DeLuca & Holburn

advertisement

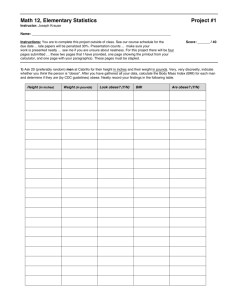

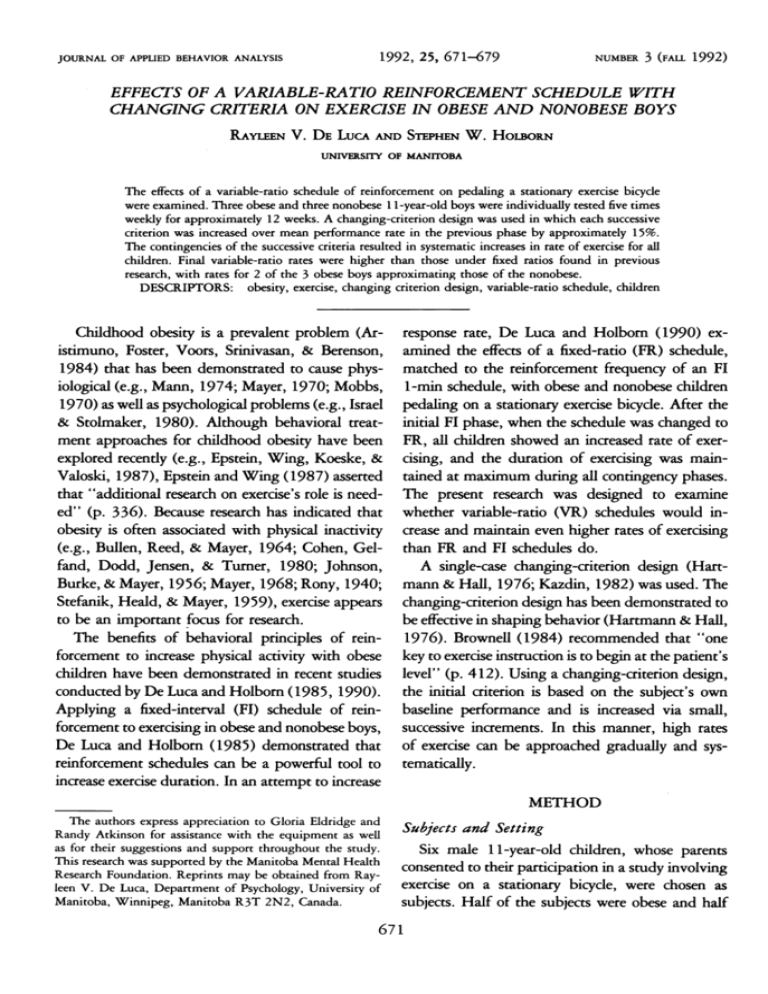

JOURNAL OF APPLIED BEHAVIOR ANALYSIS 1992)25,671-679 NUMBER 3 (FAu 1992) EFFECTS OF A VARIABLE-RATIO REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULE WITH CHANGING CRITERIA ON EXERCISE IN OBESE AND NONOBESE BOYS RAYLEEN V. DE LucA AND STEPHEN W. HOLBORN UNIVERSITY OF MANITOBA The effects of a variable-ratio schedule of reinforcement on pedaling a stationary exercise bicycle were examined. Three obese and three nonobese 11-year-old boys were individually tested five times weekly for approximately 12 weeks. A changing-criterion design was used in which each successive criterion was increased over mean performance rate in the previous phase by approximately 15%. The contingencies of the successive criteria resulted in systematic increases in rate of exercise for all children. Final variable-ratio rates were higher than those under fixed ratios found in previous research, with rates for 2 of the 3 obese boys approximating those of the nonobese. DESCRIPTORS: obesity, exercise, changing criterion design, variable-ratio schedule, children Childhood obesity is a prevalent problem (Aristimuno, Foster, Voors, Srinivasan, & Berenson, 1984) that has been demonstrated to cause physiological (e.g., Mann, 1974; Mayer, 1970; Mobbs, 1970) as well as psychological problems (e.g., Israel & Stolmaker, 1980). Although behavioral treatment approaches for childhood obesity have been explored recently (e.g., Epstein, Wing, Koeske, & Valoski, 1987), Epstein and Wing (1987) asserted that "additional research on exercise's role is needed" (p. 336). Because research has indicated that obesity is often associated with physical inactivity (e.g., Bullen, Reed, & Mayer, 1964; Cohen, Gelfand, Dodd, Jensen, & Turner, 1980; Johnson, Burke, & Mayer, 1956; Mayer, 1968; Rony, 1940; Stefanik, Heald, & Mayer, 1959), exercise appears to be an important focus for research. The benefits of behavioral principles of reinforcement to increase physical activity with obese children have been demonstrated in recent studies conducted by De Luca and Holborn (1985, 1990). Applying a fixed-interval (FI) schedule of reinforcement to exercising in obese and nonobese boys, De Luca and Holborn (1985) demonstrated that reinforcement schedules can be a powerful tool to increase exercise duration. In an attempt to increase The authors express appreciation to Gloria Eldridge and Randy Atkinson for assistance with the equipment as well as for their suggestions and support throughout the study. This research was supported by the Manitoba Mental Health Research Foundation. Reprints may be obtained from Rayleen V. De Luca, Department of Psychology, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3T 2N2, Canada. response rate, De Luca and Holborn (1990) examined the effects of a fixed-ratio (FR) schedule, matched to the reinforcement frequency of an F1 1-min schedule, with obese and nonobese children pedaling on a stationary exercise bicyde. After the initial F1 phase, when the schedule was changed to FR, all children showed an increased rate of exercising, and the duration of exercising was maintained at maximum during all contingency phases. The present research was designed to examine whether variable-ratio (VR) schedules would increase and maintain even higher rates of exercising than FR and F1 schedules do. A single-case changing-criterion design (Hartmann & Hall, 1976; Kazdin, 1982) was used. The changing-criterion design has been demonstrated to be effective in shaping behavior (Hartmann & Hall, 1976). Brownell (1984) recommended that "one key to exercise instruction is to begin at the patient's level" (p. 412). Using a changing-criterion design, the initial criterion is based on the subject's own baseline performance and is increased via small, successive increments. In this manner, high rates of exercise can be approached gradually and systematically. METHOD Subjects and Setting Six male 11-year-old children, whose parents consented to their participation in a study involving exercise on a stationary bicycle, were chosen