The Executive Branch

advertisement

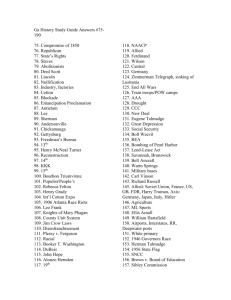

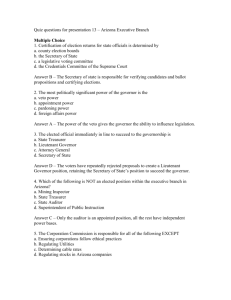

The Executive Branch There are six statewide executive officials elected in the state of Missouri, all of whom serve four-year terms. Though each of these officials heads an office of several employees, by far the largest number of executive branch employees are in the 15 executive departments and the Office of Administration. Each of these departments is headed by either a Director or a multimember Commission, appointed by the governor with the approval of the Senate. (Typically, the terms of the members of the commissions are both specific and staggered, and the commissions must be bipartisan.) These appointees don’t really constitute a “cabinet” per se, though the governor interacts with them in varying degrees to try to coordinate policy. Governors typically can exercise more influence over departments headed by a director than those headed by a commission. Directors generally serve at the pleasure of the Governor, in contrast to commissions, whose definite terms of service and bipartisan nature may mean that they are better equipped to insulate the department from direct political pressure from the Governor. The size of the departments ranges from about 300 employees in the Department of Agriculture, to about 11,150 in the Department of Corrections. (The Department of Higher Education has over 27,000 employees, counting all of the employees of the public four-year colleges and universities.)i Most of the employees of state government are hired through a merit system, though there is a small percentage hired through the patronage system of political appointment. Most patronage employees are found in the Departments of Agriculture and Revenue. Missouri Executive Departments Agriculture Conservation* Corrections Economic Development Elementary and Secondary Education* Health and Senior Services Higher Education* Insurance, Financial Institutions, and Professional Registration Labor and Industrial Relations* Mental Health* Natural Resources Public Safety Revenue Social Services Transportation* Office of Administration * Departments headed by a multimember commission. All others are headed by individual directors. Governor The position of governor in the state of Missouri is fairly comparable to that in other states. The constitution establishes age, citizenship, and residency qualifications for the office, and spells out some of the formal powers of the position. Those include a broad appointment power for executive officials and members of almost 200 regulatory or advisory boards or commissions (and some judges, subject to the state’s Nonpartisan Court Plan, discussed below), the power to remove executive appointees, the power as commander-in-chief of the state militia, the clemency power (the power to issue pardons, reprieves, and commutations), the power to call the legislature into special session, and the power to veto pieces of legislation, subject to an override by 2/3 vote of both houses of the legislature. The governor has a great deal of power with respect to the state’s budget, probably far more than the President has with the federal budget. First of all, every year the governor requests or recommends to the legislature a specific level of funding for each agency and/or program in the state. As the budget works its way through the legislative labyrinth, the governor and his/her staff can try to influence the decisions of the legislators along the way. Eventually, when the specific appropriations bills emerge from the legislature, the Governor can either veto whole bills or specific line items from them.ii The governor is required to keep the state’s budget in balance, and to that end, the Constitution gives him/her the power to either temporarily or permanently withhold appropriated funds as the fiscal year runs its course. This means that an agency can not be guaranteed to receive what it was appropriated, especially if the state’s revenues are lower than expected. The governor is required by the constitution to carry out the laws, to keep the peace, and to annually give the legislature information on the state of the government. This obligation is typically met by the Governor’s annual address to the legislature, often referred to in the media as the “State of the State” speech, in which the governor sets out his or her priorities for the upcoming year, much as the president does in the annual State of the Union speech. It is also important to realize that much of the governor’s power is informal in nature, owing to the high visibility of the office. The governor can utilize the “bully pulpit” to help shape public opinion and thereby advance his or her agenda. The prestige of the office also enables the governor to cajole or persuade others and to negotiate attractive compromises between policy makers with different points of view. The governor’s prominence in his or her political party also provides some influence in working with the party’s leaders in the legislature, and that can help the governor accomplish his or her policy