STATUTE-OF-FRAUDS

advertisement

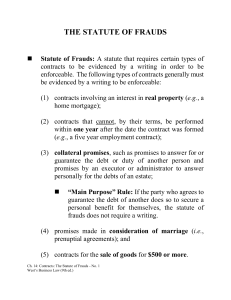

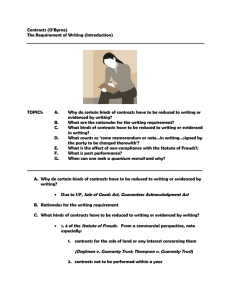

STATUTE OF FRAUDS CONTRACTS REQUIRED TO BE IN WRITING INTRODUCTION Every good book should have a chapter which begins—Once upon a time—so, this one will have one too: Once upon a in England, a party to a lawsuit was not permitted to testify in her own behalf. Also, any oral contract would be enforceable if its existence and terms were proven by the testimony of witnesses. This set of affairs encouraged the development of “professional” witnesses who would testify to about anything for a fee. Such perjured testimony would lead to judgments against innocent defendants for the breach of non—existent contracts. The English Parliament decided to remedy the problems of perjured testimony by enacting, in 1677, “An Act for the Prevention of Frauds and Perjuries”——or, as it is commonly known, the “Statute of Frauds”. As enacted, the Statute of Frauds provided that no suit be brought upon certain types of contracts unless the contract were in writing and signed by the party to be charged——the party being sued. Section 4 of the Statute required the following types of contracts to be in writing: 1. Contracts for the sale of land or an interest therein. 2. Contracts that are impossible to perform within one year. 3. A promise made by one person to pay the debt of another 4. A promise made by an executor or an administrator of an estate to pay a debt of the estate out of her own funds. 5. A promise made in consideration of marriage. Section 17 of the Statute required that contracts for the sale of goods at a price of ten pounds or more (probably a considerable sum in 1677) be in writing unless: (1) the buyer paid part of the purchase price; or (2) the seller delivered and the buyer accepted part of the goods. In the United States today, every state has enacted its own Statute of Frauds with writing requirements similar to those contained in Section 4 of the English Act (which has 1 since been abolished in England, by the way). The writing requirements with regard to the sale of goods is presently controlled in the United States by Section 2—201 of the UCC which has some similarities to Section 17 of the original Act and applies to the sale of good costing $500.00 or more. Since our current legal system has different rules than that of England in 1677, e.g., parties to a lawsuit can testify in their own behalf, the Statute of Frauds continues as part of our system not out of a need to prevent perjured testimony but out of a traditional belief that certain contracts ought to be in writing. This chapter will explore those contracts that are required to be in writing (The fact that only certain contracts, rather than all contracts, need to be in writing to be enforceable usually comes as a surprise to many students.). I use a somewhat different classification system than most other authors when discussing the Statute of Frauds. In order to assist you in learning this material, I have classified the various Statute of Frauds provisions into categories that I hope will be easier to remember than the individual provision: A. Contracts people are prone to forget. In this category are contracts that cannot be completed in one year. B. Contracts that go against the common sense of our culture. Included in this category promises made in consideration of marriage, promises to pay the debt of another, and promises of an executor or administrator to pay a debt out of her own funds. C. Contracts involving important matters. Here I include contracts for the sale of land or an interest therein contracts for the sale of goods over $500.00. (Note: To avoid confusion of the material on the Statute of Frauds with the material on fraud, it is advisable that you think of the Statute of Frauds as the Statute of Writings.) CONTRACTS PEOPLE ARE PRONE TO FORGET Contracts which by their terms are impossible to complete within one year from the making thereof must be in writing and signed by the party to be charged. Case 1A: Ill Advized entered into an oral contract whereby he agreed to work as a salesman for Schlok Company for two years. After working for six 2 months, Schlok fired Ill without cause and Ill brought suit for breach of the employment contract. If Schlok defends on the basis that the contract must be in writing under the Statute of Frauds, Ill will lose. Note: Even though the contract is not enforceable, Ill will be able to recover in quasi—contract for the time he actually worked for Schlok Case 1B: Assume the same facts except that Ill, on March 15th, entered into a contract of employment for one year to begin on April lst. This contract is also unenforceable because even though the period of employment is one year, it will take over a year from the making of the contract (March 15th) to complete the performance. Case 1C: Assume the same facts as case IA except that the term of employment is “for Ill’s life”. This oral contract is enforceable because Ill could possibly die during the first year, therefore, the contract is possible to complete within one year. (Younger students often have a difficult time with this example; older students, more aware of their own mortality, seem to catch on more quickly.) The