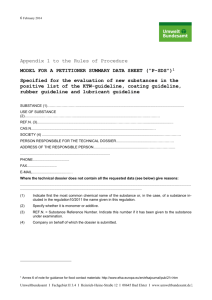

1 - HEU

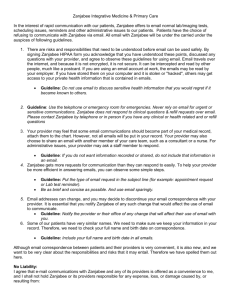

advertisement