Models of education: Steiner, Montessori and Dewey

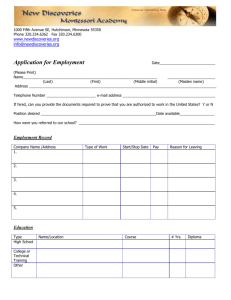

advertisement

Educational Culture and History of Child-centred Education: 1. The Age of Enlightenment, Liberalism and Human Rights. The 18th century was a period of political and scientific innovation, discovery and change. The revolutions in America (1776) and France (1789) accompanied a rethinking of the power of the traditional authorities of the Monarchy (Divine Right of Kings) and the Church (Papal Infallibility). (Background reading to this lecture can be found in the two Helen May extracts in your Course Reader, pp1-13 and the Colin Gibbs chapter on pp14- 27.) 2. Liberalism and Education: An emerging wealthy middle class were demanding a recognition of human rights. The philosopher John Locke argues that all people have natural rights to their own autonomy, a freedom of choice based on rationality and a respect for the truth, to determine the direction of their own lives. But rational autonomy requires that the individual’s choices must be informed by the most valid of knowledge. This means that each individual has a right to an education, and it is the responsibility of every liberal society to ensure that this happens. 3. Jean-Jacques Rousseau: Many of the ideas we encountered in the first lecture on Summerhill, have their origins in the model of education of Rousseau (1712-1778). (a) Like A.S.Neill, he sees society as a corrupting influence on the child, not something that the child should be socialised into. (b) He assumes that the child is innately good and wise. This is in stark contrast to the Churches Doctrine of Original Sin, which implies that like all humankind, the child is innately sinful and goodness must be disciplined into them, with physical punishment if necessary. (c) Rousseau rejects all punishment of children, just like Neill. Discipline is the cause of evil in a child, not the cure. (d) Like A.S. Neill, the founder of Summerhill, Rousseau believed that the freedom was both the method of education, and its purpose or aim. The child should be free to learn from their own experience, not the restrictions and guides of some teacher. Freedom is also the aim of education as it was for Neill who called it ‘self regulation’. Rousseau called it “the well-regulated liberty” that arises when a child is left free to do those things of which he is able. (e) Child-centred education means letting the nature of the child be the teachers guide. Rousseau is the first educator to see that the child’s inner nature emerges in stages from within the child. All subsequent child-centred educators (including A.S. Neill, and Maria Montessori) make this same assumption about the human nature of the child. This is the essential core of all child-centred education. 4. Johann Pestalozzi: A number of other key themes of child-centred education can be traced back to Pestalozzi, who was himself influenced by Rousseau. (a) He emphasises the importance of a family atmosphere of love and acceptance in the learning environment which we see at Summerhill. (b) He also stresses learning is initiated through the child’s own activity and engagement with the world of the senses (sight, touch, hearing, smell, and the kinaesthetic sense of movement), rather than through abstract learning. (c) Pestalozzi sees the process of education as one of growth, a theme that we will meet again when we look at John Dewey’s model of education. Pestalozzi looks at the child as like a plant that will grow if they are nurtured in an enriching context of learning. 5. Friedrich Froebel : The German educationist Froebel (1782-1852) was similarly influenced by Rousseau and Pestalozzi. (a) Froebel picks up Pestalozzi’s metaphor of the child as a growing plant. In fact, this idea is contained in his name for the pre-school which ‘children’s garden’ or as it is said in German, “kindergarten”. The kindergarten was envisaged a bridge between the home and the more formal school and the movement spread world-wide. The first free kindergarten was established in Dunedin in 1889. (b) Froebel advances child-centred educational thinking by stressing education through the child’s activity and play. He envisaged play not simply as recreation, but as children’s work. Play, for Froebel is an outward expression of the intellectual and spiritual building of the child’s mind. (c)Froebel sets out a series of quite distinct stages of development of the child’s nature “unfolding” like a flower blossoms across the ages of three to six: infancy, early childhood and childhood. As we shall see, Montessori picks on this idea of stages of development, as the child’s nature emerges and grows. (d) He also begins to set out a curriculum content and methods for children in these early years. He invented a series of geometric playthings that were to be introduced