CT-J-InformalFallacies

advertisement

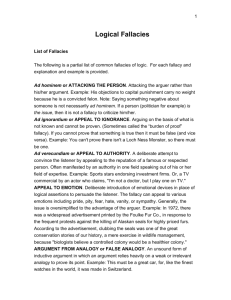

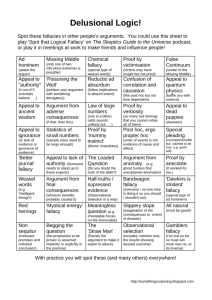

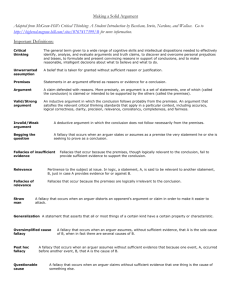

J-reading: Arguments: Rhetorical Fallacies (Some examples from Bassham, Irwin, Nardone, & Wallace, Critical Thinking, 143-155, 166-177.) To speak generally, a fallacy is a short-circuit in reasoning wherein the premises do not logically support the conclusion. In this respect, a logician will often refer to a faulty deductive argument as fallacious. In what follows we will deal with the more common phenomenon of rhetorical fallacies: attempts to persuade an audience by means of emotion instead of relevant reasons. These are more at home in inductive arguments. It is when these techniques are irrelevant (or not relevant enough) as support for a conclusion that they fit the standard definition of fallacy, but it must be born in mind that not every use of emotion is irrelevant to an argument’s conclusion. When I told my wife that she should marry me because I love her, this is both attempting to persuade her emotionally and perfectly relevant to the issue of whether she should marry me. In this regard, the point of discussing these techniques is not aimed at giving you a bunch of technical vocabulary. The real point of this reading is twofold: First, making yourself familiar with these different rhetorical techniques can help you be more active in detecting them when they occur in your daily life. (For example, you may soon find the mass media and advertisements either too ridiculous or too nauseating to pay any attention to.) Second, these issues help us refine our more global ability to discern what is relevant and irrelevant to an argument. 1. Appeal to Force or Fear Fear is a powerful motivator - so powerful that it often causes us to think and behave irrationally. The fallacy of appeal to force is committed when an arguer threatens harm to a reader or listener and this threat is irrelevant to the truth of the arguer's conclusion. Here are three examples: You really need the new Mercedes, or else people will think you’re unsuccessful. I'm sure you'll agree that we are the rightful rulers of the San Marcos Islands. It would be regrettable if we had to send armed forces to demonstrate the validity of our claim. This gun control bill is wrong for America, and any politician who supports it will discover how wrong they were at the next election. In each of these examples, the scare tactics employed provide no relevant evidence that supports the stated conclusion. Of course, not all threats involve fallacies. Here are three examples: If you come home late one more time, then your allowance will be cut. Attend class regularly and do your homework or you’ll get a poor grade. President Kennedy to Soviet Premier Kruschchev: If you don't remove your nuclear missiles from Cuba, then we will have no choice but to remove them by force. If we use force to remove the missiles, that may provoke an all-out nuclear war. Neither of us wants an all-out nuclear war. Therefore, you should remove your missiles from Cuba. (paraphrased) These are logically relevant to the conclusion. 2. Appeal to Pity and Flattery An appeal to pity or flattery relies on the audience’s sympathies or egos to gain their consent, when such feelings, however understandable, are not logically relevant to the arguer's conclusion. 1 Here is an example: Actual e-mail I received: “I really need to pass philosophy, because I am already on probation and will get kicked out. You said I was really close to a D, so can’t you move me up to a C- like my art teacher did?” Such arguments may or may not be effective in arousing our sympathies. Logically, however, this argument is clearly fallacious, for the premises provide no relevant reasons to accept the conclusion. Are all arguments that contain emotional appeals fallacious? No, as the following examples illustrate: Felisha, your paper is genius. Can I have a copy of it to show to future students? I’m sorry, Jeff, but I wasn’t able to finish this assignment, because I had to undergo an emergency lobotomy as part of my parole agreement. Granny was asking about you the other day. She's so lonely and depressed since Grandpa passed away, and her Alzheimer's seems to get worse every day. She's done so much for you over the years. Don't you think you should pay her a visit? In these examples, the appeals to emotion are both appropriate and relevant to the arguers' legitimate purposes. Too often, however, people use emotional appeals to hinder or obscure rational thinking. 