oc - Phoenix Center for Advanced Legal & Economic Public Policy

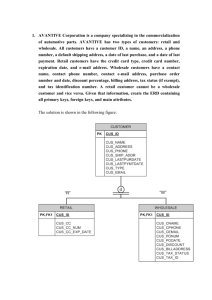

advertisement