to the child in a particular order or sequence. He called these his (i)”gifts” and they were designed to stimulate the child’s senses, their imagination, and their intelligence. The soft knitted ball, for the infant, geometric shapes (a wooden ball, a cube and a cylinder. We will see how Montessori develops this idea shortly. In both cases these educators are emphasising the importance of play and activity learning. The second invention of Froebel’s early childhood curriculum was his (ii)“occupations”, as he called them. These were a sequence of handicraft activities such as drawing, paper-folding, sewing and construction, along with indoor and outdoor play, gardening, songs, dance and play. Maria Montessori’s Model of Education Educational, historical and cultural context: Maria Montessori (1870-1952) Italian doctor, feminist and socialist. Educated in the male-dominated profession of medicine. Worked as a paediatrician in ‘asylums’ in Rome. Studied the work of Jean Itard who believed in taking a scientific approach to the teaching of children with special needs. He stressed the importance of careful observation and experimentation in education. Also the ideas of Edward Seguin, who developed systematic training routines for ‘mentally defective’ children. He had developed special teaching materials for training the child’s senses and manipulative skills. (i) Scientific observation, experimentation, (ii) systematic skills development and (iii) the development of the senses became key features of her approach to the education of all children. 1907: Montessori opened a school called the Casa dei Bambini (House of Children) in a working class area of San Lorenz. Children were accepted from the age of three. In this relaxed and joyful environment, children learned (i) the practical life skills of everyday living, (ii) sensorial experiences and (iii) language education (including reading.) Curriculum Content: Practical life education. This section of the curriculum emphasises the developing routines of (i) caring for oneself, eg. Dressing oneself including dressing frames, shoe polishing, personal hygiene, all designed to promote independence. (ii) caring for the classroom eg domestic habits like dusting, cleaning windows, polishing, tidying the classroom. Montessori believed that child enjoy this. They are process-driven, not outcome-driven.(Agree?) (iii) caring for each other. eg the development of courtesy, sharing, manners, naturally flows from the affection that grows in this orderly envirionment. (Agree?) Sensorial education: A distinctive feature of Montessori classrooms and centres is the sensorial materials, designed to heighten the child’s sensitivity of all the senses: visual, auditory, tactile, smell, taste, and kineasthetic awareness. These are aesthetically appealing and graded to progressively challenge the child’s ability to discriminate, and self-correct where necessary. eg. cylinder blocks, for visually and grading size, eg. tonal bells to sequence pitch form high to low, eg. smelling bottles (sour to sweet). eg.classification of natural objects, eg leaf shapes Children also learn the language that accompanies these distinctions. This process of observing, sequencing, and classifying is at the very heart of logical scientific method. Academic learning: Reading begins really early, sometimes from the age of 3 years. (Compare with Steiner) . Reading emerges from writing. Children come to recognize letters and words as having sounds and meaning by first shaping letters by touch. eg sandpaper letters are traced with the finger. Phonic awareness. Children learn by analyzing the individual letters and sounds. It is the very opposite of the whole language approach to Reading, used in N.Z. Command cards: Sentences are analysed, broken up, and colour-coded on cards into verbs (red) nouns (black) etc. Children can use the to construct sentences. Mathematics learned using a wide range of ingenious materials and apparatus, designed to render abstact number accessible to the senses. eg number weights, rods, test-tube division, scales for equations. An analytical approach to content. Analysing the ‘big picture’ into its parts, and building the parts into the whole. Curriculum methods: Activity-based learning.Learning through the senses. The role of the teacher:Individualising programmes. Teachers make careful observations and notes on the progress of each child, judging when and how it to make the next developmental step, or introduce some new material. Repetition is an important step in developing mastery. The learning envirionment is carefully prepared. Only the appropriate materials are available to the child. The teacher ‘directs’ the order of learning. Children will work in groups, but only when the task is suited to their learning. Group work is not the norm. (Do you agree with this