Decades later, bitter memories of Chavez Ravine The Dodgers

advertisement

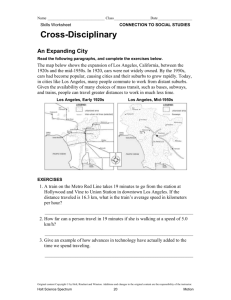

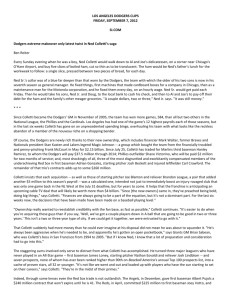

Decades later, bitter memories of Chavez Ravine The Dodgers prepare to mark the 50th anniversary of the stadium in Chavez Ravine. For the neighbors who were uprooted from the site, it's a somber milestone. By Hector Becerra, Los Angeles Times April 5, 2012 Lou Santillan was a teenager when his parents were forced out of their home in Chavez Ravine, the hillside area overlooking downtown Los Angeles that would eventually become the home of Dodger Stadium. The family's love for the old neighborhood was so strong that Santillan's father wrote a Mexican ballad about it. Lou organized an annual reunion of the other families who were uprooted before the bulldozers moved in to clear their little community. And like many of his generation, the 77year-old had no love for the Dodgers. In spite of that family history, Santillan's son Eddie, 46, has been a Dodgers fan since childhood. He grew up cheering for Ron Cey, Steve Garvey and, of course, Fernando Valenzuela. And as a parking attendant for 27 years at City Hall, he's gotten his picture taken with the O'Malleys, Tom Lasorda and even Frank McCourt. "There's people who won't even step into Dodger Stadium. They're still bitter. My uncle, who was a priest, he wouldn't have gone to any Dodger games," Eddie said. "But I had no anger or frustration against them. I love the Dodgers. Growing up in L.A., that's our team, you know." Eddie Santillan, like many other fans, was jubilant last week when McCourt sold the Dodgers to a group including former Lakers star Magic Johnson. The sale came on the eve of a new season and the 50th anniversary of the opening of Dodger Stadium in 1962. The milestone will be marked by tributes and remembrances. But for families like the Santillans — who call themselves "los desterrados" ("the uprooted") — the anniversary will be more somber and complicated. The Dodgers' move to Los Angeles in 1958 — playing their first several years at the Coliseum — was a seminal event, heralding what many saw as the city's arrival in the big leagues of world metropolises. But the removal of more than 1,000 mostly Mexican American families from Chavez Ravine to make way for the stadium is a dark note in L.A.'s history. The last family was dragged away kicking and screaming and weeping, and the removals became a rallying symbol of Latino L.A. history and activism. Many of the people evicted are long dead, but there are still more than a few aging witnesses to the episode. On a recent afternoon, Eddie pushed his father's wheelchair outside of an Alhambra nursing home. Lou suffered a stroke about five years ago, and Eddie and his brother gladly stepped in to help their dad continue to organize the yearly picnic for survivors from the ravine. But although more than a few of the participants wouldn't be caught dead in Dodger Stadium, and reveled in the team's struggles, Eddie's compact did not mean abandoning his team or regular trips to the stadium. "You know I like the Dodgers, right, Pop?" he asked his father. "That's you," Lou replied with exaggerated curtness. "It's still America." Then with a mischievous glint in his eye, he added: "Hey, send the Occupy people to Dodger Stadium!" A close community Before the homes were cleared, Chavez Ravine was a rural village overlooking downtown L.A. It was a place of ramshackle homes, dusty unpaved roads, roaming goats, sheep and cattle, and a largely Mexican American population. People like Santillan remember a life of few luxuries but a sense of community and adventure, with sprawling Elysian Park as a backyard playground. "When there was a party in the neighborhood, nobody called the police that you were making a lot of noise because everybody was at the party," recalled Albert Elias, 80, of Bellflower. In the early 1950s, the city used eminent domain to begin moving everyone out to make room for a federally funded public housing project. Most families received several thousand dollars, though the amounts varied. Most of the families were moved out in the early '50s, with promises that they could be resettled into those new housing units. Al Zepeda, 74, remembers the exact day his family left the neighborhood: Jan. 28, 1952. He turned 14 that day — his birthday party becoming a moving party. "I celebrated by moving boxes, moving furniture and pulling our refrigerator up some stairs," Zepeda said with a laugh. "That was my party." But the public housing effort came during the McCarthy "Red scare" era, and critics condemned public housing as being part of a "socialist plot." The housing plan was eventually abandoned, but by then most of the neighborhood was cleared. By 1957, Brooklyn Dodgers owner Walter O'Malley was already thinking of moving the team west. Flying over L.A. one day, O'Malley asked about the site. The next year, the city agreed to a deal for the land with O'Malley. A year later, only a few holdouts remained in the neighborhood. On May 9, 1959, the city moved to evict the group. TV cameras captured one particularly ugly confrontation in which sheriff's deputies dragged the Arechiga family from the property. Dramatic scenes The matriarch of the family, Abrana, cursed at them. Her daughter, kicking and screaming as she was carried away, was arrested and charged with battery. "I was there when they went down," Zepeda said. "Louie [Santillan] was there too. We were there when the bulldozers went in. They were trying to get the dog out of the way so it wouldn't be trampled by the tractor." The patriarch of the family, Manuel Arechiga, set up a tent and refused to budge even after the bulldozers knocked down their house. The land was eventually cleared of houses and people. Few people in the city did as much to get the Dodgers to L.A., and then to their new home in Chavez Ravine, as Roz Wyman. She was 22 when she became a councilwoman in 1953. She