America & The Progressive Movement: Late 19th Century/ Early 20th Century

The Industrial Revolution, which took place from the 18th to 19th centuries, was a period during which

predominantly agrarian, rural societies in Europe and America became industrial and urban. Prior to the

Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain in the late 1700s, manufacturing was often done in

people’s homes, using hand tools or basic machines. Industrialization marked a shift to powered,

special-purpose machinery, factories and mass production. The iron and textile industries, along with

the development of the steam engine, played central roles in the Industrial Revolution, which also saw

improved systems of transportation, communication and banking. While industrialization brought about

an increased volume and variety of manufactured goods and an improved standard of living for some, it

also resulted in often grim employment and living conditions for the poor and working classes.

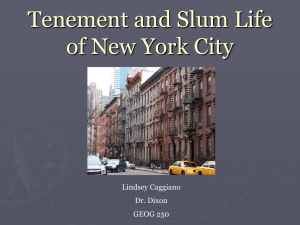

In the 19th century, more and more people began crowding into America's cities, including thousands of

newly arrived immigrants seeking a better life than the one they had left behind. In New York City-where the population doubled every decade from 1800 to 1880--buildings that had once been singlefamily dwellings were increasingly divided into multiple living spaces to accommodate this growing

population. Known as tenements, these narrow, low-rise apartment buildings--many of them

concentrated in the city's Lower East Side neighborhood--were all too often cramped, poorly lit and

lacked indoor plumbing and proper ventilation. By 1900, some 2.3 million people (a full two-thirds of

New York City's population) were living in tenement housing.

The Rise of Tenement Housing

In the first half of the 19th century, many of the more affluent residents of New York's Lower East Side neighborhood

began to move further north, leaving their low-rise masonry row houses behind. At the same time, more and more

immigrants began to flow into the city, many of them fleeing famine in Ireland or revolution in Germany. Both of these

groups of new arrivals concentrated themselves on the Lower East Side, moving into row houses that had been

converted from single-family dwellings into multiple-apartment tenements, or into new tenement housing built

specifically for that purpose.

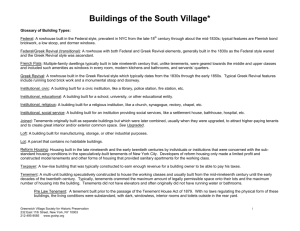

A typical tenement building had five to seven stories and occupied nearly all of the lot upon which it was built (usually

25 feet wide and 100 feet long, according to existing city regulations). Many tenements began as single-family

dwellings, and many older structures were converted into tenements by adding floors on top or by building more

space in rear-yard areas. With less than a foot of space between buildings, little air and light could get in. In many

tenements, only the rooms on the street got any light, and the interior rooms had no ventilation (unless air shafts were

built directly into the room). Later, speculators began building new tenements, often using cheap materials and

construction shortcuts. Even new, this kind of housing was at best uncomfortable and at worst highly unsafe.

Calls for Reform

New York was not the only city in America where tenement housing emerged as a way to accommodate a growing

population during the 1900s. In Chicago, for example, the Great Fire of 1871 led to restrictions on building wood-

frame structures in the center of the city and encouraged the construction of lower-income dwellings on the city's

outskirts. Unlike in New York, where tenements were highly concentrated in the poorest neighborhoods of the city, in

Chicago they tended to cluster around centers of employment, such as stockyards and slaughterhouses.

Nowhere, however, did the tenement situation become as dire as it was in New York, particularly on the Lower East

Side. A cholera epidemic in 1849 took some 5,000 lives, many of them poor people living in overcrowded housing.

During the infamous "draft riots" that tore apart the city in 1863, rioters were not only protesting against the new

military conscription policy; they were also reacting to the intolerable conditions in which many of them were living.

The Tenement House Act of 1867 legally defined a tenement for the first time and set construction regulations;

among these were the requirement of one toilet (or privy) per 20 people.