Statute of Frauds is a “technical” defense to enforcement of a contract that is proper in all respects except that it is not in writing and/or not signed by the party being sued. The nature of this defense often results in refusal of a court to enforce an oral contract that has been proven or even admitted. Since such apparently unjust results are possible through the application of the defense of Statute of Frauds, its use to get out of contracts is disfavored by the courts. Of all the provisions within the Statute of Frauds, “contract which can not be completed in one year” is perhaps the most disfavored. This lack of favor has led courts to adopt a very restricted application of this provision. If there is even the slightest possibility that contract may be performed within one year, it does not have be in writing to be enforceable. Case 2A: Frank Lloyd Wrong, an architect, is hired under an oral contract to draw the plans for and supervised the construction of a new hospital It is anticipated that the project will take about three years to complete. Frank’s term of employment is “the time required to complete the hospital.” It is likely that this oral contract will be held enforceable despite the expected three-year completion time. This is because the hospital could be completed within one year if, say, they hired an extra 10,000 people to work on it. 3 Case 2B: Given the same facts as above except the term of the contract is “five years” and the contract provides that it can be terminated at any time after the plans are drawn by mutual agreement. This oral contract is unquestionably enforceable because there is a possibility that the termination clause could be exercised within one year. There is an exception to this provision of the Statue of Frauds: oral contracts which are wholly executed by one party within a year are enforceable even though the other party’s performance will extend beyond the year. Typical of this exception are loan agreements that are to be repaid over a period in excess of one year. Here, the creditors performance is fully executed by the loan of the money and only the debtor s performance is to extend beyond the year period. Such an oral loan would be enforceable. In addition to this exception, some courts refuse to hold or-al contracts in excess of one year unenforceable on the basis of equitable estoppel. For example, where one party goes to a great deal of expense in beginning the performance of such an oral contract, say, by moving to a new town and purchasing a home in order to commence performance on a two year employment contract, some courts would hold that the other party (the employer) would be equitably estopped from relying on the Statute of Frauds as a defense to a breach of contract suit. CONTRACTS THAT GO AGAINST THE COMMON SENSE OF OUR CULTURE INTRODUCTION In this category I have included those Statute of Frauds provisions that relate to agreements which in my opinion go against the common sense of our culture in the United States. For example, we believe, for better of worse, that people get married because of mutual love and affection, therefore, an agreement that has some other consideration than a mutual promise to marry, goes against our cultural norms. If you dislike paying your bills as much as I do, you will understand my position that agreements to pay the debt of another are against our common sense. Also covered in this category are agreements of an executor or administrator to pay the debts of the estate out of her own funds. I believe that this last 4 Statute of Frauds provision is really a more specific example of the general provision regarding agreements to pay the debt of another, therefore, I will not treat it separately below. CONTRACTS IN CONSIDERATION OF MARRIAGE Contracts in consideration of marriage must be in writing and signed by the party to be charged to be enforceable. The one exception is mutual promises to marry. Therefore, the old Simon Lagree lines “If you marry me, I’ll tear up the mortgage on your Mother’s home” would not be enforceable unless Simon put it in a signed writing. Prenuptial agreements, a type of contract where people who are contemplating marriage agree to the distribution of assets and liabilities during the marriage and in the event of a subsequent divorce, are becoming much more common these days. One you may have heard of is the prenuptial agreement between Aristotle Onasis and Jacqueline Bouviere Kennedy. These agreements have become familiar fare at “adult” communities where older folks are getting married late in life and want to protect their respective childrens’ and grandchildrens’ rights to the assets that they have accumulated over the years. Additionally, many people who have been through the financial “horrors” of a divorce, make prenuptial agreements prior to second marriages. PROMISES TO PAY THE DEBT OF ANOTHER If there is an debtor—creditor relationship and a third party promises the creditor: “If your debtor doesn’t pay, I’ll pay”, then the third party’s promise must be in writing and signed by her to be enforceable. The usual form of this type of agreement is a promise of one party to be a surety or guarantor regarding the debt of a principle debtor. In order f or a writing to be