A new model of population based primary health care for Ontario

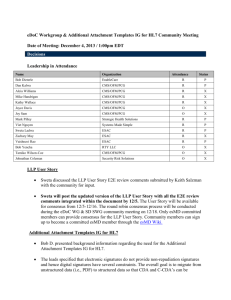

advertisement