objectives. Several items in the state constitution that have to do with the governor were virtually copied from the U.S. constitution’s provisions concerning the president. For example, Missouri has a two-term limit for governor (and for the state’s treasurer) that reads very much like the 22nd Amendment term limit for president. In addition, there is a disability provision under which the governor can voluntarily (or involuntarily) temporarily turn over the responsibilities of the office to the lieutenant governor. The mechanisms of this process are very much like those in the 25th Amendment presidential disability procedures. Order of Succession to the Governorshipiii Lieutenant Governor President Pro Tem of the Senate Speaker of the House Secretary of State Auditor Treasurer Attorney General Lieutenant Governor The Missouri Constitution gives the lieutenant governor, as in most states, relatively few formal responsibilities. This person is designated by the state constitution as the “President of the Senate,” much as the vice-president of the United States is made the president of the U.S. Senate. This means that the lieutenant governor can preside over the senate, and in that capacity can do many of the things that a presiding officer would be expected to do, such as recognize members to speak, rule on points of order, etc. In addition, the lieutenant governor can cast a tie-breaking vote, as the U.S. vice-president can. But as in the case of the vice-president, the lieutenant governor has historically seldom been found actually presiding, except for ceremonial occasions or when the party leadership has expected a close vote for which the lieutenant governor might be asked to be present in order to break a tie. Some anecdotal evidence, however, seems to indicate that the lieutenant governor may be presiding more frequently now than in the past. One possible explanation may have to do with the implementation of term limits. A Lieutenant Governor may feel that presiding would allow him or her to contribute some experience and/or direction to a Senate whose members are likely to be less experienced than in the past. In addition, presiding over at least a portion of a day’s session means that the Lieutenant Governor’s name would be included in the Senate journal for that day, and therefore might provide some inoculation against a charge from political opponents that he or she was “not doing the job.” Rather than presiding over the Senate, lieutenant governors in the past have usually spent their time in a self-directed manner, working on matters of personal interest. Missouri statutes designate the lieutenant governor as a member of several commissions and advisory bodies, but those responsibilities are not terribly time demanding. In some cases, the governor may ask the lieutenant governor to work on certain special projects. However, since the governor and lieutenant governor are elected separately (and not as a team, as are the president and vice-president), those chosen by the voters may not actually function as a team. In fact, it is not uncommon for the governor and lieutenant governor to be from different parties. Of the six Governors elected since 1980, half have had a Lieutenant Governor of another party during at least part of their time in office. In such a scenario, it is unrealistic to expect the highest-ranking state official of one party to assign any significant responsibility to a potential competitor from another party, thereby helping increase that person’s political stature and reputation. Instead, the lieutenant governor in such situations usually has a great deal of free time to work on his or her own personal agenda. The lieutenant governor position is so short of genuine formal responsibilities that it was not until the 1970s when it even began to be considered a full-time job. In reality, the main responsibility of the lieutenant governor is to be available to step in in the case of the disability or death of the governor, as did Lieutenant Governor Roger Wilson when Governor Mel Carnahan died in a plane crash during the fall of 2000. Secretary of State Most people who are at all aware of the position of secretary of state are probably familiar with its responsibilities regarding elections, and in recent years, election reform. Though the secretary of state is the chief election official of Missouri, the position has other responsibilities, as well. The secretary of state is in charge of keeping the official documents and records of the state of Missouri. These items are maintained in a large, modern building just west of the Capitol, where the state archives and library may be visited and utilized by Missourians. Related to the responsibility of record keeping, the secretary of state also publishes the biennial Official Manual of the State of Missouri, informally known as “the Blue Book,” for its historically-blue covers. In the past, it was physically published and widely distributed across the state. Today, it is “published” online, and is available on the web page of the Secretary of State. The Official Manual is a source for a