3. Appeal to the People or Popularity or Bandwagon We all like to feel loved, admired, recognized, valued, and accepted by others. A bandwagon argument is an argument that plays on a person's desire to be popular, accepted, or valued, rather than appealing to logically relevant reasons or evidence. Here are four examples: All the really cool kids at TVI smoke cigarettes. Therefore, you should, too. I can't believe you're going to the library on a Friday night! You don't want people to think you're a nerd, do you? There must be something to astrology. Millions of Americans can't be wrong. But all the sorority sisters agree that a “blondes only” policy is not racist. The basic pattern of these arguments is this: 1. Everybody (or a select group of people) believes or does X. 2. Therefore, you should believe or do X, too. This pattern is fallacious, because the fact that a belief or a practice is popular usually provides little or no evidence that the belief is true or that the practice is good. Popularity arguments are especially common in advertising. Not all appeals to popular beliefs or practices are fallacious, however, as these examples illustrate: In this country, it's considered rude to stand right next to a person on an elevator when there's nobody else in it. Therefore, if you don't want to be considered rude, you should move over next time that situation occurs. All of the villagers I spoke to said that the water here is too contaminated for drinking. These bandwagon appeals are not fallacious, because the premises are relevant to the conclusions. 2 4. Argument against the Person (Ad Hominem) The Ad Hominem fallacy attacks the person instead of using reasons to attack their claim or position. Here are two examples: If Governor Davis wants to increase gun control, then I’m against it, because he is the same guy who wants to build more power plants. Hugh Hefner, founder of Playboy magazine, has argued against censorship of pornography. But Hefner is an immature, self-indulgent millionaire who never outgrew the adolescent fantasies of his youth. His argument isn't worth a plugged nickel. Even if it is true that Hefner is a bad person, that doesn't mean he is incapable of offering good arguments on the topic of censorship. The attack on Hefner's character is simply irrelevant to the point at issue, which is the strength of Hefner's case against the censorship of pornography. This is a particular form of Ad Hominem that is called the Genetic Fallacy. This brand of Ad Hominem implies that a claim or argument is bad because of its source, as if the source completely determines the veracity of the claim. For instance, Hitler is often used as the epitome of the bad character, which I in no way deny, but that does not entail that if he claimed, “A circle is a round shape,” he must be mistaken. A similar technique is found in the charge that a person whose recommendations seem to contradict their own behavior must be mistaken in their recommendation. In other words, their argument is rejected because that person fails to practice what he or she preaches. This is referred to by several different names: the hypocrite fallacy, the “Look who’s talking” fallacy, or the tu quoque ("you too”) fallacy. Here are several examples: “You should quit smoking.” “Look who's talking! I'll quit when you do, Mr. Smokestack! President Clinton: We need to restore family values in the American entertainment industry. Our children's futures depend on it. Joe Q. Public: What incredible chutzpah! Why should we listen to anything that hypocrite has to say about "family values"? Presidential candidate Bill Bradley: When Al [Gore] accuses me of negative campaigning, that reminds me of the story about Richard Nixon, the kind of politician who would chop down a tree, then stand on the stump and give a speech about conservation. Arguments are good or bad not because of who offers them but because of their own intrinsic strengths or weaknesses. You cannot refute a person's argument simply by pointing out that he or she fails to practice what he or she preaches. However, it should be noted that there is nothing fallacious as such in criticizing a person's hypocritical behavior. For example: Jim: Our neighbor Joe gave me a hard time again yesterday about washing our car during this drought emergency. Patty: Well, he's right. But I wish that hypocrite would live up to his own advice. Just last week I saw him watering his lawn in the middle of the afternoon. Here, Patty is simply pointing out, justifiably, that their neighbor is a hypocrite. However, because she does not reject any argument or claim offered by the neighbor, no fallacy is committed. 3 Closely related to this hypocrite fallacy is the fallacy of two wrongs make a right. The fallacy of two wrongs make a right occurs when an arguer attempts to justify a wrongful act by claiming that some other act is just as bad or worse. Here are some examples: I don't feel guilty about cheating on Dr. Boyer's test. Half the class cheats on his tests. You can't blame Clinton for being unfaithful to his wife. Many presidents have had extramarital affairs. Why pick on me, officer? Nobody comes to a complete stop at that stop sign. Parent: Quit hitting your brother. Child: He pinched me. We have all offered our share of such excuses. But however tempting such excuses may be, we know that they can never truly justify our misdeeds. It is important to bear in mind, however, that not every personal attack is a fallacy. The fallacy of personal attack occurs only if (1) an arguer rejects another person's argument or claim and (2) the arguer attacks the person who offers the argument or claim, rather than considering the merits of that argument or claim. Consider some examples of personal attacks that aren't fallacies but might easily be mistaken for fallacies. Here are two examples: Millions of innocent people died in Stalin's ruthless ideological purges. Clearly, Stalin was one of the most brutal dictators of the twentieth century. Ms. Smith has testified that she saw my client rob the First National