required: (1) the promise must be secondary—there must be someone else to whom the creditor is first required to look to for payment; and (2) the promise must be made to the creditor not to the original debtor. Note: An arrangement where one party agrees to cosign with another does not fall within 5 this category because the creditor is not required to look to either party first for Case 3A: Speedo Spoke and his friend Shiela Surety went to a Yamahonda motorcycle dealer because Speedo was interested in purchasing a new “bike”. Speedo decided upon a 750cc model that cost $1,500.00. During a discussion of the purchase with the dealer, it became obvious that Speedo did not have adequate credit but Sheila’s credit was fine. Shiela told the dealer: “If you sell the bike to Speedo and he fails to pay, I’ll pay.” On the basis of Shiela’s oral promise, the dealer sold the bike to Speedo on an installment contract. Speedo failed to pay, and the dealer brought a suit against Shiela to enforce her promise to guarantee Speedo’s payment. If Shiela defends on the basis of the Statute of Frauds, she will win because her promise made to the creditor (the dealer) to pay the debt of the debtor (Speedo) in the event of the debtor’s failure to pay must be in writing and signed by Shiela to be enforceable. Case 3B: Assume the same facts as above except that Shiela says to the dealer: “If you sell the bike to Speedo, I’ll pay for it.” Shiela’s oral promise is enforceable because she is promising to be primarily liable rather than secondarily liable—she has made an unconditional promise to pay for the bike. Case 3C: Assume the same facts as in Case 3A except that: (1) the dealer is willing to sell to Speedo; (2) Speedo doubts whether he can pay for the bike; and (3) Shiela says to Speedo: “If you buy the bike and can’t pay, I’ll pay.” This oral promise is enforceable because it is made to the debtor (Speedo) rather than the creditor (the dealer). Note: In this case Speedo would enforce Shiela’s promise because the dealer is not a party to the agreement. There is an exception to this provision of the Statute of Frauds that is known as the “main purpose” or “leading object” rule. This exception applies where the person who makes an oral promise to be secondarily liable for the debt of another has as an objective or main purpose obtaining a personal benefit for herself. Under such circumstances, a court will treat the oral promise of secondary liability as if it were a promise to be primarily liable and will enforce the promise. Case 4: Assume the same facts as in Case 3A except that when the dealer sues Shiela he proves that Shiela rather than Speedo has been using the bike for six months since the purchase. Under such circumstances, it is quite likely that the court would enforce Shiela’s oral promise by applying the “leading object” or “main purpose” rule. 6 This exception is often applied in cases involving closed corporations where the majority stockholder makes an oral promise to pay the debt of the corporation should the corporation fail to pay. Courts generally treat such promises as coming within the exception because of the virtual identity between the corporation and its major stockholder. CONTRACTS INVOLVING IMPORTANT MATTERS INTRODUCTION Our legal system was brought with the Pilgrims from England. When the English legal system was developing, the English economy was based on land rather than goods. Even in our modern legal system, land is regarded as a matter of great import, therefore, I have included the Statute of Frauds provision regarding “the sale of land or an interest therein” in this category. The drafters of the U.C.C have set $500.00 as the amount where sales of goods obtain significant import for a writing to be required, therefore, the Statute of Frauds section of the U.C.C. (2—201) will be discussed in this category. CONTRACTS FOR THE SALE OF LAND OR AN INTEREST THEREIN Contracts for the sale of land or an interest therein must be in writing and signed by the party to be charged in order to be enforceable. Interests in land include mortgages, easements, leases of mineral rights, and in many states, real estate brokers’ contracts. An exception to this writing requirement is known as the “Part Performance Doctrine”. Under this exception, if a purchaser under an oral contract for the sale of land has begun performance in such a way that her conduct unequivocally proves the existence and terms of the oral contract, then the oral contract will be enforceable. For the part performance doctrine to apply there must be a combination of the following three items: (1) possession; (2) part or full payment; and (3) improvements. The doctrine will not apply if there has only been possession or payment. For it to apply there must be a combination of possession and part or full payment, possession and improvements, or possession and both. 7 The basis of this exception is that people would not behave in this manner—pay money, take possession of property, and make improvements on the property—unless there were a contract of sale. Case 5A: Notso Bright orally agrees to purchase Sly Fox’s property. Notso pays Sly the purchase price of $65,000.00, takes possession of the property, and rebuilds the barn. Sly later sues Notso