as subjects. Half of the subjects were obese and half 671 672 62RYLEEN V. DE LUCA and STEPHEN W. HOLBORN were of normal weight (as defined by age, height, and weight norms, Demirjian, 1980, and skin-fold thickness, Seltzer & Mayer, 1965). To qualify, obese children had to be at least 20% above average body weight for their age, sex, and height (Demirjian, 1980), had no medical problems that contraindicated exercise, were not taking medication that would affect body weight, and were not involved in a formal weight control program. The obese boys were at least at the 97th percentile for weight and ranged from 32% to 161.4% over the acceptable range for percentage body fat. All obese subjects were classified as "overfat" (Canadian Department of Health and Welfare [CDHW], 1984). The nonobese boys were at, or slightly below, the 50th percentile for weight. Two nonobese boys were within the acceptable range for percentage body fat for boys, and 1 was 5.5% over the acceptable range for percentage body fat and was dassified as "undesirable" (CDHW, 1984). The heights of all boys were within the normal range. All testing was conducted in the nurse's room of an elementary school in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Apparatus A CCM stationary exercise bicyde was programmed to ring a bell and to illuminate a red light simultaneously after each variable number (VR) of responses during the contingency phases. Lehigh Valley and BRS electromechanical modules were used for programming stimulus events and for recording responses and reinforcements. The bell and light were programmed via electromechanical timers and relay circuitry. Each wheel revolution constituted a response and was recorded on magnetic counters. Folding 183-cm partitions were used to obscure the equipment panels from the subject's view. A 7-W red light was mounted on the front middle panel of the bicyde in the subject's line of vision. Throughout the study, the tension of the bicyde was set at moderately low resistance (2.27 kg) for all subjects. Experimental Design A single-case changing-criterion design was employed (see Hartmann & Hall, 1976; Kazdin, 1982). Baseline data were taken for 3 obese and 3 nonobese boys for eight sessions until behavior appeared stable to visual inspection, after which the initial VR schedule was introduced. Eight sessions later, when responding was stable, the second VR subphase was introduced. Following another eight sessions, when stability was reached, the third VR subphase ensued for eight sessions. To exhibit fuiher control, a three-session return-to-baseline phase was followed by a final VR subphase at the previous criterion, which lasted for five sessions. Procedure Throughout the study, subjects were individually tested daily from Monday to Friday over approximately 12 weeks. The instructions given at the beginning of each session were identical for all subjects: "Exercise as long as you like." No further encouragement was given. Recording began when the subject began pedaling the bicyde. The experimenter was seated behind the equipment panels out of the subject's view. Sessions terminated when the subject dismounted from the bicyde or when 30 min had elapsed, whichever occurred first. Baseline. Prior to the first session, each child was asked if he would like to exercise five times weekly on the stationary bicyde. During the first session, following the consent of each subject to participate in the exercise program, the instructions "exercise as long as you like" were given. No stimulus changes occurred, nor was reinforcement administered during baseline. After eight sessions, the point system was introduced. Reinforcement survey. Reinforcement surveys (Cautela, 1977) were individually administered to each child during the first week of baseline. Ten items from the preferred categories were selected as back-up reinforcers. Subjects rated on a scale of 1 to 10 how much they liked each item. Higher costs were then assigned to the items with higher preference ratings. VR (first subphase). The VR schedule of reinforcement was implemented during the ninth session, after a stable baseline