Topic 1. An introduction to welfare economics

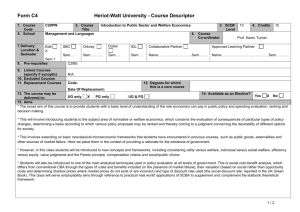

advertisement

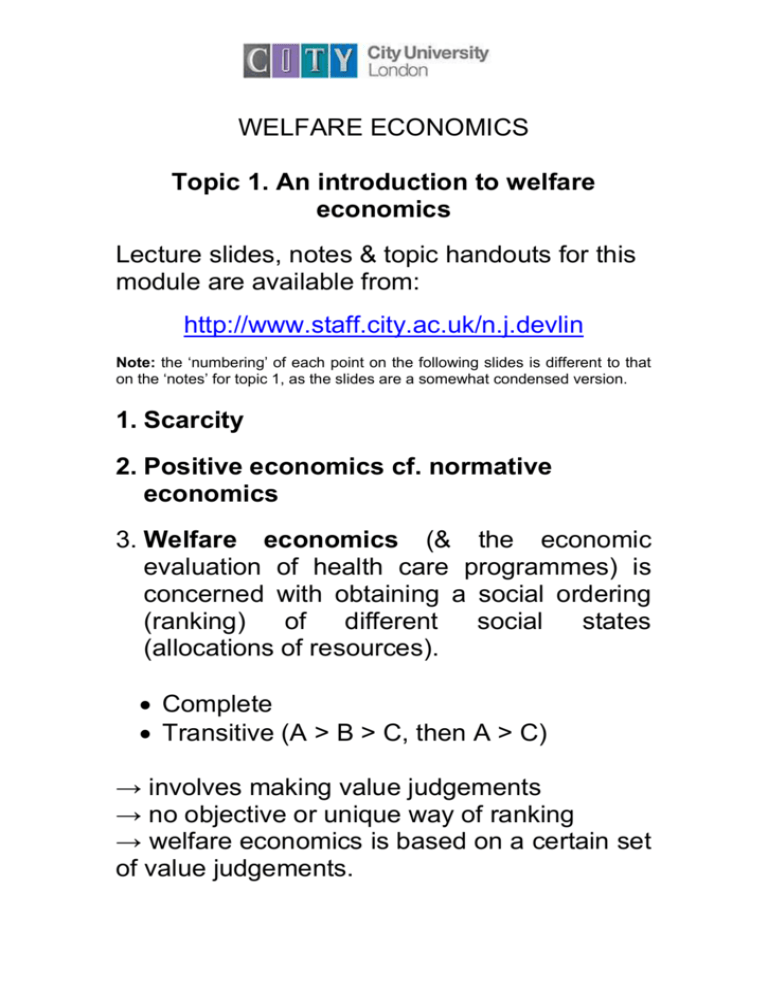

WELFARE ECONOMICS Topic 1. An introduction to welfare economics Lecture slides, notes & topic handouts for this module are available from: http://www.staff.city.ac.uk/n.j.devlin Note: the ‘numbering’ of each point on the following slides is different to that on the ‘notes’ for topic 1, as the slides are a somewhat condensed version. 1. Scarcity 2. Positive economics cf. normative economics 3. Welfare economics (& the economic evaluation of health care programmes) is concerned with obtaining a social ordering (ranking) of different social states (allocations of resources). Complete Transitive (A > B > C, then A > C) → involves making value judgements → no objective or unique way of ranking → welfare economics is based on a certain set of value judgements. 4. Welfare economics is based on the concept of economic efficiency Two main value judgements are involved: Individualism: Social orderings ought to be based on individual orderings of alternative states. Pareto principle 5. Theories of individual behaviour: rationality, utility & utility maximisation A formal statement of the household’s utility maximisation problem is given by: maximise U = u(x1, x2, …., xn ) subject to p x y n i 1 i i The solution the household’s utility maximisation problem is given by: MRS = dxdx pp 2 1 1 2 6. Economies consist of millions of individuals/households, with different tastes and different budget constraints. we need to distil welfare statements about the desirability of a social state from its effects on millions of different households. One option is to use the Pareto Principle. ‘aggregate’ individuals’ preferences using the ‘dominance’ notions contained in the PP. Weak Pareto criterion: if the utility of every household is higher in state x than state y then state x yields a higher level of societal welfare than state y and is preferred. Strong Pareto criterion: if the utilities of some households are higher in state x that in state y and the utility of no household is lower in state x than state y then state x yields a higher level of societal welfare than state y and is preferred. 7. Limitations: Only permits a partial ordering If state x is neither Pareto superior, nor Pareto inferior, not Pareto indifferent to state y then states x and y are Pareto non-comparable (states in which some households are made better off but others are made worse off in moving from one state to another). Is neutral to distributional concerns 8. Overcoming Pareto non-comparability: the compensation principle. Kaldor: state a is preferred to state b if the gainers from the move to state a can hypothetically compensate the losers so that everyone is better off. Hicks: state a is preferred to state b if the losers from the proposed move cannot hypothetically bribe the gainers not to make the move. 9. Problems with the compensation principle: the redistribution is hypothetical only redistribution is assumed to be costless the Pareto Principle is still unable to rank different Pareto optimal allocations relative to one another (there are still Pareto non-comparable states) the compensation principle may lead to contradictions ( the Scitovsky Paradox). 10. Pareto optimality and the general equilibrium of a competitive economy. The first fundamental theorem of welfare economics: under certain assumptions the allocation of goods and factors resulting from a competitive equilibrium is Pareto optimal. 11. The first fundamental theorem of welfare economics requires: efficient exchange of goods and services MRS MRS pp ** a b 1 2 efficient allocation of the production MRTS MRTS wr ** a factors of b efficient output choice (overall efficiency) MRS = MRT 12. Going beyond Pareto: A complete and consistent ranking of social states is called a social welfare ordering (SWO). the SWO can be represented by a social welfare function (SWF) that assigns a number to each social state so that they might be ranked. A SWF involves value judgements about the desirability of different social states. Value judgements are statements of ethics that cannot be found to be true or false on the basis of factual evidence. The value judgements found in a SWO may be weak (i.e. broadly accepted) or strong (i.e. controversial). 13. SWO possibilities are limited by informational requirements that pertain to the measurability and comparability of households’ utility. 14. In practice, markets ‘fail’, so that the conditions for the first fundamental theorem of welfare economics to hold are not met non-competitive behaviour externalities public goods informational asymmetries. 15. The role of Government to address market failures. to provide the institutional and legal framework under which the market operates to redistribute income to provide merit goods and limit/ban provision of demerit goods. 16. Public choice is the study of the political mechanisms and institutions that explain government and individual behaviour. It can be defined simply as the economic study of non-market decision-making. e.g. voting 17. Government intervention may not be desirable: the government requires some means of addressing the problem of preference revelation and the problem of aggregating preferences there may be government failures 18. Applied welfare economics: the empirical application of welfare economics measures of welfare change using a money metric. In a social CBA the appropriate decision rule is the net present value (NPV), given by NPV B(1 rC) , where r is the social time T t t 0 t t preference rate. 19. Extra welfarism. The admission of non-utility information into SWO. In CEA the desirability of a project is described in terms of a ratio of incremental costs to incremental benefits. (ICER) The proposed project should be implemented if the ICER is < critical costeffectiveness ratio.