” (green) to “at risk of bankruptcy” (purple).