"How the Other Half Lives"

The existence of tenement legislation did not guarantee its enforcement, however, and conditions were little improved

by 1889, when the Danish-born author and photographer Jacob Riis was researching the series of newspaper articles

that would become his seminal book "How the Other Half Lives." Riis had experienced firsthand the hardship of

immigrant life in New York City, and as a police reporter for newspapers, including The Evening Sun, he had gotten a

unique view into the grimy, crime-infested world of the Lower East Side. Seeking to draw attention to the horrible

conditions in which many urban Americans were living, Riis photographed what he saw in the tenements and used

these vivid photos to accompany the text of "How the Other Half Lives," published in 1890.

The hard facts included in Riis' book--such as the fact that 12 adults slept in a room some 13 feet across, and that the

infant death rate in the tenements was as high as 1 in 10--stunned many in America and around the world and led to

a renewed call for reform. Two major studies of tenements were completed in the 1890s, and in 1901 city officials

passed the Tenement House Law, which effectively outlawed the construction of new tenements on 25-foot lots and

mandated improved sanitary conditions, fire escapes and access to light. Under the new law--which in contrast to

past legislation would actually be enforced--pre-existing tenement structures were updated, and more than 200,000

new apartments were built over the next 15 years, supervised by city authorities.

Life After the Tenements

By the late 1920s, many tenements in Chicago had been demolished and replaced with large, privately subsidized

apartment projects. The next decade saw the implementation of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, which

would transform low-income housing in many American cities through programs including slum clearing and the

building of public housing. The first fully government-built public housing project opened in New York City in 1936.

Called First Houses, it consisted of a number of rehabilitated pre-law tenements covering a partial block at Avenue A

and East 3rd Street, an area that had been considered part of the Lower East Side.

Among the trendy restaurants, boutique hotels, and bars that can be found in the neighborhood today, visitors can

still get a glimpse into its past at the Lower East Side Tenement Museum, located at 97 Orchard Street. Built in 1863,

the building is an example of an "old-law" tenement (as defined by the Tenement House Act of 1867) and was home

over the years for some 7,000 working class immigrants. Though the basement and the first floor have been

renovated, the rest of the building looks much the same as it did in the 19th century, and has been designated a

National Historic Site.

Child Labor in America

Although children had been servants and apprentices throughout most of human history, child labor

reached new extremes during the Industrial Revolution. Children often worked long hours in dangerous

factory conditions for very little money. Children were useful as laborers because their size allowed

them to move in small spaces in factories or mines where adults couldn't fit, children were easier to

manage and control and perhaps most importantly, children could be paid less than adults. Child

laborers often worked to help support their families, but were forced to forgo an education. Nineteenth

century reformers and labor organizers sought to restrict child labor and improve working conditions,

but it took a market crash to finally sway public opinion. During the Great Depression, Americans

wanted all available jobs to go to adults rather than children.

The minimal role of child labor in the United States today is one of the more remarkable changes in the social and

economic life of the nation over the last two centuries. In colonial America, child labor was not a subject of

controversy. It was an integral part of the agricultural and handicraft economy. Children not only worked on the family

farm but were often hired out to other farmers. Boys customarily began their apprenticeship in a trade between ages

ten and fourteen. Both types of child labor declined in the early nineteenth century, but factory employment provided

a new opportunity for children. Ultimately, young women and adult immigrants replaced these children in the textile

industry, but child labor continued in other businesses. They could be paid lower wages, were more tractable and

easily managed than adults, and were very difficult for unions to organize.

The educational reformers of the mid-nineteenth century convinced many among the native-born population that

primary school education was a necessity for both personal fulfillment and the advancement of the nation. This led

several states to establish a minimum wage for labor and minimal requirements for school attendance. These laws

had many loopholes, however, and were in place in only some states where they were laxly enforced. In addition, the

influx of immigrants, beginning with the Irish in the 1840s and continuing after 1880 with groups from southern and

eastern Europe, provided a new pool of child workers. Many of these immigrants came from a rural background, and

they had much the same attitude toward child labor as Americans had in the eighteenth century.