had been achieved. The mean number of revolutions per minute during the baseline was calculated for each subject. A separate VR REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULE ratio value was assigned to each subject during the initial VR phase on the basis of approximately a 15% increase over mean responding during baseline. For example, the obese subject who pedaled a mean of 60 revolutions per minute during baseline received a VR 70 schedule; the schedule for the nonobese subject, who pedaled a mean of 70 revolutions per minute during baseline, was VR 80. This manipulation ensured that the shifts in density of reinforcement would be similar for subjects and that the first criterion would not be overly stringent. Prior to beginning the first session of this phase, subjects were allowed to examine the 10 back-up reinforcers, tagged with the number of points necessary for purchase. Reinforcers induded a hand-held battery-operated game, kite, bicyde bell, flashlight, model car, model plane, puzzle, adventure book, and comic books. Subjects were advised that they could earn points by exercising on the bicyde to "buy" the items that they liked best. They were told that each time the bell rang and the light went on, they would earn a point. At the end of each session, the subject received a tally of the number of points he had earned during the session and the cumulative total to date. VR (second subphase). The second VR schedule of reinforcement was implemented during the 17th session, after stability had been achieved in the first VR subphase. A separate ratio value was assigned to each subject on the basis of a 15% increase over mean responding during the previous subphase. In other words, a different criterion for performance was specified for each subject, based on his performance in the previous subphase. VR (third subphase). The third VR schedule of reinforcement was implemented when stability was achieved for the second VR subphase. Again, a separate ratio value was assigned to each subject during the third subphase on the basis of a 15% increase over mean responding during the previous subphase. Return to baseline. To provide further evidence of experimental control, the return-to-baseline phase was implemented after eight sessions on the third VR subphase, when stability in responding had occurred, and was continued for three sessions. 673 Return to VR third subphase. The subjects were returned to their individual third subphase schedules for the last five sessions, which coincided with the last 5 days of school prior to summer vacation. Social validation. Each subject, as well as parents and homeroom and physical education teachers, completed a social validation questionnaire at the end of the program. Questionnaires employed a 7-point rating scale with higher numbers reflecting increased social validation. Questionnaires ascertained consumer satisfaction with the treatment program as well as perceived improvements in physical activity and appearance of the children. RESULTS The dependent measures were (a) the overall rate of responding per session (which was calculated by dividing the total number of revolutions per session by the total number of minutes spent exercising) and (b) the total time spent exercising per session. Figure 1 illustrates the response rates for all subjects. During baseline there was some fluctuation in response rate, with a gradual decline for 2 of the nonobese boys, Shawn and Steve. The response rate for the remaining nonobese boy, Scott, was relatively stable throughout the baseline phase. The nonobese boys responded at a mean of 71.9 revolutions per minute during baseline. For the obese boys, there was an initial increase in response rate from the first to the second session, followed by generally stable responding for Peter and Paul during baseline. The performance of the remaining obese subject, Perry, continued to accelerate until the third session, when there was a sharp decrement followed by stable responding. The obese boys responded at a mean of 59.2 revolutions per minute during baseline, which was 12.8 revolutions per minute slower than their slimmer counterparts. Upon implementation of the initial VR schedules, response rates for all subjects increased. Performance was consistently above the criterion for all boys (criterion was set at approximately 15% over each individual subject's baseline performance). The mean rate of re- 674 RAYLEEN V. DE LUCA and STEPHEN W. HOLBORN VR 115 VR 80 BASELINE 160 VR 130 VR 130 BL 140 120i1001- 80 .