Bank. But Ms. Smith has twice been convicted of perjury. In addition, you've heard Ms. Smith's own mother testify that Ms. Smith is a pathological liar. Therefore, you should not believe Ms. Smith's testimony against my client. Here the characters of these persons are directly relevant to the claims being made. In the first example, attacking Stalin’s character is the very point at issue. In the second, Ms. Smith’s character is a relevant reason to disrespect Ms. Smith as a credible witness. Because the arguer's personal attacks are relevant to the issues, no fallacy is committed. Another version of the fallacy of personal attack is the fallacy of attacking the motive. Attacking the motives is the error of criticizing a person's motivation for offering a particular argument or claim, rather than examining the worth of the argument or claim itself. Here are two examples: Ned James claims that he can prove that Mayor Babcock has embezzled city funds. But James is just trying to get back at the mayor for firing him from his job as city controller. Barbara Simmons, President of the American Trial Lawyers Association, has argued that punitive damage awards resulting from tobacco litigation should not be limited. But this is exactly what you would expect her to say. Trial lawyers stand to lose billions if such punitive damage awards are limited. Therefore, we should ignore Ms. Simmons's argument. This pattern of reasoning is fallacious because people with biases or questionable motives do sometimes offer good arguments. You cannot simply assume that because a person has a vested interest in an issue, any position he or she takes on the issue must be false or weakly supported. It is important to realize, however, that not all attacks on an arguer's motives are fallacious. Here are two examples: 4 Burton Wexler, spokesperson for the American Tobacco Growers Association, has argued that there is no credible scientific evidence that cigarette smoking causes cancer. Given Wexler's obvious bias in the matter, his arguments should be taken with a grain of salt. "Crusher" Castellano has testified that mob hit man Sam Milano was at the movies at the time mob informer Piero Roselli was gunned down. But Castellano was paid $30,000 by the mob for his testimony. Therefore, Castellano's testimony should be seriously questioned. Both of these arguments include attacks on an arguer's motives. However, neither of the arguments is fallacious. Both simply reflect the commonsense assumption that arguments put forward by arguers with obvious biases or motivations to lie need to be scrutinized with particular care. 5. Straw Man The straw man fallacy is committed when an arguer distorts an opponent's argument or claim in order to make it easier to attack. I like to think of the “straw man” as a boxing metaphor. The real contending fighter will take on the strongest competition to display his/her prowess. If a boxer chooses to only take on obviously inferior opponents, they haven’t proved a thing about their strength if they’ve only knocked out opponents who were no tougher than a man of straw (i.e., scare crow). Here are two examples: You are pro-choice. So you want abortion to be like birth control? You are pro-life. So you want teenagers using coat hangers and more babies in trash cans? Straw man fallacies are extremely common in politics. For example: Mr. Goldberg has argued against prayer in the public schools. Obviously Mr. Goldberg advocates atheism. But atheism is what they used to have in Russia. Atheism leads to the suppression of all religions and the replacement of God by an omnipotent state. Is that what we want for this country? I hardly think so. Clearly Mr. Goldberg's argument is nonsense. Senator Biddle has argued that we should outlaw violent pornography. Obviously, the Senator favors complete governmental censorship of books, magazines, and films. Frankly, I'm shocked that such a view should be expressed on the floor of the United States Senate. It runs counter to everything this great nation stands for. No senator should listen seriously to such an outrageous proposal. Take the second argument. This argument distorts the senator's view. His claim is that violent pornography should be outlawed, not that there should be complete governmental censorship of books, magazines, and films. By misrepresenting the senator's position and then attacking the misrepresentation rather than the senator's actual position, the arguer commits the straw man fallacy. 6. Red Herring In a Red Herring the reasons given actually support a different claim than the one at issue. When this is used strategically, an arguer tries to sidetrack his or her audience by raising an irrelevant issue and then claims that the original issue has effectively been settled by the irrelevant diversion. The fallacy apparently gets its name from a technique used to train English foxhounds. A sack of red (i.e., smoked) herrings was dragged across the trail of a fox to train the foxhounds to follow the fox's scent rather than the powerful distracting smell of the fish. In a similar way, an arguer commits the red herring fallacy when he seeks to distract his audience by raising an irrelevant issue and then 5 claims or implies that the irrelevant diversion has settled the original point at issue. Here are some examples: My