The new supply of child workers was matched by a tremendous expansion of American industry in the last quarter of

the nineteenth century that increased the jobs suitable for children. The two factors led to a rise in the percentage of

children ten to fifteen years of age who were gainfully employed. Although the official figure of 1.75 million

significantly understates the true number, it indicates that at least 18 percent of these children were employed in

1900. In southern cotton mills, 25 percent of the employees were below the age of fifteen, with half of these children

below age twelve. In addition, the horrendous conditions of work for many child laborers brought the issue to public

attention.

Determined efforts to regulate or eliminate child labor have been a feature of social reform in the United States since

1900. The leaders in this effort were the National Child Labor Committee, organized in 1904, and the many state child

labor committees. These organizations, gradualist in philosophy and thus prepared to accept what was achievable

even if not theoretically sufficient, employed flexible tactics and were able to withstand the frustration of defeats and

slow progress. The committees pioneered the techniques of mass political action, including investigations by experts,

the widespread use of photography to dramatize the poor conditions of children at work, pamphlets, leaflets, and

mass mailings to reach the public, and sophisticated lobbying. Despite these activities, success depended heavily on

the political climate in the nation as well as developments that reduced the need or desirability of child labor.

During the period from 1902 to 1915, child labor committees emphasized reform through state legislatures. Many

laws restricting child labor were passed as part of the progressive reform movement of this period. But the gaps that

remained, particularly in the southern states, led to a decision to work for a federal child labor law. Congress passed

such laws in 1916 and 1918, but the Supreme Court declared them unconstitutional.

The opponents of child labor then sought a constitutional amendment authorizing federal child labor legislation.

Congress passed such an amendment in 1924, but the conservative political climate of the 1920s, together with

opposition from some church groups and farm organizations that feared a possible increase of federal power in areas

related to children, prevented many states from ratifying it.

The Great Depression changed political attitudes in the United States significantly, and child labor reform benefited.

Almost all of the codes developed under the National Industrial Recovery Act served to reduce child labor. The Fair

Labor Standards Act of 1938, which for the first time set national minimum wage and maximum hour standards for

workers in interstate commerce, also placed limitations on child labor. In effect, the employment of children under

sixteen years of age was prohibited in manufacturing and mining.

This success arose not only from popular hostility to child labor, generated in no small measure by the long-term work

of the child labor committees and the climate of reform in the New Deal period, but also from the desire of Americans

in a period of high unemployment to open jobs held by children to adults.

Other factors also contributed in a major way to the decline of child labor. New types of machinery cut into the use of

children in two ways. Many simple tasks done by children were mechanized, and semiskilled adults became

necessary for the most efficient use of the equipment. In addition, jobs of all sorts increasingly required higher

educational levels. The states responded by increasing the number of years of schooling required, lengthening the

school year, and enforcing truancy laws more effectively. The need for education was so clear that Congress in 1949

amended the child labor law to include businesses not covered in 1938, principally commercial agriculture,

transportation, communications, and public utilities.

Although child labor has been substantially eliminated, it still poses a problem in a few areas of the economy.

Violations of the child labor laws continue among economically impoverished migrant agricultural workers. Employers

in the garment industry in New York City have turned to the children of illegal immigrants in an effort to compete with

imports from low-wage nations. The recent liberalization of the federal government's rules concerning work done at

home also increases the likelihood of illegal child labor. Finally, despite the existing laws limiting the number of hours

of work for those still attending school, some children continue to labor an excessive number of hours or hold

prohibited jobs. Effectiveness in enforcement varies from state to state. Clearly, the United States has not yet

eliminated all the abuses and violations, but it has met the objective of the child labor reformers and determined by

law and general practice that children shall not be full-time workers.

Citations:

Walter Trattner, Crusade for the Children: A History of the National Child Labor Committee and Child Labor Reform in

America (1970).