-2 ..... 60 BASELINE 150.1 BL VR 125 VR 11S VR 8S VR 125 I_ _ 130. 10~~~~~~~~~~ I 70 . 1!aI 15l0 r III II I t BASELINE VR8S I tm VR125 VR11S BL SHAWN VR12S _ 130t rm~~~ ' 40 co 0 VR 95 VR 70 BASELINE BL VR 100 VR 100 1401o > '- 120 100 * j so~ ~~~N 140 120 k, BASELINE VR 105 VR 80 BL VR 120 i_ VR 120 __ so . 100I 140 120t 40 so ~ BASELINE VR ~70 ~ VR 90 ~ VR 110 I BL VRI 110 _,t'.O" 1 s RO 20 2Y 10 L YR 10 SESSIONS Figure 1. Mean revolutions pedaled per minute during baseline, VR 1 (VR range, 70 to 85), VR 2 (VR range, 90 to 115), VR 3 (VR range, 100 to 130), return to baseline, and return to VR 3 phases for obese and nonobese subjects. VR REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULE sponding during the first VR subphase was 98.89 revolutions per minute for the nonobese boys and 85.51 revolutions per minute for the obese boys. The change in criterion in the second VR subphase produced an increase in response rate for all subjects. The mean rate of responding during the second VR subphase for nonobese boys was 114.2, whereas the obese boys' rate was somewhat slower at 101.2 revolutions per minute. However, unlike performance during the first VR subphase, each boy's response rate was initially slightly slower than the set criterion. Of course, falling below criterion still produced substantial reinforcement on the VR schedule, due to variability in the ratios required for reinforcement (i.e., some of the ratios fell below 80 responses per minute). There was an initial increase in performance for all boys upon implementation of the third VR subphase. One nonobese and 2 obese boys performed at or above the criterion throughout this subphase. The remaining subjects performed at approximately the criterion rate. The mean response rate for the nonobese subjects was 130.0 revolutions per minute, whereas the obese boys pedaled a mean of 117.0 revolutions per minute. Implementation of the return-to-baseline phase produced a reduction in response rate for all boys. The mean response rate of 95.3 for nonobese boys was higher than the obese boys' mean rate of 83.6 revolutions per minute. Reintroduction of the token economy produced substantial increases in all subjects' response rates. Both nonobese and obese subjects achieved their highest response rates during this subphase. The mean rate of responding during the final VR subphase was 138.7 revolutions per minute for nonobese boys, whereas the obese boys performed at the mean rate of 123.6 revolutions per minute. During the final subphase of the program, 3 nonobese and 2 obese boys consistently performed well above the criterion, and upward trends were evident. The response rate for the remaining obese child, Perry, was relatively stable (M = 98.9) throughout the phase, and he performed slightly above the criterion during the last session. 675 Figure 2 shows the total time spent riding the exercise bicyde by all subjects. (Data points are absent for Perry for eight sessions because he was absent from school.) It can be seen that during baseline there was a general decline over sessions in the duration of exercise for all subjects. Nonobese boys exercised a mean of 15.2 min per session, whereas obese boys spent slightly less time pedaling (M = 12.9 min). The implementation of a reinforcement program produced a substantial increase in the amount of time spent exercising by all subjects. Although 1 obese subject, Paul, did not exercise for the entire allotted period of time during the first session, performance of all subjects stabilized at the maximum of 30 min. All boys exercised the full 30 min during all contingency phases. Introduction of the return-to-baseline phase produced decreases in the time spent exercising for all nonobese and obese