wife: We should start being vegetarians. The Martin’s are vegetarians, and they are both on a strict budget and seem like a neat family. You said it yourself that Anna is a good cook and has raised some nice kids. Americans do not drink too much alcohol. Prohibition led to a dramatic increase in organized crime and yet it was still available on the black market. It is just not practical to outlaw drinking. Many people criticize Thomas Jefferson for being an owner of slaves. But Jefferson was one of our greatest presidents, and his Declaration of Independence is one of the most eloquent pleas for freedom and democracy ever written. Clearly, these criticisms are unwarranted. Critics have accused my administration of doing too little to save the family farm. These critics forget that I grew up on a farm. I know what it's like to get up at the crack of dawn to milk the cows. I know what it's like to work in the field all day in the blazing sun. Family farms are what made this country great, and those who criticize my farm policies simply don't know what they're talking about. 7. Appeal to Unqualified Authority The appeal to unqualified authority fallacy is a variety of the argument from authority and occurs when the cited authority or witness is not a trustworthy source. There are several reasons why an authority or witness might not be trustworthy. The person might lack the requisite expertise, might be biased or prejudiced, might have a motive to lie or disseminate "misinformation," or might lack the requisite ability to perceive or recall. The following examples illustrate these reasons: Dr. Bradshaw, our family physician, has stated that the creation of muonic atoms of deuterium and tritium hold the key to producing a sustained nuclear fusion reaction at room temperature. In view of Dr. Bradshaw's expertise as a physician, we must conclude that this is indeed true. This conclusion deals with nuclear physics, and the authority is a family physician. Because it is unlikely that a physician would be an expert in nuclear physics, the argument commits an appeal to unqualified authority. It is possible that he could be an expert in more than one field, but we are right to not accept his authority if we all we know is that he is a physician. David Duke, former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, has stated, "Jews are not good Americans. They have no understanding of what America is." On the basis of Duke's authority, we must therefore conclude that the Jews in this country are un-American. As an authority, David Duke is clearly biased on this issue, so his statements cannot be trusted. James W. Johnston, Chairman of R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, testified before Congress that tobacco is not an addictive substance and that smoking cigarettes does not produce any addiction. Therefore, we should believe him and conclude that smoking does not in fact lead to any addiction. If Mr. Johnston had admitted that tobacco is addictive, it would have opened the door to government regulation, which could put his company out of business. Thus, because Johnston had a clear motive to lie, we have good reasons for distrusting his statements. If he is telling the truth, we will need to 6 see more evidence to overcome our suspicions. And, in this particular case, his position is so implausible, based on what we know about cigarettes, that he has a large burden of proof to overcome. 8. Appeal to Ignorance When we lack evidence for or against a claim, it is usually best to suspend judgment -- to admit that we just don't know. When an arguer treats a lack of evidence as positive evidence that a claim is true or false, he or she commits the fallacy of appeal to ignorance. More precisely, the fallacy of appeal to ignorance occurs when an arguer asserts that a claim must be true because no one has proven it false, or, conversely, that a claim must be false because no one has proven it true. Here are two examples: Astrology has not been disproven in 2,000 years, so it must be accurate. There isn't any intelligent life on other planets. No one has proven that there is. Is it ever legitimate to treat a lack of evidence for a claim as evidence that the claim is false? In some rare cases, yes. One exception, in particular, should be noted. Sometimes the fact that a search hasn't found something is good evidence that the thing isn't there to be found. For example: We've searched this car from top to bottom looking for the stolen jewels and no trace of the jewels has been found. Therefore, probably the jewels aren't in the car. It is important to keep in mind, however, that this "fruitless search" exception applies only when (1) a careful search has been conducted, and (2) it is likely that the search would have found something if there had been anything there to be found. 9. Hasty Generalization A Hasty Generalization makes a general conclusion from an inadequate sample of evidence or too quickly asserts that all or most things of a certain kind have a certain property or characteristic. Examples: Another plane crashed. Cars are way safer. Plays are boring. Germans are very methodical. I asked 3 of my friends that failed your class, and they said you grade too hard. It should be noted that not every argument that 'jumps to a conclusion" is a hasty generalization. For example: That is the second time I have tried that brand of diet root beer. I just don’t like it at all. Here the small sample is not a problem for the generalization, because we assume that the root beer is made quite nearly the same way in every batch of the product. 