Cash bail - The Law Reform Commission of Hong Kong

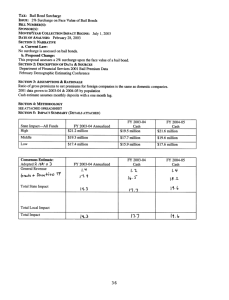

advertisement