has been credited with successfully pushing to relocate the Dodgers from Brooklyn. Now 81, Wyman is an unabashed Dodgers fan, having counted Walter O'Malley and many a Dodgers blueblood as friends. It always bothered her, she said, that some people thought the Dodgers kicked those people out. "The Dodgers had absolutely nothing to do with that land being cleared. Nothing to do with it," she said. "The thing was, the land was not productive after the people took their money and moved. No taxes were coming out of it, no revenue, no nothing." During the last of the Chavez Ravine evictions, the city hired private security for Wyman after she received some threats. Wyman said the anger at her faded, but she knows the bitterness of those evicted remains. She said she has no regrets. "It was the first time in Los Angeles that this town pulled together for something," Wyman said. "The Dodgers brought the city together." Lingering emotions For the ravine refugees, however, Dodger Stadium broke their community apart. When the ballpark opened, some threw tomatoes into the parking lot. Many of the people who were evicted are now in their 70s and 80s, and they describe the sadness not only of being separated from friends but of seeing their parents unmoored after having to move away. Melissa Arechiga, 36, said she recalled her grandfather's distrust of anyone in government in the wake of the battle, from the tax collector to the parking enforcer. Did he hate the Dodgers? Until he died last year, "Grandpa John" was inscrutable. He never went to a game, as far as Arechiga knows. But she said she remembers her granddad listening to Dodgers games, and she thinks "Fernandomania" must have been "bittersweet" for him either way. Arechiga said that early on, she couldn't relate to some of her family members' abiding anger. She joined a street gang and, like many gang members, adopted the Dodgers' iconic interlocking "L.A." symbol. "It was not because I was a genuine Dodger fan," she said. "It was more for gang identification. It's kind of ironic." Now an undergraduate at UC Berkeley, Arechiga has been researching what happened in Chavez Ravine, and her family. On her Facebook page, she posts dozens of old photos of her family's fight to remain on the land. But she also includes happier moments, like her then-young grandmother's wedding, celebrated with neighbors. When his son goes to a Dodgers game, all Lou Santillan asks is that he bring him a bag of peanuts. Lou doesn't care about the team, but he can't help but feel a connection to the stadium. "There's an old Mexican custom that where you're born, the umbilical cord is buried. Mine's buried under third base," Lou said. "And I hate home runs, 'cause every time they step on third base, my stomach hurts." Sitting just yards from the parking lot of the pretty stadium — underneath which many of their happiest and saddest memories are buried — his friends roared with laughter. "When you see Louie, tell him that Al said that they should have buried him and left the umbilical cord out there," Zepeda said. "He should have been buried there, not the cord!" May 8, 1959: Aurora Vargas is carried by Los Angeles County Sheriff's deputies after her family refused to leave their house in Chavez Ravine. The photo was taken by Los Angeles MirrorNews photographer Hugh Arnott. 1/7 Chavez Ravine evictions May 8, 1959: Los Angeles County Sheriff’s deputies carry Mrs. Aurora Vargas from a house during the eviction of residents in Chavez Ravine. Most residents of Chavez Ravine had been relocated in the early 1950s, but a proposed public housing project was scrapped. The City of Los Angeles obtained the property, then traded the land to the Los Angeles Dodgers for the old Wrigley Field property in South Los Angeles. In 1959, with construction of Dodger Stadium slated to begin, negotiations with holdout Chavez Ravine residents failed, leading to evictions. Under a headline “Chavez Ravine Family Evicted; Melee Erupts,” the Los Angeles Times reported on May 9, 1959: There was a melee in Chavez Ravine yesterday as forcible eviction of a few residents there began. The action erupted only seconds after an army of sheriff’s deputies, accompanied by three large moving vans, arrived at the Arechiga family’s residences at 1767 and 1771 Malvina St. The deputies. led by Capt. Joe Brady, were armed with a writ of possession recently issued against the Arechigas by the Superior Court. According to City Atty. Roger Arnebergh, the Arechigas have been occupying the property rent-free since 1953 following its acquisition by condemnation by the City Housing Authority in 1951. The city purchased the property in 1955. It is intended to be part of a recreational facility that will include a baseball park for the Los Angeles Dodgers. It has been a long skirmish. And yesterday the battle was joined in earnest. It including a screaming, kicking woman (Mrs. Aurora Vargas, 38, daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Manual Arechiga) being carried from the house…children of the family wailing hysterically as their sobbing mother, Mrs. Victoria Angustian, 29, struggled fiercely in the grasp of deputies…the 72-year-old matriach of the family, Mrs. Avrana Arechiga, hurling stones at deputies as movers hustled away her belongings…an obstreperous former neighbor, Mrs. Glen Walters, screeching defiance at the deputies and finally being forcibly ejected from the battleground, handcuffed, and taken to a squad car….. Mrs. Vargas was the last to leave — making good her threat that “they’ll have to carry me.” The fray lasted about two hours. After the eviction, bulldozers leveled structures on the property. Members of the Arechigas family returned and lived on the property to protest of the eviction and bulldozing. The eviction was heavily covered by the media, both television and print. Several Los Angeles Herald Examiner images are online at the USC Digital Library. Search under ‘Chavez Ravine evictions.’