boys. Nonobese boys exercised a mean of 11.2 min per session during the returnto-baseline phase, whereas the obese children pedaled a mean of 13.3 min per session. The reintroduction ofreinforcement increased performance once again, and all subjects exercised- the maximum of 30 min per session for the duration of the program. Responses to the social validation questionnaire from the children, parents, and teachers were uniformly positive. With respect to satisfaction with the treatment procedures, the modal rating for all groups was 7 (the highest possible score on the 7-point rating scale). Ratings of improvements in physical activity and appearance were also extremely high (mode = 7). DISCUSSION The results of the present study indicated that the rate of exercise, as measured by the speed of bicyde pedaling, can be increased using a VR schedule of reinforcement. As expected, the introduction of the initial VR subphase of the changing-criterion design produced marked increases in the rate of exercise for all subjects. The outcome is an extension of De Luca and Holbom's (1990) findings that high rates of exercise were established during a ratio 676 . RAYLEEN V. DE LUCA and STEPHEN W. HOLBORN 50 S 50 40 VR 130 VR 125 II ,~~~~~~ VR 12S B. FBASELINE *VR 8S VR1llS VRI12S BL VR. 120 BL 15 S 50 VR ;* 30. 25 20 15 10 VR 125 wS I 50 40 30 25 20 . 15 10 5 VR 80 BASELINE . . . .. .4... .. . .. . _, S'' tBASELINE I 40 30 25 20 15 10 5 50 I-. BASELINE *. 4 VR. .105. . . . VR 702 I412 I L . . VR 90 VR a 2 110 1 1- VR 95 VR 100 0_##8v_ V 70 VR 120 . . * _*S 501 40 30 25 20 15 10 BL VR 115 10 5 VR 130 85 I i 40 115 1 4- BASELINE 30 25 20 VR VR 80 BASELINE 40 30 25 20 15 10 4'III II 4~ VR 110 VR 100 BL , I S * 5 0o 15 20 50 35 40 SESSIONS Figure 2. Total number of minutes spent exercising during baseline, VR I (VR range, 70 to 85), VR 2 (VR range, 90 to 115), VR 3 (VR range, 100 to 130), return to baseline, and return to VR 3 phases for obese and nonobese subjects. VR REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULE (FR) schedule of reinforcement. It is noteworthy that the highest rates achieved under VR by both obese and nonobese boys in the present study were generally greater than the most accelerated rates under the FR in the earlier De Luca and Holbom (1990) research. High rates of responding with infrequent pausing are typically produced with humans and animals on VR schedules (e.g., Lowe, 1979; Orlando & Bijou, 1960). In addition, further support is provided for the view that VR schedules can attenuate past history differences (Baron & Galizio, 1983; Kaufman, Baron, & Kopp, 1966). In particular, the obese subjects' histories of reduced rates of responding were eventually overcome by successively increasing levels of the VR schedule. For 2 of the obese subjects (Peter and Paul), the final levels of exercise approximated those of the nonobese boys. Perry's final VR performance was lower, but he was absent for much of the training. Another contributing factor to the higher rates may have been use of a changing-criterion design. In the present study, the rate of exercise generally improved in increments to match or exceed the criterion specified. An exception to this occurred with 1 obese and 1 nonobese boy who did not meet the criterion during the third subphase. In many studies, not meeting the criterion would have negated reinforcement (Kazdin, 1982); however, in the present study, because of the variable nature of the schedule it resulted only in reduced amounts of reinforcement. The 2 children's behavior came under control of the criterion in the following phase, and their exercise behavior accelerated as they attempted to "catch up" in points to their peers. The results also corroborate De Luca and Holbom's (1985, 1990) findings that exercise duration can be increased using behavioral principles of reinforcement with children. The introduction of a token economy produced increases in duration of exercise to the maximum 30 min. Control was evident in the children's duration of bicyde pedaling. When the children received reinforcement for biking, they continued for the maximum allotted