7 10. False Cause The fallacy of False Cause uses a coincidental occurrence to explain an event. This will usually involve assuming that one thing caused another simply because the two things either occur together somewhat frequently or simply happened after one another. Now, it must be said that this is most clearly a fallacy when there is insufficient evidence of there being a causal connection between the events. Sometimes, this lack of evidence is all the more obvious when some third thing is the more likely cause or it is fairly obvious that the cause is much more complex than the arguer’s simplistic conclusion. If you have a cold, you have to drink some ginseng tea. Every time I get the sniffles, I drink a cup, and my cold is gone within a day or two. On Monday I stayed up all night partying, had eggs for breakfast, and failed my calculus test. On Wednesday I stayed up all night partying, had eggs for breakfast, and failed my biology test. Obviously, to do better on tests, I must stop eating eggs for breakfast. Violent crime has declined steadily in recent years. Obviously, tougher imprisonment policies are working. During the past two months, every time that the cheerleaders have worn blue ribbons in their hair, the basketball team has been defeated. Therefore, to prevent defeats in the future, the cheerleaders should get rid of those blue ribbons. 11. Slippery Slope We often hear arguments of this sort: "We can't allow A, because A will lead to B, and B will lead to C, and we sure as heck don't want C" Arguments of this sort are called slippery-slope arguments. Often, such arguments are fallacious. We commit the slippery-slope fallacy when we claim, without sufficient evidence, that a seemingly harmless action, if taken, will lead to a disastrous outcome. Such a chain of consequences is only reasonable if the causes of each are very similar. There has to be a good reason that A will lead to C. Here are several examples: If they are allowed to catch people who run red lights using automated cameras, pretty soon they’ll have cameras in our bathrooms. Bans on so-called "assault weapons" must be vigorously opposed. Once the gun-grabbing liberals have outlawed "assault weapons," next they'll go after handguns. After that, it will be shotguns and hunting rifles. In the end, law-abiding citizens will be left totally defenseless against predatory criminals and a tyrannical government. In a recent letter to the editor, Stella Davis argued that we should legalize same-sex marriages. But allowing same-sex marriages would undermine respect for traditional marriage. Traditional marriage is the very foundation of our society. If that foundation is destroyed, our whole society will collapse. Socialized medicine really frightens me. Once you start down that road, there's no turning back. A communist regime is the inevitable result. It is important to note that not all slippery-slope arguments are fallacious. Sometimes there are good reasons for thinking that an undesirable or even catastrophic series of events may result from a seemingly harmless first step. For example: Brad, I know you've been shootin' up heroin. Man, don't you know what that stuff can do to you? First, you shoot up "just when you need a rush." After a while, you become addicted to the 8 stuff. You lose your job, even steal from your best friend to feed the habit. Eventually you wind up strung out in some detox center. Listen to me, I'm your best friend. Think about what you're doing. In this case, there are perfectly sound reasons for avoiding an all-too-genuine slippery slope. 12. Weak Analogy The fallacy of weak analogy occurs when an arguer compares two (or more) things that aren't really comparable in relevant respects. For example: Alan is tall, dark, and handsome, and has blue eyes. Bill is also tall, dark, and handsome. Therefore, Bill probably has blue eyes, too. The basic pattern here is this: 1. A has characteristics w, x, y, and z. 2. B has characteristics w, x, and y. 3. Therefore, B probably has characteristic z, too. Many arguments with this pattern are perfectly good arguments. For example: Alice lives in a mansion, drives a Rolls Royce, wears expensive jewelry, and is rich. Beatrice also lives in a mansion, drives a Rolls Royce, and wears expensive jewelry. Therefore, Beatrice probably is rich, too. This is a good argument from analogy because people who live in a mansion, drive a Rolls Royce, and wear expensive jewelry are usually rich. However, there is no relevant connection between being tall, dark, and handsome on the one hand, and having blue eyes on the other. 13. Begging the Question The fallacy of begging the question is committed when the evidence for the claim either relies on the very claim it is trying to prove or else is just a restatement of the original claim. God exists, because the Bible assumes it, and why would God lie about Himself? Tolerance is a key moral value, because we should be tolerant of other cultures. Clearly, terminally ill patients have a right to doctor assisted suicide. After all, many of these people are unable to commit suicide by themselves. Often the cause of the question-begging is that a key premise has been left out that does all of the key inferential work. In the last of the above examples, perhaps the author could have presented same compelling reason why being unable to commit suicide by themselves warrants physicianassisted suicide. 