Ethan Frome - UJDigispace

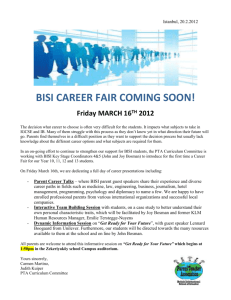

advertisement