for the return of the land claiming that the oral contract is unenforceable. As Notso has taken possession, paid the full purchase price, and made extensive improvements, the facts unequivocally prove the existence of a contract for the sale of the land for $5,000.000. The oral contract will be enforceable under the part performance doctrine. Case 5B: Assume that Notso purchased the farm on a land contract that provided for no money down and a monthly payment of $350.00 per month. This oral contract might still be enforceable on the basis of the combination of part payment, possession, and extensive improvements. Case 5C: Assume that Notso purchased on the land contract, that he did not rebuild the barn, and that Sly claims that the agreement was a month to month rental rather than a contract of sale. This oral contract will not be enforceable because the facts do not unequivocally prove a contract of sale—a rental arrangement is entirely consistent with these facts CONTRACTS FOR THE SALE OF GOODS COSTING $500.00 OR MORE The Statute of Frauds provision of the UCC regarding the sale of goods is Section 2—201. What follows summarizes the contents of Section 2—201 and assumes that you are familiar with the exact wording of the Code Section, therefore, you are advised to turn to the Appendix of your book and examine the wording of Section 2—201 before continuing to read this text. Under Section 2—201(1), to be enforceable a contract for the sale of goods for $500.00 or more must be evidenced by some writing sufficient to indicate a contract has been made and the writing must be signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought. This writing need not be formal, and is not insufficient because it omits or incorrectly states a term; however, such a writing is not, enforceable beyond the quantity of 8 goods shown in the writing. The exceptions to this rule are found in Subsections 2—201 (2), 2—201(3) (a), (3)(b), and (3)(c). These exceptions can be listed as follows: 1. The “Merchant” exception [2—201 (2)] Where one merchant sends another merchant a written confirmation of an c contract and the merchant receiving the confirmation does not object to it within ten days of receiving the confirmation the contract is enforceable. 2. The “Specially Manufactured Goods” exception [2—201 (3)(a)]. Where: (a) goods are to be specially manufactured for buyer under an oral contract; and (b) before a repudiation is received, the seller has made a substantial beginning of the manufacture or has made commitments for their procurement; and (c) the goods are not suitable for sale to others in ordinary course of the seller’s business—then the contract is enforceable. 3. The “Admission” exception [2-201 (3)(c)]. Where the party against whom enforcement is sought admits in his pleadings, testimony, or otherwise in court that a contract was made, the contract is enforceable. The admitted contract is enforceable; however, it is only to the extent of the goods admitted. 4. The “Goods Received and Accepted” exception [2-201 (3)(c)]. Where the buyer under an oral contract receives and accepts goods, the contract is enforceable. 5. The “Payment” exception [2-201(3)(c)]. Where payment has been made by the buyer and accepted by the seller under an oral contract, the contract is enforceable. Note: With part payment there are two possible outcomes: (1) if part payment is made on an indivisible item, say, an automobile, then the entire contract is enforceable because the part payment ii directly related to the whole car; (2) if the part payment is on a contract involving divisible items, say, bushels of wheat, then the contract is enforceable only to the extent of the number of bushels covered by the part payment. NATURE OF THE WRITING REQUIRED The writing required satisfy the Statute of Fraud need not be formal and need not be contained in one document. For the non-U.CC. Statute of Frauds provisions all that is necessary is that the writing describe the identity of the parties, the subject matter, and with reasonable certainty all other material terms. Under the UCC, the writing requirement is even more relaxed. Under the UCC, a writing may be sufficient even where terms are omitted or incorrectly stated. 2-201(1). The writing could be a letter or series of letters that the parties do not believe to be of legal significance A satisfactory memorandum could consist of several documents, none of 9 which would be sufficient by itself. The required writing could even be a letter repudiating the oral agreement. The one certain requirement is that the signature (or other identifying mark) of the party against whom enforcement is sought be present at some place that indicates an acknowledgement of the existence of a contract and its terms. EFFECT OF FAILURE TO COMPLY WITH THE STATUTE OF FRAUDS Failure to comply with the Statute of Frauds does not make a contract void, it merely gives the party against whom enforcement is sought a defense to a suit brought to enforce the contract or sue for its breach. This means that the contract will be enforced if the defendant fails to raise the Statute of Frauds as a defense; however, if any attorney should fail to raise this defense, she had better have her malpractice insurance paid up. 10