9 14. False Dichotomy or Black & White Fallacy The fallacy of false dichotomy is committed when an arguer reduces an issue to a choice between two options when, in reality, there are more than two possible options. Are you a complete slacker or did you complete the assignment on time? Look, the choice is simple. Either you support a pure free-market economy or you support a communist police state. 15. Suppressed Evidence and Proof Surrogate If an argument ignores key evidence, then the argument commits the fallacy of suppressed evidence. Most dogs are friendly and pose no threat to people who pet them. Therefore, it would be safe to pet the little dog that is approaching us now. If the arguer ignores the fact that the little dog is excited and foaming at the mouth (which suggests rabies), then the argument commits a suppressed evidence fallacy. The new RCA Digital Satellite System delivers sharp TV reception from an 18-inch dish antenna, and it costs only $199. Therefore, if we buy it, we can enjoy all the channels for a relatively small one-time investment. The ads for the Digital Satellite System fail to mention that the user must also pay a substantial monthly fee to the satellite company and that none of the local channels are carried by the system. Thus, if the observer takes the ads at face value and uses them as the basis for such an argument, the argument will be fallacious. Yet another form of suppressed evidence is committed by arguers who quote passages out of context from sources such as the Bible, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights to support a conclusion that the passage was not intended to support. Consider, for example, the following argument against gun control: The Second Amendment to the Constitution states that the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed. But a law controlling handguns would infringe the right to keep and bear arms. Therefore, a law controlling handguns would be unconstitutional. In fact, the Second Amendment reads, "A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed." In other words, the amendment states that the right to bear arms shall not be infringed when the arms are necessary for the preservation of a well-regulated militia. Because a law controlling handguns (pistols) would have little effect on the preservation of a well-regulated militia, it is unlikely that such a law would be unconstitutional. Quite often an author will even give a proof surrogate in place of this missing evidence. These are expressions that insinuate that the proof is “out there” or “not needed”. We have only to think of how advertising pretends to cite their sources with expressions lie, “Sources say..,” “Studies show…,” or “It is obvious that…”. Does a critical audience want to see this evidence for themselves? Yes, they should. 10 Everybody knows that men have a higher pain threshold than women. Peggy: “It is just a fact that philosophy is a complete waste of time.” 16. Equivocation The fallacy of equivocation is committed when a key word is used in two or more senses in the same argument and the apparent success of the argument depends on the shift in meaning. Fallacies of equivocation can be difficult to spot because they often appear valid, but aren't. Woman: All men are dogs. Man: Well, dogs are allowed to pee in public, so here goes... 17. Euphemism, Innuendo, and Hyperbole These last three fallacies are best understood as forms of rhetorical language than fallacious ways of arguing. In other words, these involve expressing claims in ways that strategically misinform or mislead the audience. I am introducing these mainly to aid your ability to describe forms of rhetorical techniques. The first, euphemism, uses a word or expression that is similar in meaning to the more literal meaning but connotes to the audience a much more positive sense of things. Our bombers delivered the packages to their targets successfully. Hugh Grant was arrested for having a relationship with a self-employed model. Bubba: “But, officer, I was just helping flossy (the sheep) over the fence.” Its sister concept is the dysphemism, where an expression is used that is close to the literal account but gives the audience a derogatory understanding. Innuendo is a technique where a speaker can imply a negative idea about something or someone but do not directly say it. The offensive content is as much in what they don’t say as it is in what they do say. All I can say is that I am a candidate that is not a flip-flopper. “I didn’t say the meat was tough. I said I didn’t see the horse that is usually outside.” –W.C. Fields. Hyperbole is an extreme exaggeration or overstatement. It is important, however, to only use the term hyperbole for grossly exaggerated claims. To say that “Michael Jordan is incredibly inventive when he drives the lane” is a lofty description, but it isn’t hyperbolic. A common use of hyperbole is when a hungry American says, “I’m starving.” 11