time; when they did not receive reinforcement, their pedaling rapidly decreased. When reinforcement 677 was withdrawn and the bicyde's bell and light no longer signaled points, the boys reduced their time spent pedaling and complained about no longer being able to collect points. Turning to indices of social validity, the questionnaire data for the children, their parents, and their teachers uniformly indicated maximum or dose to maximum ratings of satisfaction with both treatment procedures and outcome. Also, there were other anecdotal indicators of consumer satisfaction that are equally compelling. For example, in relation to satisfaction with treatment procedures, on a number of occasions boys in the program asked if their friends could participate. Many times when the 30 min were over, the children asked if they could bicyde for a longer time to "get more points." Parents of all of the boys reported that their sons had spoken positively about the program, with one parent of an obese boy stating "that's all he talked about for weeks." Each of the obese boys convinced their parents to purchase a new bicyde for him during the course of the study. The boys daimed that although each had ridden bicydes in the past, they really had not cared much for biking. In relation to satisfaction with treatment outcome, the convergence of a variety of anecdotal observations proved persuasive of positive effect. Every subject participated in the school's track and field events. The nonobese boys participated in running events, and the obese boys participated in ball throwing, long jumping, and high jumping. Two of the obese boys received ribbons of achievement for the first time in these events. Although all of the nonobese boys received ribbons at the track and field meet, 2 of them (Shawn and Steve) went on to compete in the 200-m and 400-m runs in the citywide track and field meet. Shawn won an award for his division. Shawn's mother reported that she felt her son's participation in the biking program improved his stamina, enabling him to compete in a larger meet for the first time. Reduced girth measurements were most noticeable for Peter. He was excited that he could now wear his stepfather's pants (Size 32) rather than the Size 36 he had previously wom. The vice- 678 RAYLEEN V. DE LUCA and STEPHEN W. HOLBORN principal ofthe school commented that "Peter looks like a new boy. He looks terrific." Peter's mother reported that when he went for a physical examination prior to going to camp, the doctor complimented Peter on his improved appearance and fitness. Playing soccer and swimming became frequent activities for Peter. All parents were very supportive of the program and felt their sons had benefited from it. The parents of 1 obese boy stated that they had been initially hesitant about the program, but were "very thrilled" with the outcome and their son's "changed attitude" about participating in physical activity. Peter's mother asked if her younger son could also be involved in the program. Teachers stated that the program was very beneficial for all students. However, changes in physical activity were noticed particularly for the obese boys, who they felt had particularly benefited from the program. A number of interesting areas remain for future research. Primary among these should be the design of experiments to assess and program for generalization of trained exercise behaviors to the natural environment. Because there are more overweight girls than boys (Manitoba Department of Education, 1978), it will be important to indude obese girls, as well as boys, in future research. Although the results of the present study are promising, further research on curtailment of obesity at an early age is crucial, if enduring life-style changes are to prevent obese youngsters from becoming obese adults. REFERENCES Aristimuno, G. G., Foster, T. A., Voors, A. W., Srinivasan, S. R., & Berenson, G. S. (1984). Influence of persistent obesity in children on cardiovascular risk factors: The Bogglusa Heart Study. Circulation, 69, 895-904. Baron, A., & Galizio, M. (1983). Instructional control of human operant behavior. Psychological Record, 33, 495520. Brownell, K. D. (1984). The psychology and physiology of obesity: Implication for screening and treatment.Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 4, 406-414. Bullen, B. A., Reed, R. B., & Mayer, J. (1964). Physical activity of obese and non-obese and adolescent girls appraised by motion picture sampling. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 14, 211-233. Canada. Department of Health and Welfare. (1984). Standardized tests of fitness. Ottawa, Ontario: Fitness and Amateur Sport. Cautela,J. R. (1977). Behavior analysisforms for clinical intervention. Champaign, IL: Research Press. Cohen, E. A., Gelfand, D. M., Dodd, D. K., Jensen, J., & Turner, C. (1980). Self-control practices associated with weight loss maintenance in children and adolescents. Behavior Therapy, 11, 26-37. De Luca, R. V., & Holborn, S. W. (1985). Effects of a fixed-interval schedule of token reinforcement on exercise with obese and non-obese boys. Psychological Record, 35, 525-533. De Luca, R. V., & Holborn, S. W. (1990). Effects of fixedinterval and fixed-ratio schedules of token reinforcement on exercise with obese and non-obese boys. Psychological Record, 40, 67-82. Demirjian, A. (1980). Anthropometry report: Height, weight and body dimensions. A report from Nutrition Canada. Ottawa, Ontario: Department of Health and Welfare. Epstein, L. H., & Wing, R. R. (1987). Behavioral treatment of childhood obesity. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 331-342. Epstein, L. N., Wing, R. R., Koeske, R., & Valoski, A. (1987). Long-term effects of family-based treatment of childhood obesity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 91-95. Hartmann, D. D., & Hall, R. V. (1976). The changing criterion design. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 9, 527-532. Israel, A. C., & Stolmaker, L. (1980). Behavioral treatment of obesity in children and adolescents. In M. Hersen, R. M. Eisler, & P. M. Miller (Eds.), Progress in behavior modification (Vol. 10, pp. 82-109). New York: Academic Press. Johnson, M. L., Burke, B. S., & Mayer, J. (1956). Prevalence and incidence of obesity in a cross-section of elementary and secondary school children. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 4, 231-238. Kaufman, A., Baron, A., & Kopp, R. E. (1966). Some effects of instructions on human operant behavior. Psychonomic Monograph Supplements, 1, 243-250. Kazdin, A. E. (1982). Single-case research designs: Methods for clinical and applied settings. New York: Oxford University Press. Lowe, C. F. (1979). Determinants of human operant behavior. In M. D. Zeiler & P. Harzem (Eds.), Advances in analysis of behavior: Reinforcement and the organization of behavior (Vol. 1, pp. 159-192). Chichester, England: Wiley. Manitoba Department of Education. (1978). Manitoba schoolsphysicalfitness survey, 1976-1977. Winnipeg, Manitoba: Author. Mann, G. V. (1974). The influence of obesity on health. New England Journal of Medicine, 291, 178-185. Mayer, J. (1968). Overweight: Causes, cost and control. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Mayer, J. (1970). Some aspects of the problem of regu- VR REINFORCEMENT SCHEDULE lating food intake and obesity. International Psychiatry Clinics, 7, 225-234. Mobbs, J. (1970). Childhood obesity. InternationalJournal of Nursing Studies, 7, 3-18. Orlando, R., & Bijou, S. W. (1960). Single and multiple schedules of reinforcement in developmentally retarded children. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 3, 339-348. Rony, H. R. (1940). Obesity and leaness. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger. Seltzer, C. C., & Mayer, J. (1965). A simple criterion of obesity. Postgraduate Medicine, 38, 101-107. 679 Stefanik, P. A., Heald, F. P., & Mayer, J. (1959). Caloric intake in relation to energy output of obese and nonobese adolescent boys. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 7, 55-62. ReceivedJuly 9, 1990 Initial editorial decision September 13, 1990 Revisions received December 13, 1990; April 29, 1991; July 21, 1991 Final acceptance August 23, 1991 Action Editor, Charles R. Greenwood