IRWIN YELLOWITZ

The Reader's Companion to American History. Eric Foner and John A. Garraty, Editors. Copyright © 1991 by

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

42b. Muckrakers

Upton Sinclair published The Jungle in 1905 to expose labor abuses in the meat packing industry. But it was food,

not labor, that most concerned the public. Sinclair's horrific descriptions of the industry led to the passage of the

Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act, not to labor legislation.

The pen is sometimes mightier than the sword.

It may be a cliché, but it was all too true for journalists at the turn of the century. The print revolution

enabled publications to increase their subscriptions dramatically. What appeared in print was now

more powerful than ever. Writing to Congress in hopes of correcting abuses was slow and often

produced zero results. Publishing a series of articles had a much more immediate impact. Collectively

called MUCKRAKERS, a brave cadre of reporters exposed injustices so grave they made the blood of the

average American run cold.

Steffens Takes on Corruption

The first to strike was LINCOLN STEFFENS. In 1902, he published an article inMCCLURE'S magazine

called "TWEED DAYS IN ST. LOUIS." Steffens exposed how city officials worked in league with big

business to maintain power while corrupting the public treasury.

More and more articles followed, and soon Steffens published the collection as a book entitled THE

SHAME OF THE CITIES. Soon public outcry demanded reform of city government and gave strength to

the progressive ideas of a city commission or city manager system.

Tarbell vs. Standard Oil

IDA TARBELL struck next. One month after Lincoln Steffens launched his assault on urban politics,

Tarbell began her McClure's series entitled "HISTORY OF THE STANDARD OIL COMPANY." She outlined

and documented the cutthroat business practices behind John Rockefeller's meteoric rise. Tarbell's

motives may also have been personal: her own father had been driven out of business by Rockefeller.

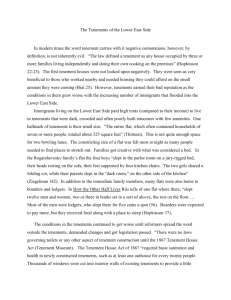

John Spargo's 1906 The Bitter Cry of the Children exposed hardships suffered by child laborers, such as these coal

miners. "From the cramped position [the boys] have to assume," wrote Spargo, "most of them become more or

less deformed and bent-backed like old men ... "

Once other publications saw how profitable these exposés had been, they courted muckrakers of their

own. In 1905, THOMAS LAWSON brought the inner workings of the stock market to light in FRENZIED

FINANCE. JOHN SPARGO unearthed the horrors of child labor in THE BITTER CRY OF THE CHILDREN in

1906. That same year, DAVID PHILLIPS linked 75 senators to big business interests in THE TREASON OF

THE SENATE. In 1907, WILLIAM HARDwent public with industrial accidents in the steel industry in the

blistering MAKING STEEL AND KILLING MEN. RAY STANNARD BAKER revealed the oppression of Southern

blacks in FOLLOWING THE COLOR LINE in 1908.

The Meatpacking Jungle

Perhaps no muckraker caused as great a stir as UPTON SINCLAIR. An avowed Socialist, Sinclair hoped

to illustrate the horrible effects of capitalism on workers in the Chicago meatpacking industry. His

bone-chilling account, THE JUNGLE, detailed workers sacrificing their fingers and nails by working with

acid, losing limbs, catching diseases, and toiling long hours in cold, cramped conditions. He hoped the

public outcry would be so fierce that reforms would soon follow.

Yale University

This sketch of "Gotham Court" from Jacob Riis's How the Other Half Lives shows the bitter side of tenement life.

The clamor that rang throughout America was not, however, a response to the workers' plight. Sinclair

also uncovered the contents of the products being sold to the general public. Spoiled meat was

covered with chemicals to hide the smell. Skin, hair, stomach, ears, and nose were ground up and

packaged as head cheese. Rats climbed over warehouse meat, leaving piles of excrement behind.

Sinclair said that he aimed for America's heart and instead hit its stomach. Even President Roosevelt,

who coined the derisive term "muckraker," was propelled to act. Within months, Congress passed

the PURE FOOD AND DRUG ACT and the MEAT INSPECTION ACT to curb these sickening abuses.