practice?) The learning envirionment is calm, focussed and attractive, not over-stimulating. Aims, objectives and educational values: Montessori teachers aim for the ‘normalised child’. Features: focused, curious, intellectually absorbed, cooperative, organized, calm, self-motivated, and free. Freedom implies a discipline from within, engaging with ones own activity and expressing an inner ‘urge’ for order. Assumptions about Human Nature: Children have absorbent minds. Learning is a natural effect of interaction with the envirionment. Sensitive Periods: There are times when children are more susceptible to different types of learning. Miss that period, and learning becomes much harder. -language -social manners -order -sense refinement -physical skills. Biologically imprinted ‘urges’ : These are expressions of the child’s ‘horme’. This is an inner life force to develop the capacities with which one is born. These urges are freed by the process of education. All children have natural urges for, Language Order Classification Exploration Manipulation Repetition and mastery Exactness Abstraction Work Self-perfection. But only a well ordered education will free them. (Agree?) Assumptions about worthwhile knowledge: Montessori education values these forms of knowledge: -ordering -sequencing -analysing -matching -classification -discrimination of similarities and differences. While it by no means down-plays the holistic (big picture) knowledge, it is very rational, logical, and scientific in its focus. Montessori emphasises an empiricist view of worthwhile knowledge. Empiricism is the epistemological theory that views knowledge as based upon sense experience. Empiricism takes a reductionist and analytical approach to worthwhile knowledge, (of which, Science is the best example.) This is the very opposite of Steiner’s holist approach to worthwhile knowledge, (of which, Art is the best example.) John Dewey’s Model of Education. Educational, historical and cultural context: John Dewey (1859-1952) …a biographical note. He was born in Burlington, Vermont. (USA) . Father was a proprietor of a general store, while mother instilled a passion for education. He did a Bachelor’s degree and trained as an elementary school teacher, working in rural schools in Pennsylvania and Vermont. He left teaching, went to John Hopkins University where he completed a PhD in Philosophy in 1884, and lectured at Michigan and University of Chicago where he received the Chair in Philosophy, Psychology, and Education in 1902. While there, he developed a ‘laboratory school’ where he experimented with new approaches to education. From 1904 until 1930 he was Professor of Philosophy at Columbia University in New York city. Over his lifetime he published over 1000 books and articles including Democracy and education (1916) which revolutionised educational thinking around the world, including New Zealand where his influence can still be seen today. His lifetime spanned nearly a century of radical social, political, and economic change in American (and indeed New Zealand history. This influenced his educational theory, and school practice around the world. How come? The frontier society and industrialization in USA and NZ. Frontier (or pioneer) societies in colonies and new lands throughout the world were: Cohesive interdependent communities. Work was meaningful and Immediately relevant to real human needs. Industrialisation of these societies meant that workers found their work Less meaningful, more repetitive More specialised and pointless Lacking a sense of community leading to a feeling of isolation and alienation. Education in industrialised societies was similarly becoming Meaningless, Specialised and pointless, Lacking a sense of community Leading to a feeling of learner isolation and alienation from any sense of purpose of the schooling activities. Against Formalism: Dewey was critical of subject-centred (or teacherdirected) education because it was not connected to the interests of children. and Against Naturalism: Dewey was critical of child-centred education (such as Steiner and Montessori schooling) too, because it merely followed the inner wants and urges of individual children. This was too disconnected from the needs of the learning community and wider society. Advocates Progressivism: Dewey argues that true education is experience-centred. That is to say, education should emerge from children experiencing the solving of problems and following the on-going interests that are immediate and meaningful to the community of the classroom….problem based learning. Dewey’s concept of experience: Typically we talk about an experience of a problem as something happens to us, as if we are quite passive..it simply washes over us ,like a wave. Maybe we worry about it but nothing changes. For Dewey, ‘experiencing’ a problem also means