great deal of information about Missouri government, elected officials, state employees, etc. In the capacity of chief election official, the secretary of state provides information and training to local election officials, certifies statewide ballot issues and candidates for state office, and certifies the election results. In addition, the secretary of state may choose to lobby the state legislature for changes in the election laws. Auditor Though all of the other statewide executive officials are elected in presidential election years, the auditor is elected two years later in the mid-term elections. This relates to the responsibility of the auditor to verify that the expenditures of certain governmental offices and agencies were proper. From a practical matter, it would be impossible to audit the books of an outgoing administration if the auditor were leaving office at the same time. For several decades dating from the 1970s there was a string of certified public accountants chosen to be state auditor. Though this is not a formal constitutional qualification for the office, several candidates during that time found it both convenient and effective to campaign on their status as a CPA, and over time, being a CPA appeared to have become an informal qualification to be elected. Claire McCaskill, a non-CPA lawyer and former legislator and prosecutor from the Kansas City area, broke that string with her election in 1998. When she was elected to the US Senate in 2006, however, Missourians elected a CPA, Susan Montee, to be Auditor. She was challenged and defeated by a non-CPA, Thomas Schweich, in 2010. The constitution prohibits the legislature from assigning any non-financial responsibilities to the auditor,iv but auditors may voluntarily choose to expand their activities. For example, in recent years the auditor has also investigated how well state and local public agencies comply with the requirements of the state’s open records law. It remains to be seen whether the role of the auditor will expand further into non-financial investigations. Treasurer The treasurer is the only elected executive official other than the governor whose terms are limited. (Both are limited to two terms.) Conventional wisdom is that term limits were applied to the Treasurer position so that person would not develop too cozy a relationship with the billions of dollars of state money. Though there are several programs for which the treasurer is responsible (including the unclaimed property program and the MOST college tuition savings program), the main responsibility of the treasurer is to deposit the state’s receipts into various savings institutions, and then pay the bills and obligations of the state in a timely manner. The minimal policy discretion of this position has affected the nature of campaigns of those running for election to it. Most campaigns center on candidates’ qualifications and experience in state government or in dealing with large budgets. One unusual campaign during the 1980s revolved around the two major candidates’ different ideas over where the state’s money should be deposited, whether it should be in out-of-state banks that paid higher interest or in Missouri banks where the money might earn less interest, but would be available to Missouri customers for mortgages, business loans, etc. Attorney General The attorney general is the state’s chief lawyer. Interestingly, there is virtually nothing in the constitution about the position of attorney general, and very little in the state statutes. It is the attorney general’s responsibility to represent the state in court when, for example, a state law is being challenged. In addition to representing the state in court, the attorney general’s office provides legal advice to certain government officials. If an official or governmental body is contemplating taking a certain course of action but is in doubt about its legality or constitutionality, that person or entity can request an advisory opinion from the attorney general. The staff of the attorney general’s office researches the relevant statutory and case law, and issues a written opinion on the matter to provide direction in that case. The attorney general’s opinions are routinely published and made available to legal firms and law libraries, where lawyers can consult them for guidance in preparing their case.v i Agency personnel count provided in on-line version of Official Manual, State of Missouri, 2011-2012 edition, on web site of Secretary of State: http://www.sos.mo.gov ii The President has no such item veto power. During the 1990s, Congress passed a statute giving the president that power, but a subsequent Supreme Court decision declared that law unconstitutional, saying that an item veto would have to be established by constitutional amendment. iii Missouri Constitution, Article IV, Section 11(a). iv Article IV, Section 13. v A 1974 state Supreme Court case held, however, that the opinions of the attorney general are entitled to no more weight than that given the opinion of any other competent attorney. (Gershman Investment Corp. v. Danforth, 517 S.W. 2d 33)