the active engagement in trying to find a solution to that problem. He identifies this as intelligent problem solving Curriculum Content: Interests and problems: Dewey does not specify any particular content. Follow the real interests and problems of children inlearning community of the classroom. While they are researching of these interesting problems, it will become necessary to develop knowledge skills and attitudes. Means, ends and ends-in-view: But knowledge, skills and attitudes of the traditional subject areas ( literacy, numeracy, science, social studies etc) are not ends in themselves. Rather, these will become the ‘tools’ that the learner can maintain as the means to future problem solving ends. Learning requires a purpose or end-in-view to make it meaningful to the learner. Habits: The learning outcome which is treated an end in itself, is merely a habit of the mind, because it is disconnected from its meaning in the solution of a real problem. The only habits worth developing are the habits of intelligent inquiry…problem solving skills and attitudes. Curriculum Methods: Problem-based learning begins with an interest or problem encountered by the learners. Learning occurs in the context of the activities of resolving that interest or problem that becomes their project. Project Method entails ‘experiencing’ the problem. ‘Experiencing’ a problem or interest means researching that problem or interest. Steps of experience: 1. Awareness of the problem or area of interest. 2. Clarification of the problem or area of interest. 3. Hypothesising possible solutions of procedures. 4. Anticipating possible outcomes in discussion. 5. Testing the hypothesis or procedure in practice. 6. Evaluating the outcome in resolving the problem. Role of the teacher: The teacher is actively involved in facilitating the process, but does not dominate it. Their role is help sequence the inquiry, to optimise the groups chances of experiencing a satisfying outcome. -authoratative not authoritarian. The role of the problem solving group: All members of the group share ownership of the problem, the activity, and the outcome. The democracy of the problem-solving group. Aims, objectives and educational values: Steps or ‘spiral’ of experience? Growth: The aim of education is growth, and the aim of growth is more growth. Growth means maintaining a continuity of experience. “Education, therefore, is a process of living and not a preparation for future living.” (My pedagogic creed, p6) Dewey aims at developing the habits of intelligent problem-solving, which is an inquiring attitude to life. Democracy and education: Education is a social process. Shared inquiry is more powerful than individual inquiry, and there is shared ownership of the outcome of that inquiry. Education, like research is democratic to its very core. Question: How does this fit with NZ’s highly individualist approach to education, where grades and qualifications are awarded to individuals, not groups? Assumptions about Human Nature and Knowledge: Experience : Dewey’s critique of the subject-centred view of experience. - assumes an unchanging world…false. - assumes humans can have veridical perception. ie seeing the world as it really is, without interpretation….false. - assumes that experience is a passive process….false. - assumes an ‘empty bucket’ theory of the mind. Dewey’s critique of the child-centred view of experience. -assumes that experience is outward expression of an inner reality…false. Dewey’s Pragmatic view of knowledge and human experience: Experience is both active and passive . - trying and undergoing experience -assumes that the world is constantly changing. What the child will need in the future, is the ability to ‘experience’ (ie solve problems in ) their world. The curriculum cannot be fixed and unchanging. -assumes that experiencing is an interaction with reality. -assumes that interactive experience, itself alters the child’s reality. -assumes that the child passively experiences their effect of the changes they make on the world, - and then actively reflects on the changes they have made - and then adapts their future action. Experience is a continuous responsive self-adapting reality-changing process of creating meaningful problemsolving strategies for dealing with the child’s own world. Instrumentalism: For Dewey, knowledge is not true or false. It is either meaningful or meaningless as a tool for solving problems. What we call ‘knowledge’ is a tool or instrument for exploring our world….hence , “Instrumentalism”. It does not make sense to say that known experiences are true or false, any more than it makes sense to say that a tool (eg a spade or a lawn mower) is true or false. It either helps to solve the problem or it doesn’t . “If the only tool you have is a hammer, you treat the whole world as a nail.” (Gregory Bateson.)